The Movies We Loved From Sundance This Year

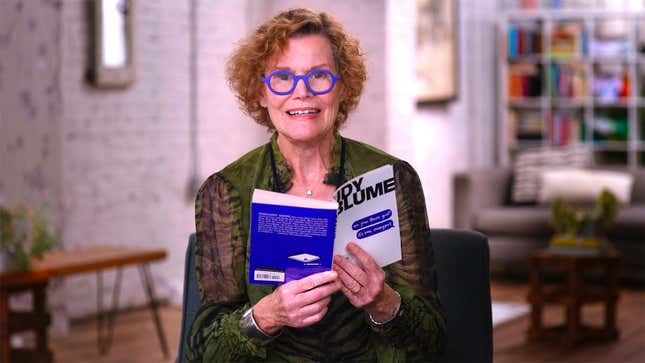

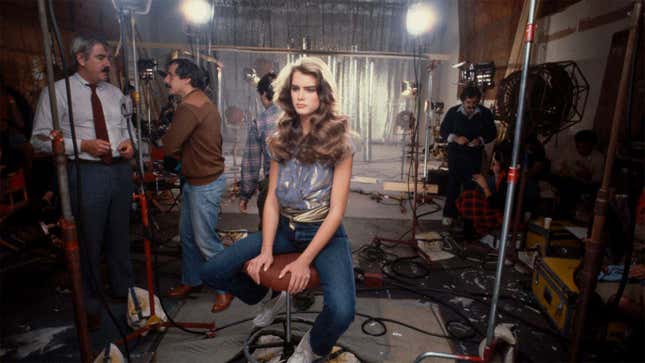

Judy Blume, Little Richard, and trans sex workers buoyed a particularly strong lineup, alongside films like Infinity Pool and Eileen.

EntertainmentMovies-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-