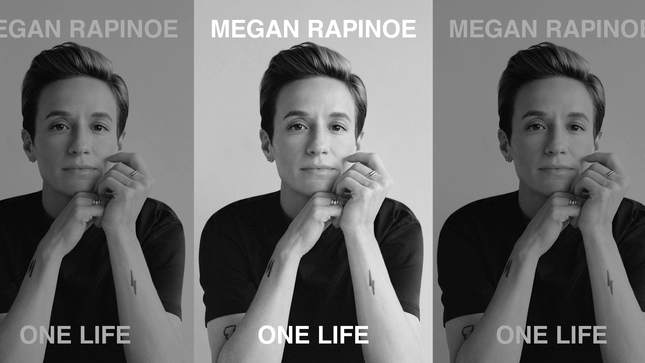

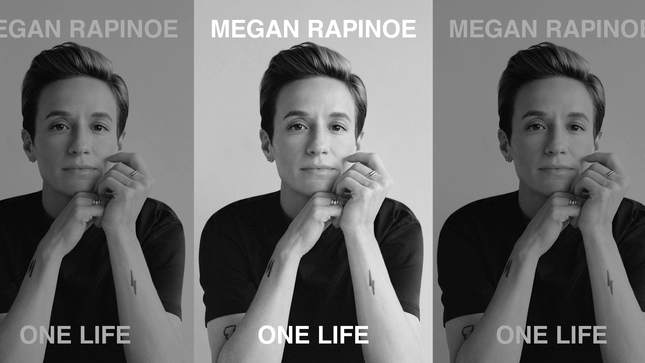

Megan Rapinoe's Long Fight for Equality

In Depth

Before Megan Rapinoe was a World Cup-winning, gold medal-earning, equal pay-defending, marriage equality-advocating superstar who also happened to play soccer, she was a largely unknown athlete from Redding, California, trying to make heads or tails of her future and her own sexuality. Rapinoe, who played soccer from childhood with her twin sister Rachael, was thrust into the national spotlight in 2016, when she knelt during the playing of the national anthem in solidarity with Colin Kaepernick—who, unlike Rapinoe, never worked as a professional athlete again. Rapinoe’s memoir, One Life, is not so much the story of Rapinoe’s journey from birth to soccer stardom but the story of how she came to take a knee, tracing a political awakening that began long before that career- and league-changing game.

Long before the US Soccer Federation banned kneeling in response to its biggest rising star taking action, Megan Rapinoe was a young athlete in California, growing up in a town where local youth soccer programs for girls weren’t as established as they are now. “In my entire history of playing, I have never dominated a team like I did that team of small boys in the early 1990s,” she writes of the time she spent playing on her local under-8 boys’ team, which she and her sister were invited to join before her father eventually started a girls’ team. Tracing her early involvement in the sport, Megan also provides a brief history of the somewhat stop-and-start beginnings of professional women’s soccer in the United States. The Women’s United Soccer Association grew out of the excitement over the 1999 FIFA Women’s World Cup-winning team, launching in 2001, but WUSA folded after three seasons. Rapinoe, who had already made appearances with the national team, would start her professional career in Chicago in the next iteration of professional women’s soccer, the Women’s Professional Soccer league, where she was paid $32,000 a year, with a second salary for playing on the national team. This league would also fold.

But the meat of the book is Rapinoe’s journey from simply a (very good) soccer player to a woman with a platform so strong that President-elect Joe Biden and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have both taken the time to speak with her. As she tells it, Megan’s political awakening began with her brother, Brian, who spent most of Rapinoe’s adolescence struggling with addiction and cycling in and out of the prison system. Brian’s experiences shaped Megan’s understanding of fairness, particularly as it related to criminal justice. She writes:

There is another truth about drug addicts, and by extension those who serve time in prison: While, as human beings, they are valued by society at nothing their, symbolic value to the system is huge. For “us” to be “good,” “they” must be “bad”—and not just bad, but irredeemably so. It’s classic divide and rule and makes rehabilitation almost impossible. It also ensures that those entering the system are out beyond the reach of our common humanity.

Rapinoe’s consciousness was further shaped by the moment in college when, for the first time in her life, she realized she was gay. Megan’s very public advocacy for same-sex marriage rights often put her at odds with her teammates.“I looked down the aircraft at all of the other gay players, most of them older than me,” she writes. “Why am I not out? Why are we all not out?” It was this fight that would prepare her for her most public match yet: Rapinoe v. United States Soccer Federation.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-