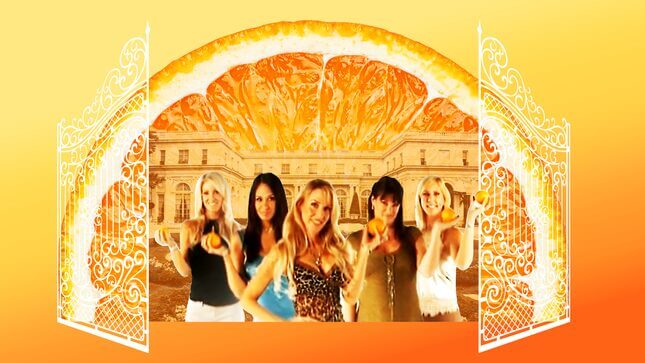

Looking Back at the Debut of Real Housewives of Orange County, the Show That Started It All

In DepthIn Depth

Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Screenshot via YouTube, Shutterstock)

The Real Housewives of Orange County wasn’t supposed to end up as it did. It was supposed to be a quaint little docu-series called Behind the Gates, which creator Scott Dunlop pitched to networks as a look into the dinner-party conversations he’d had with rich “housewives” in the affluent Orange County gated suburb of Coto De Caza, dubbed “Coto” by its residents.

Yet after 1,545 episodes, 84 seasons, and 11 spin-offs—not including the international variants—The Real Housewives is inarguably the most iconic reality television IP in any network’s history. It has spawned roadshows, podcasts, websites, and social media frenzies. There are conventions catering to its sprawling mass, or there were before the pandemic, anyway. Its stars, the housewives themselves (who are not always wives), have shaped the language of memes online for a decade, birthing new screencaps and GIFs and catchphrases and retorts at an alarming rate. Most important, however, is how the franchise has shaped the business of reality TV with the model that The Real Housewives perfected: a cast of zany socialites plugged into recurring confessionals and trailed by glam squads, personal photographers, and at least a half-dozen controversies. Throw a rock in any direction and it’s bound to hit a look-a-like.

What began as a peek into the world of the “real” Desperate Housewives of an exclusive California suburb ultimately evolved into a premiere television destination, where personalities are built, packaged, and shipped out en masse. The vacuous cast members of that first season of The Real Housewives of Orange County were primarily concerned with the sort of cars their neighbors recently leased and whether their nemesis in the school pick-up line had a real Rolex or a fake. But the devastating recession in 2008 collapsed that universe

and transformed the franchise into the juggernaut it is today. The show ultimately became less about simply having wealth, but the cutthroat and increasingly dramatic pursuit of it—the glitz and the grift that defines our era.

Beat for beat, the arc of The Real Housewives of Orange County charts the sudden death of an American dream and its zombie-like rebirth. No longer did the aspiring suburban rich need to while away the hours of their life in a nondescript office somewhere in San Bernadino or suffer with the children while their spouses promised better lives in the future. With the expansion of The Real Housewives into cities across the country, why not start a purse line, rent a McMansion, and try that elusive luck on television.

Behind the Gates was picked up in 2005 by Bravo, then just a minor player in the cable wars boasting innumerable failed reality television attempts and two breakout hits, Project Runway and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Fun and frothy, Bravo’s haphazard lineup was notable for catering to an oft-hinted-at gay audience, or at least, pop culture savants who may or may not have been gay. Former Bravo exec and current Real Housewives executive producer Andy Cohen’s rise into the pantheon of extremely famous homosexuals later in the 2010s only confirms this, as he was so clearly the architect of the network’s modern ubiquity, with his name plastered front and center on some of NBC Universal Comcast’s most profitable business ventures.

As Scott Dunlop later told the Guardian, execs at Bravo reworked Behind the Gates into a show more akin to Desperate Housewives, then a ratings hit and a pop-cultural obsession in a country consumed with wealth amid the economic boom that preceded the 2008 bust. Fox’s classically melodramatic The O.C, about disaffected Southern California teens, was yet another facet of this national fixation. Across America, plots of land were being bulldozed for suburban tract housing connected to swanky retail outlets by cars that were bigger, fancier, and more gas-guzzling than ever. The show it soon became, The Real Housewives of Orange County, launched on March 21, 2006, to near national fascination. Slate columnist Troy Patterson wrote at the time: “Here is a craftily presented slice of America that makes room for guns, silicone, status anxiety, and sibling rivalry,” noting: “What makes the show something better than a guilty pleasure is the way that, after introducing its subjects as borderline-reprehensible cartoons, it allows them flickers of self-awareness or shows them trying their damnedest to be terrific parents.”

In Washington Post critic Tom Shales’s review of the premiere episode, he wrote: “The people of Orange County as seen in this documentary look as though they couldn’t care less, that the whole thing is a kind of kick for them, and maybe an excuse to have parties.” The cast’s carefree whiteness and opulent display of wealth and frivolity made for a “persistently diverting journey: that would give “sociologists and anthropologists of the future” enough material to properly understand the ‘trash heap’ of a decade known now as the aughts.”

What’s shocking to the modern The Real Housewives fan, revisiting its first season, is how utterly devoid of drama it is. There are no catfights or thrown wine glasses or even glitzy overseas vacations where one cast member inevitably has a national news-making nervous breakdown. It was told as vignettes of different women’s lives as they juggled divorce, marriage, motherhood, and partying; the original cast included Kimberly Bryant, Jo De La Rosa, Lauri Waring, Jeana Keough, and the O.G. of the OC, Vicki Gunvalson.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-