Is Cheerleading a Prison or Is It Freedom?

Author and podcast creator Sarah Hepola talks candidly about the complicated legacy of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders.

In DepthIn Depth

In the lead up to the Super Bowl each year, the internet is inexplicably deluged with stories covering every nook and cranny of the amped-up, cleavaged-up, and sometimes fucked-up world of NFL cheerleading. Reporters tend to cover cheerleaders in two disparate lanes: eagerly fawning over the spectacle of the dancers and “trailblazers” without a critical eye in sight, or ripping to shreds the teams predominantly comprised of women over their participation in a job that many find to be sexist and downright offensive.

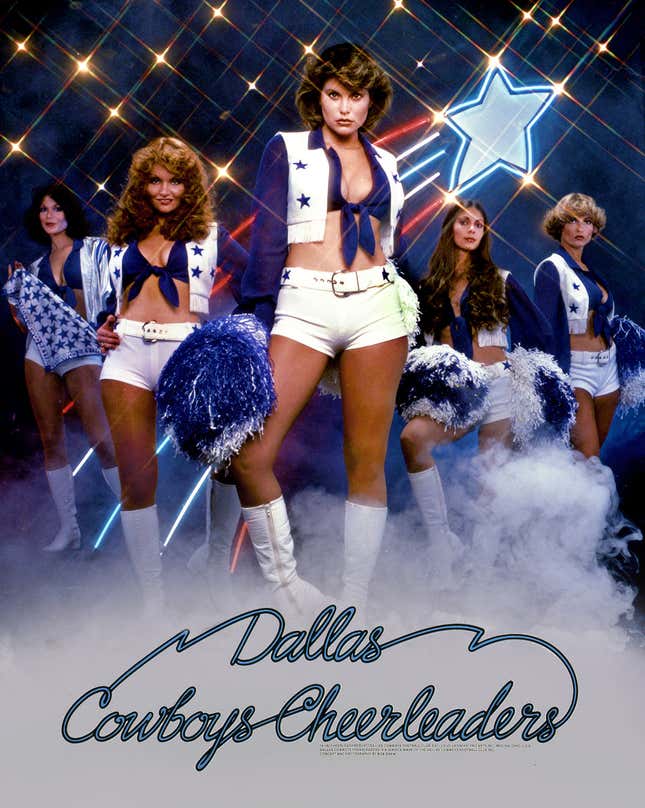

Sarah Hepola, who finds herself nestled right in the middle of these two opposing poles, is not one of those reporters. The author of the memoir Blackout and writer at large at Texas Monthly (and Jezebel regular) knows that the truth at the heart of NFL cheerleading is a duality as beautiful and glamorous as it is complicated and, at times, dangerous. Now, nearly four decades after she first fell in love with the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders on posters plastered in 7-Elevens and dance studios, Hepola has chronicled their waning legacy—both fraught and understated in its glory—in a new podcast called America’s Girls.

While Hepola’s adoration of Texas’s bombshells was difficult if not controversial to sustain throughout continued NFL scandals, her dogged pursuit of amplifying the women’s voices and giving them the same agency that was stripped away by the Cowboys has proven to be a tear-jerking journalistic venture. Atop unsteady ground that may swallow the very idea of NFL cheerleaders whole, Hepola enshrines the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders with grit and honesty. As she puts it, “To let yourself be heard, instead of just seen, when being seen is what you were always trained for, is really an amazing thing.”

Hepola and I caught up over the phone last week to talk about the massive culture impact of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders (the DCC) and their complicated legacy today. Our conversation has been edited for clarity:

Jezebel: I loved hearing about the origins of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. They were trained dancers at heart. But, as you smartly point out, dance is inherently sexual, and you mention that many cultures use dance as a celebration of their heritage. Do you think that America just doesn’t appreciate dance in a major cultural way?

Hepola: I thought that was such an important point, because you’ll see these critiques of the DCC claiming it’s all just “bump and grind.” Sure, there’s an erotic force that’s moving through the body, and you could say more coarsely that it simulates sex. But you have to remember that dancing is considered dangerous in highly religious places like Dallas, Texas for that very reason. When I was growing up, Baylor University, which is a Baptist university, did not allow dancing on that campus until 1996. There’s this big Baptist stronghold in Dallas, and a lot of the Baptists still don’t dance. That highly religious streak in American culture, which runs counterpoint to a really hedonistic and libidinal streak, shows up here in the middle of the story about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders.

The public tends to have really strong opinions about cheerleaders, but when it comes down to it, they can’t name a single one. Did you find this to be the case with the DCC?

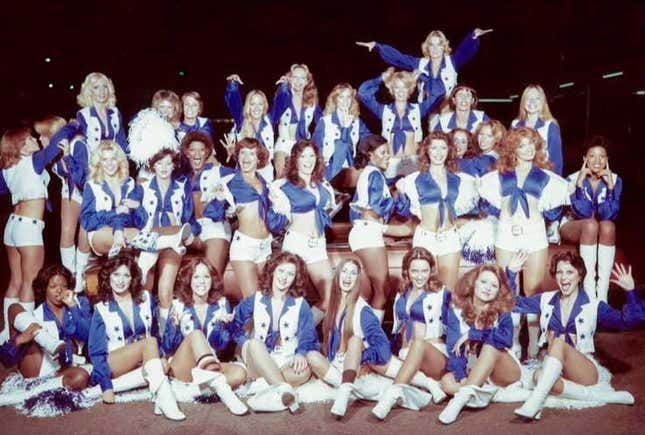

Even I couldn’t have told you their names. They are so often used as decoration, but are discouraged from speaking to the media. The result is that you don’t get any kind of personality—just a vague, anonymous beauty because of that uniform. Everyone looks the same, which makes them unidentifiable.

It’s not unlike the Playboy Bunnies in that way. Aside from racial diversity, they all just blend together.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-