Noah Levine, the influential punk rock Buddhist teacher whose meditation society, Against the Stream, collapsed after he was accused of sexual misconduct, never spoke to me for two stories I wrote about the allegations against him, despite my best efforts to contact him. But he did sit down this summer with Los Angeles magazine, for an interview published in July. In it, he indicated that the accusations against him were an outgrowth of the “hysteria” of the MeToo movement.

“This is like a cultural hysteria that’s happening that I’m caught up in,” he told journalist Sean Elder, arguing that the allegations were nothing more than a cleverly-marketed coup. He told Elder that JoAnna Hardy, the guiding teacher at Against the Stream always had ambitions to oust him. Hardy, he claimed, wanted to “get rid of the white guy… She got the support of the rest of the teachers to do it, you know, because nobody’s going to say no to the angry black woman in charge.”

It was a typically brash performance for Levine, in a year full of them: He’s refused to stop teaching dharma classes, though he was disempowered in February by famed Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield of the Spirit Rock Meditation Center, who’d authorized him as a teacher years ago and whose support he’d always clearly valued. And at the same time that he was accused of harassing several women and raping an ex-girlfriend—allegations outlined in a report produced for Against the Stream —Levine was also at the start of an ugly and ultimately very public business divorce, including dueling civil lawsuits. Those disputes ultimately severed in half Refuge Recovery, the Buddhist addiction recovery community that he played an integral part in for years.

Levine dramatically read aloud the letter withdrawing his teaching certification during a meditation class he was leading in Santa Monica, broadcasting the recitation live on Facebook.

“Obviously I will continue to teach,” he said, mid-reading. “I feel really clear that teaching is not my job, but my calling.”

Despite his grandiose declarations of outsiderdom, however, just a few short months later, Levine has more or less bounced back from the accusations against him. He’s re-formed a version of his addiction recovery community with his remaining supporters, who are working hard to characterize the people on the other side of the legal dispute as a renegade “breakaway group,” as a recent mass email put it. After his break, Levine formed a group now called Refuge Recovery World Services, while the former members of the Refuge Recovery board who sued him formed Recovery Dharma, a new nonprofit entity. Levine is still teaching meditation classes and leading spiritually focused retreats. In June, none other than Ben Affleck weighed in to support him during the civil lawsuits.

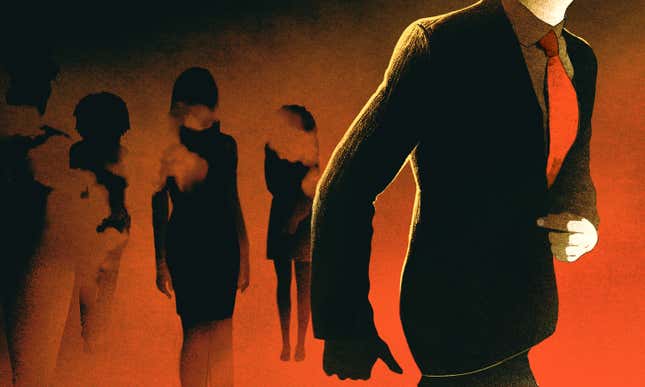

In other words, Levine is speeding back towards his previous significance at a tidy clip, even as his misconduct scandal roiled the communities around him and created deep, permanent consequences. Though the details of what happened are highly specific to the Buddhist community, the takeaways are, in a sense, universal to this cultural moment—two years after the first MeToo allegation, the aftermath looks like a litany of shamed men attempting to make their comebacks from rape and sexual misconduct accusations.

Like Levine, many of these cancelled men are supported by their communities, or some portion thereof. Where it was once unclear who, if any, of the accused men would bounce back—which stories would prove too grotesque a mark from which to rebound, and which would be looked upon as no more than a blip, now it seems a lot more clear: in some ways, as Tracy Clark-Flory wrote recently, MeToo is showing signs of winding down. Despite much hand-wringing about the pernicious effects of “cancel culture,” permanent cancellations look vanishingly rare.

But what exactly happens after someone decides that he’s through being punished for his bad behavior—and it’s always downplayed as “bad behavior” —and tries to resume his place? In an era where the collective memory seems radically shortened by a chaotic news cycle and the sheer weight of multiple competing emergencies, have we been able to create longterm structural changes? And as the canceled men all line themselves up again for ill-deserved, ill-defined, poorly-earned shots at redemption, how does a community around them remember the accusations against them while still trying to move forward?

MeToo as a movement has always been theoretical—a group of men who, with few exceptions, were accused of crimes to the fabric of society. With the exception of a few major players—Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Mario Batali—most men accused of sexual misconduct during MeToo weren’t criminally charged. There’s no procedure or natural punishment for this kind of social crime (and sometimes, no agreement about whether some of these acts are crimes at all). The only real barrier to return is how their community and the public responds. Any repercussions are reliant on something we often take for granted: that when someone does something terrible, shame is assumed to be the result, both on the part of the ousted person and the systems that let them persist. So here we find ourselves, two years into this precedent-setting movement—but without shame, did the movement even do anything?

The next stage of the movement is testing systems of community accountability versus the sheer weight of brazen, undisguised defiance. And it’s not at all clear, not yet, which holds more sway.

The afternoon when Levine read the letter disempowering him from teaching aloud to his new meditation group, he paused. He held the letter, seemingly lost in a moment of self-reflection.

“I know this is a little bit dramatic,” he said finally, to laughter from the room. He then tore up the authorization certificate, drawing murmurs and some applause. Levine also declared that from here on out, he was no longer supported by the “insight establishment,” as he put it, and that was just fine with him.

There are a few instances, of course, where shamelessness isn’t enough: Take Mark Halperin, who was a middling political commentator before he

was accused by multiple women of harassment, including throwing

one woman against a window before trying to kiss her and rubbing his clothed erection against several others.

Halperin certainly seems to think his perspective is invaluable and his return warranted, but as it stands, he’s in the midst of a rather rocky redemption tour, trying to drum up press for a book no one seems to want to read and a newsletter that sounds punishingly dull. The Daily Beast recently reported that Halperin vaguely threatened MSNBC’s network chief Phil Griffin when, earlier this year, Griffin nixed the idea of Halperin collaborating with the hosts of Morning Joe. The threats—another concrete expression of shamelessness—didn’t really work; an infuriated Griffin just refused to ever get on the phone with Halperin again, the Beast reported.

In other cases, though, personal and institutional shamelessness has gone quite swimmingly: star political reporter Glenn Thrush of the New York Times was recently re-installed at a job that looks a lot like his old one— covering D.C. politics and the 2020 elections —after being reassigned to a beat covering, of all things, the social safety net in 2017, following multiple harassment allegations. The Times hasn’t even covered the optics of his reassignment beyond a glowing press release. While there’s been some outcry on Twitter, much of it around the fact that he got to keep his book advance after being fired from writing it, while his co-author Maggie Haberman ultimately had to return hers, Thrush and the newspaper have done just fine by ignoring it altogether.

Or take Louis CK: while his career still hasn’t bounced entirely back from the revelations that he masturbated in front of non-consenting women and lied about it for years, he’s been steadily touring again, both in Europe and in smaller venues across the United States. A review of a show in North Texas from this summer approvingly noted that he was “not directly asking for forgiveness” during the show, instead making jokes about what he did. The writer of the review, Ryan J. Rusak, then clumsily tried to parlay CK into a broader point about the apparent need to admit abusive men back into society.

“Enough men have done enough vile, abusive things that fall short of outright sexual crime that we need a way to figure out if they can seek, and gain, redemption and continue to contribute to society,” Rusak wrote. “Each case is different. In a world that increasingly wants us to slash through nuance with bright lines, that answer may not satisfy. But like Louie’s show, it’s honest and direct.”

That argument—that a lot of men do “vile, abusive things,” so we’ll necessarily have to find room for them all again—is a little staggering in its laziness, its indifference towards victims, the crudeness of its calculations: There are too many of them not to grant some form of redemption. But it’s revealing too: shamelessness works when it’s not limited to perpetrators alone, but when an audience possesses it too, when they want to forget what you did as badly as you do. That’s been true long before CK: Mel Gibson, who assuredly did not deserve a comeback, has, at this point, been back in the public eye so long that most stories about his new projects don’t even bother to mention the accusations of domestic violence against him, nor his anti-Semitic remarks, racism and homophobia.

And when shamelessness plays out successfully among the bigger players, the smaller ones copy it too. Alex Boyko is a tattoo artist I reported on in January 2018 as the epicenter of the tattoo world’s MeToo reckoning. Boyko was accused by dozens of women on social media of sexually inappropriate behavior, including assault, both during tattoo appointments and in his personal life. (I have never personally reported another story with quite so many accusers.)

Boyko’s response to the many allegations against him was twofold: just after my story went up, he posted a series of Instagram photos of women he’d tattooed, photographed topless. Then he sued, for defamation, some of the tattoo artists who’d repeated the allegations against him. The suit was unsuccessful: court records show that the suit was dismissed earlier this year and a judge awarded compensation to two of the artists Boyko sued. (Boyko appears to be trying to appeal the judgment.)

Scrolling through his Instagram, it’s hard to know anything happened at all.

Though Boyko’s quest for revenge seems to have come up empty, the shameless route has helped his career rebound. He’s never made a public apology or tried to publicly reckon with the sheer number of women who accused him. He turned off comments on his Instagram and continues taking bookings, by direct message only, and apparently continues to tattoo at both a private studio in Detroit and at guest bookings in New York and Los Angeles, according to his Instagram stories. While his business may have suffered — there’s no real way to tell — publicly, everything seems to have returned to normal. Scrolling through his Instagram, it’s hard to know anything happened at all.

In the end, the problem here is one of incentives: there’s no reason, not really, for most of these men to honestly engage with the accusations against them, to sincerely try to be different or better. There’s no money in something as intangible as a moral awakening or a strengthened sense of personal ethics, there’s no guaranteed return to fame, and—because this is how consequences work—many people will continue to be angry and disgusted with them just the same.

So the better path, for so many, is to forge ahead, pretending—to the public, on social media, and to themselves—that a brief public hiatus is itself a form of penance and redemption. A number of these men have turned actively towards defiance and deflection too, an insinuation that in being accused of something they were the ones who’d been wronged. It’s a handy way to turn the tables on their accusers and shore up support among their base, however small or shaky it might be. See, for instance, Ryan Adams’ cliche-addled Instagram comeback back in July, a tidy six months after he was accused of sexually exploiting a 14-year-old girl and mistreating numerous women he’d collaborated with. ““I have a lot to say,” he wrote, in poem form, for some reason. “I am going to. Soon. Because the truth matters. It’s what matters most. I know who I am. What I am. It’s time people know. Past time.”

These days, Adams posts photos of his cat, his lunch, repulsive selfies, sentimental thoughts about the 9/11 anniversary—anything and everything to bury the accusations against him under a thick layer of internet detritus. Instagram has proven to be an especially popular medium for the shamed man, given how easy it is to give off an air of casual, ebullient normalcy, and how simple it is to turn off comments to make sure nobody punctures the narrative.

In the end, all these millions of versions of redemption begin to look more or less the same: men deciding of their own volition that they’ve been hurt personally enough, and that all this suffering is painful or unpleasant, or, more importantly, a real drain on their bank accounts.

Shamelessness, meanwhile, sells. Former Senator Al Franken is planning a brief run of public talks this fall, two years after he resigned and just a few short months after a wildly sympathetic New Yorker story that sought to make him into the victim of his own sexual misconduct scandal. (He was also further rewarded just this week with a weekly talk radio show.) According to the event description of his Portland, Oregon show, per Willamette Week, Franken promises to offer a behind-the-scenes look at the U.S. Senate, to “cut through the conventional wisdom and tell you how it really is.” An offer from a man who’s unable to speak truthfully or realistically about what led to his downfall to tell you “how it really is”—that is, in the end, the essence of shamelessness.

In the case of Noah Levine, the shamed-and-returned Buddhist leader, though, it’s also true that the religious community who cut ties with him is making their own way, free from his scandals. I spoke recently with Jean Tuller and Jessica Lipman, both of whom were previously involved in the nonprofit Refuge Recovery. Tuller was the executive director of the board, and Levine was her teacher in Buddhism for many years. Tuller and Lipman are both now part of Recovery Dharma, the new nonprofit that Levine and his allies have referred to as a “breakaway” group. They’re leaving the Refuge Recovery name with Levine, the addiction recovery manual he’s credited with authoring, and they’re mostly declining to respond to the volley of emails his new organization has sent out. When we spoke, Tuller politely declined to discuss, in much detail, the sexual abuse allegations themselves, the lawsuit, Levine’s moving forward or the ugly things he’s said.

“We issued a joint statement that we all worked hard to craft that said that we wish each other well and we’re aware of the divisiveness this has caused within the community,” Tuller told me. “I have an understanding of what that statement means and I’m going to stay by that.” In her world, she added, “There’s some celebration going on right now.” In my view, she seemed to be referring to people who were finally freed from both the ugliness of a lengthy bout of civil litigation and who’d been able to publicly cut ties with a person they viewed as ethically compromised.

“There’s a wonderful collaborative community spirit that’s unfolding every day,” Tuller said.

It occurred to me, as we talked, that the cancelled men, as they make their effortful returns, don’t talk much about community. Their focus is so firmly on themselves, their feelings, their egos, their rightful place in society, that broader communities—the collectives of people they’ve harmed, directly and indirectly—seem to get lost. It’s almost as though it wasn’t about those people to begin with; that shamelessness, in the end, is a cover for the selfishness it barely masked all along.