The New Yorker Seriously Mischaracterized the Story of One of Al Franken's Accusers

Latest

This week, the New Yorker ran a long piece by Jane Mayer re-examining the sexual harassment allegations against Al Franken, a piece which minimized the accusations themselves while giving Franken ample space to defend himself. While the piece contained some unflattering new revelations about Leeann Tweeden’s story, the conservative radio host who made the first public accusation, it was notably weaker in dealing with the other women who made accusations of groping, harassment and unwanted kissing.

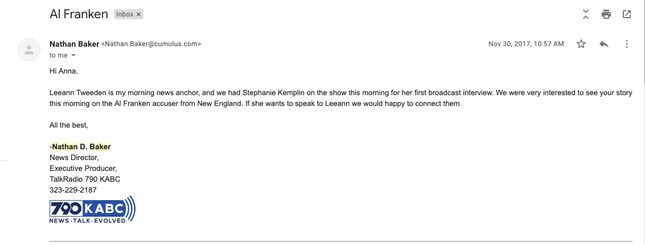

Unfortunately, Mayer and the New Yorker also seriously mischaracterized the story of one of those accusers, whom Jezebel previously reported on. The accuser provided Jezebel an account of her interactions with Mayer and a New Yorker fact-checker, which she said left her feeling as though the overall intent of the story was to discredit and mischaracterize her and how she behaved in the aftermath of the incident. The publication also made statements we can prove are demonstrably misleading; failed to contact us for comment at any point prior to publication; and have, to date, declined to make any corrections.

On November 30, 2017, we ran a story about an anonymous former New England elected official who said that in 2006 Franken tried to give her a “wet, open-mouthed kiss” onstage. Franken was then a host at Air America, and announced his Senate run a short time later. The woman had agreed to appear at a live taping of his show and sit for an interview in front of an audience. She said the attempted kiss, which she turned her head to avoid, made her feel “stunned and incredulous. I felt demeaned. I felt put in my place.”

In isolation, the incident looks bizarre, clumsy, but possibly innocuous; combined with the accounts of the five other women who’d come forward by then—who became seven in the end—it looked like an indication that Franken had serious issues with maintaining appropriate physical boundaries with women. (There are no reports that he kissed any men, palmed their buttocks while posing for photos, or jokingly pretended to grope their chests in photos while they slept. He was only “clumsy” in one direction, it seems.)

The woman we spoke to, however, was adamant at the time that she wasn’t looking for Franken to resign, and admired his politics. Her sister and a family friend confirmed they’d both been told about the incident at the time it occurred. All three of them said they respected Franken and merely wanted him to take ownership of his behavior.

“I want him to take personal responsibility for his actions, learn from this, not repeat the behavior,” the woman told us at the time, “and go forward with respect in all his interactions with women.”

Jezebel granted the woman anonymity because she was describing an incident of sexual harassment, and explained that she’d been reluctant to come forward before because she didn’t want her name and hard-won reputation as a former elected official to become linked to a man’s bad behavior. Jezebel, like every reputable news outlet, doesn’t identify victims of sexual misconduct without their permission. (This will, sadly, become important in a moment.) Our piece was vetted by our lawyer, Lynn Oberlander, who was, ironically, previously the general counsel at the New Yorker.

Jezebel contacted Franken and his staff for comment; I provided the woman’s name to them so they could more easily remember the event. I then spoke on the phone with two members of Franken’s communications team. One of them, Ed Shelleby, responded, “That’s all very interesting, thank you,” when I described the incident, then never responded to a single email ever again.

Mayer doesn’t dispute that the kiss happened. When she was reporting her piece for the New Yorker, in fact, she located a local reporter who’d been in the audience when the kiss occurred, and said he witnessed it. (The woman had told me she didn’t think anybody had seen it happen, calling it “insidious.”) Mayer writes:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-