We Are Losing Black Girls

Black girls not only edge out their white counterparts, but also Black boys, with soaring rates of suicide—partly because they have been ignored for so long.

In Depth

“Something is happening among our Black girls,” Dr. Arielle Sheftall said last fall.

Sheftall, lead investigator of the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, made it her mission to dissect the suicidal behavior of Black youth, and in a 2021 study, she unearthed something important: The rate of suicide among Black girls ages 15 to 17 was increasing at twice the rate of Black boys every year between 2003 and 2017, though more Black boys are dying by suicide than Black girls. This was “quite concerning,” Sheftall told Columbus news station 10 WBNS.

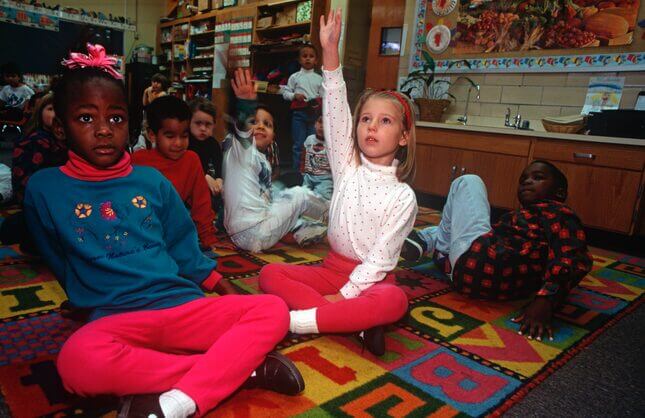

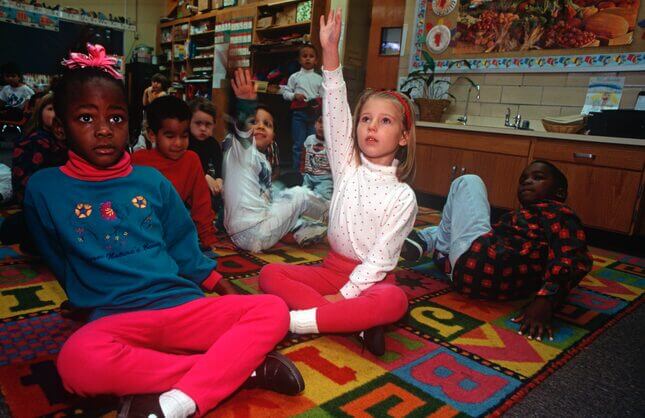

Black youth are abandoned and condemned by authoritative voices at school and sometimes at home. They’ve been trained to bear unfairness while functioning in dysfunctional spaces. Yet, while white youth have been extensively examined and assessed through the years, the ongoing crisis crippling the survivability of Black boys and girls hasn’t been on the radar in the same way. “I think in the past, suicide—or suicidal behavior—was just thought of as a white thing,” Sheftall told the New York Times last fall. But based on the trends that Sheftall and other researchers have lately uncovered, particularly among Black girls, it appears that we should be in emergency mode.

What Black kids—and especially Black girls—are dealing with

The kids are not doing alright. The arrival of covid wreaked havoc on whatever young people once considered “normal,” distancing them from their peers and stretching a shadow of uncertainty and fear over their developmental years. Against this backdrop, the mental health of young people became more closely watched than ever, and numerous reports, like the New York Times’ extensive look at teens suffering from anxiety and depression in lockdown, have laid bare a crisis. Between the start of covid and early 2021, a quarter of kids reported depression. and one in five reported anxiety, according to a study published last August.

That brings us to the state of Black youth in America. Despite the common assumption that white kids are more prone to suicide compared to other groups, Black youth suicide is alarmingly on the rise. A 2018 study found that the rate of suicide among Black kids under the age of 13 was about twice that of white kids under 13. That same year, suicide became the third leading cause of death in Black teens, and the second leading cause of death in Black kids under the age of 14, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

In January, California reported the state’s suicide rate among Black youth had doubled since 2014. We are reminded daily that Black people are disproportionately killed by police brutality in America, which the U.S. Surgeon General cited in a December 2021 advisory on youth mental health. Thanks to the accessibility of social media, Black kids are more aware than ever before of the history of violence against younger victims, like Tamir Rice—undoubtedly a source of brewing inner turmoil.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-