America’s Child Welfare System Doesn’t Keep Kids Safe

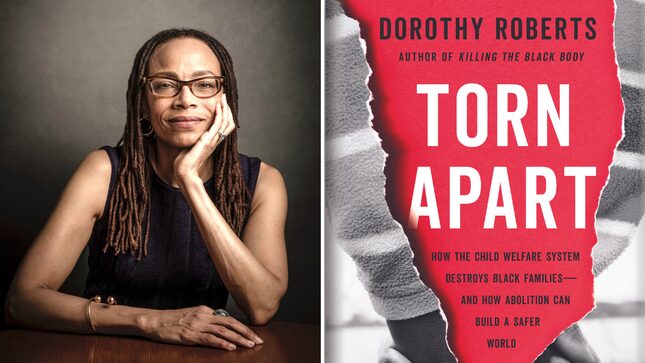

Reproductive justice scholar Dorothy Roberts' new book analyzes the violence it inflicts on Black families—and makes a call for abolition.

In DepthIn Depth

A few weeks before Vanessa Peoples was hogtied by Colorado police and taken to jail, her toddler wandered away from a family picnic. Though Peoples quickly caught up to him, a stranger who found the child called the cops, who in turn wrote the Black mother of two a ticket for child neglect.

On the day of her arrest in 2017, caseworkers paid a visit to her home to follow up on the citation. Peoples, who is partially deaf, was in the basement doing laundry and didn’t hear their knocks. When the officials spotted one of her sons through a window, they called the police, who entered the home, sparking a confrontation. Peoples’ shoulder was dislocated as her hands were bound behind her back and connected to her ankles. Police carried her out of her home, tied up, she later said, “like an animal.” In order to avoid a prison sentence, Peoples pleaded guilty to reckless endangerment. Later, she received a settlement from the police department after filing an excessive force suit.

Dorothy Roberts recounts this story in her new book, Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families—and How Abolition Can Build a Safer World, which was released Tuesday. Peoples’ is one of countless families, mostly poor and disproportionately Black, whose lives have been upended by encounters with child protective services—encounters that can be triggered by incidents as minor as a mischievous toddler making a moments-long escape. Through exhaustive research and analysis, Roberts argues that the child welfare system would be better understood as a “family policing system,” and that children could be safer overall were it to be abolished.

“When you take into account how similar the so-called child welfare system is to criminal law enforcement,” Roberts told Jezebel during a Zoom interview, “it’s very clear that they are operating under the same carceral logic, and they also operate hand-in hand. They’re symbiotic systems.”

The statistics cited in Torn Apart are alarming: More than half of all Black children in the U.S. are subjected to a child welfare investigation before they reach adulthood. The figure for white children is around 28 percent, and overall, more than a third of all American kids are investigated by child protective agencies by their 18th birthdays. A majority of these investigations are closed without any finding of maltreatment, but the process alone subjects parents to massive stress, and has been found to increase rates of depression in mothers without improving outcomes for families. In cases in which authorities decide that reports of mistreatment are substantiated, disparities persist. Black children are overrepresented in foster care, and parental rights in Black and Native American families are terminated at more than twice the rate of white families. Each year, a total of around 250,000 American children enter foster care, with another 250,000 entering the poorly documented “shadow” foster care system, in which caseworkers convince parents to turn their children over to family or friends in order to avoid official involvement with the child welfare system.

Roberts is a celebrated scholar and University of Pennsylvania law professor. Much of her work examines reproductive issues, and her 1997 book Killing the Black Body, which analyzed America’s history of abusing and criminalizing Black mothers and attempting to curtail their rights to bear and raise children, has become an anti-racist classic. Her research, which found her investigating the “crack baby” myth and the higher levels of drug testing of pregnant Black women and their newborns, led her to the child welfare system. Roberts first examined it at length in her 2002 book Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare. Now, she’s become one of the most prominent voices in the movement urging the abolition of the child protective system as we know it.

The number of children in foster care has fallen over the years between the publications of Shattered Bonds and Torn Apart, though Roberts noted that, in some areas, rates are once again rising. Still, the system is too-little changed. “The fundamental philosophy remains the same,” said Roberts, “which is that the way to deal with the needs of children and families is to accuse them of child maltreatment, investigate them, threaten to take their children and supervise them, remove children and put them in foster care, and, in too many cases, permanently destroy the family.” Rates of racial disparity in the system have shrunken, but remain glaring.

“When you take into account how similar the so-called child welfare system is to criminal law enforcement, it’s very clear that they are operating under the same carceral logic.”

Many of these disparities are rooted in the disproportionate rates of poverty that Black families experience. The majority of children in foster care were removed from their homes not due to abuse, but after the state determined that they were suffering from neglect. Many of these cases of neglect land on the radar of child protective services after families find themselves unable to pay their rent or utility bills, buy food or clothes, or persuade their landlords to make necessary home repairs. While less than 8 percent of white Americans live in poverty, more than 18 percent of Black Americans do.

With poverty also often comes increased contact with professionals who are mandated reporters of potential child abuse or neglect. Caseworkers have been found to hold biases against Black families: In Torn Apart, Roberts describes an experiment in which caseworkers were shown the same digitally altered image of a messy home, featuring either a Black or white baby. When presented with the Black child, they were more likely to determine that the baby was being neglected.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-