Fake Bump Conspiracy Theories Prove That Americans Still Can’t Handle Public Pregnancy

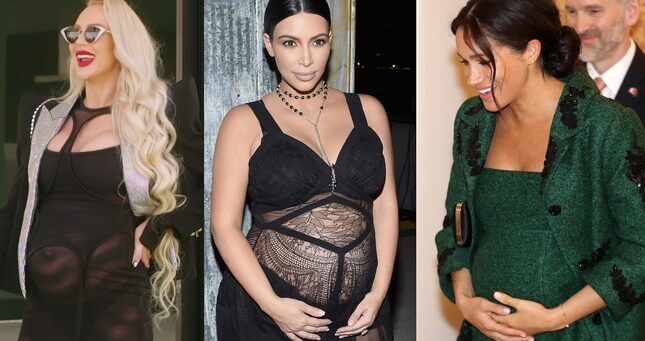

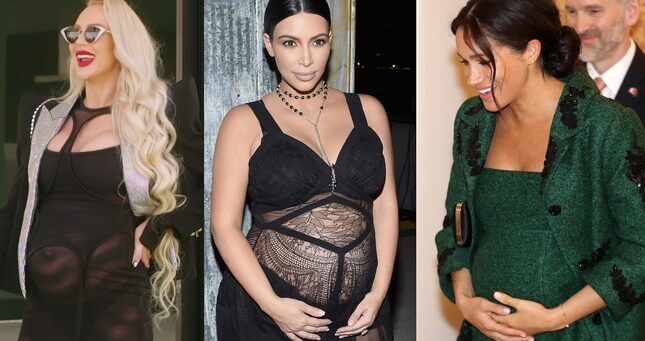

Selling Sunset's Christine Quinn is just the latest celebrity to run afoul of deep-seated cultural anxieties around pregnancy and birth.

In Depth

The latest season of Netflix’s Selling Sunset offered its usual combination of workplace drama and luxury home tours, as the series continues to chronicle the friendships and careers of a coterie of luxury real estate agents in Los Angeles. But it also produced something a little more unexpected: a conspiracy theory.

The show’s scene stealer, Christine Quinn, gave birth to her first child over the course of the season, managing to juggle pregnancy, new motherhood, and her role at the center of at least three feuds. After the series was released in full on the streaming platform, fans lobbed a familiar accusation—that Quinn was never pregnant at all. Social media users remarked that she had remained strikingly thin throughout, appeared spry while wearing towering stilettos days before giving birth, and had performed yogic feats too soon after what she described as a traumatic emergency C-section. Fans would go on to compare dates of Quinn’s appearances at events with the timeline of her pregnancy for evidence, all in an effort to support the idea that she had perhaps become a mother via surrogacy while faking her pregnancy with prosthetics.

Quinn is far from the first celebrity to be accused of doing so. Beyoncé, Kim Kardashian, Meghan Markle, and other women in the public eye have been the targets of similar theories. Last year, the Atlantic profiled one internet conspiracist who devotes her days to amassing evidence that, among other alleged sins, Benedict Cumberbatch’s wife Sophie Hunter staged her pregnancies. But while the fake bump truthers have been scrutinized as one of the most women-inhabited corners of the conspiracy world, less attention has been directed towards why pregnancy is the focus of these conspiracies, and not other aspects of these very public women’s very public lives. Their allure might lie in the fact that public pregnancy is a relatively new American development, one that our culture is still struggling to negotiate.

From “confinement” to “bouncing back”

For much of the nation’s history, respectability demanded that pregnant people become as invisible as possible. Working-class women who couldn’t afford to stay home concealed their stomachs with maternity corsets, and the precursors to today’s maternity clothes weren’t sold in stores until the early 20th century, when a designer named Lena Himmelstein Bryant Maslin began creating dresses with elastic waists for her New York clientele. “Someone had the nerve to say, ‘Do you mind making a dress for me while I’m pregnant?’” medical writer Randi Hutter Epstein told Jezebel. “You weren’t really supposed to go out. Walking out with a pregnant belly, you might as well just be naked.” The idea was so taboo that the company—which would later become famous as Lane Bryant—struggled to find newspapers that would accept its advertisements.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-