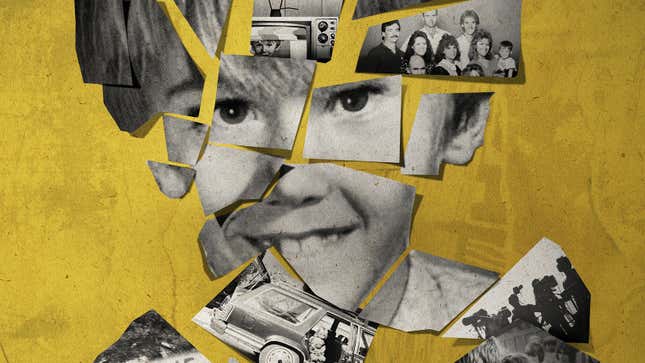

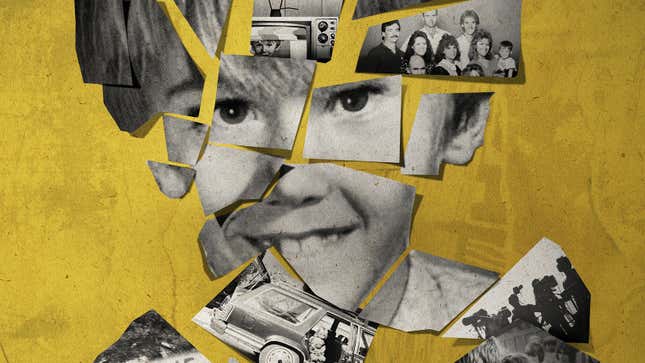

‘Captive Audience: A Real American Horror Story’ and the Fallacy of ‘True’ Crime

The new Hulu doc on Steven and Cary Stayner asks big questions about the faulty nature of storytelling, and why we crave it anyway

EntertainmentTV

At first blush, it may seem that director Jessica Dimmock is spinning her wheels on well-worn terrain with Captive Audience: A Real American Horror Story. Don’t let initial impressions fool you, though—this is an uncommonly deep riff on true crime that transcends so many of the genre’s trappings. The three-part Hulu series is, broadly speaking, yet another retelling of brothers Steven and Cary Stayner’s adjacent tragedies. In 1972, Steven was famously kidnapped at age 7, only to escape his captor, Kenneth Parnell, in 1980 to much fanfare. In archival footage shown in the doc, Today host Deborah Norville tells Steven that if his story were fiction, it probably wouldn’t be believable. Years later in 1989, the night before the Emmy Awards, for which the TV movie based on Stayner’s ordeal, I Know My First Name Is Steven, was nominated in four categories, the former captive was killed in a freak motorcycle accident. Then and there, any notion of a happy ending for a man who rescued himself (as well as another young boy that Parnell had kidnapped) was put to bed. In truth, that notion had already been destroyed by Stayner’s lingering trauma and his resistance to treatment (his father was also outspoken about not believing in therapy). And then, in 1999, Steven’s older brother Cary killed four people in what became known as the Yosemite Killer case. He was eventually sentenced to death, and remains on death row today (there hasn’t been an execution in California since 2006).

At the start of Captive Audience, Dimmock shares her dilemma: She’s telling a story that has been told so many times before. Steven Stayner was an icon in the Stranger Danger-obsessed ‘80s—the two-part TV movie about him attracted a massive audience of 40 million. Cary Stayner has been depicted some dozen in various media—a 20/20 episode from 2019 attempted to summarize the Stayner brothers’ dual tragedies. Kay Stayner, mother of five including Steven and Cary, voices a bit of frustration in Captive Audience over the fact that her sons’ story is the topic of yet another media dissection. She wonders how everyone isn’t already aware of a tale that now stretches back 50 years.

What separates Dimmock’s endeavor—and its excellent product—from those that came before is sheer access—family members (including Steven’s widow Jody and his surviving children, Ashley and Steven Jr.), neighbors and classmates of Steven’s when he was living with Parnell and known as “Dennis,” journalists, Cary Stayner’s mitigation specialist Michael Kroll, and more, weigh in. Interviews conducted by I Know My First Name Is Steven screenwriter J.P. Miller allow us to hear directly from Steven and Cary Stayner, as well as Miller himself as he openly shapes Steven’s horrific experience into something that can be consumed by network TV’s mass audience.

Dimmock allows these accounts to echo and clash—Ted Rowlands, a journalist who interviewed Cary Stayner soon after he was arrested for murder, swears that his goal was to outdo Steven, a media darling of sorts after heroically rescuing himself. Kroll counters, “That’s as far from the truth as you can get. He was fame-averse.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-