Half-True Crime: Why the Stranger-Danger Panic of the '80s Took Hold and Refuses to Let Go

In DepthIn Depth

Illustration: Chelsea Beck/GMG

Adam Walsh, 6, was abducted at a Sears; two weeks later, his head was found in a drainage canal. Yusuf Bell, 9, never completed the errand he was running for his neighbor; two weeks later his body was found at an abandoned school. Johnny Gosch, 12, went missing while delivering newspapers in his neighborhood. He was never found.

All of these stories are real, all of them garnered national attention in the United States, and all of them scared the shit out of people during the early 1980s. It was a time when there appeared to be a growing crisis of child abduction that started gaining traction in the previous decade with other high-profile nonfiction horror stories of missing children (including those of six-year-old Etan Patz, who disappeared in 1979, and Steven Stayner, who was kidnapped in 1972 only to escape in 1980).

The fear of strangers had a vise-like grip on the United States for much of the early ‘80s—it loosened as the decade went on but its handprint remains visible on our culture even today via legislation and, especially, fringe conspiracy theorists whose mission is very much aligned with a tradition made possible by the inflating of statistics and scapegoating of various groups of citizens, all in the service of protecting our children. “The fear that organized conspiracies of deviants exploit children is central to contemporary concerns about threats to children,” is a sentence that could have been written yesterday to describe QAnon; it appears in sociologist Joel Best’s book Threatened Children, which was published in 1990.

“A similar discourse swirls around QAnon today as was seen in the late 1970s/early 1980s,” Dr. Paul Renfro, who teaches history at Florida State University and this year published the book Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American Carceral State, told me via Zoom recently. “There are similar structural factors that one can identify whether it’s a flagging economy or loss of faith in government institutions or anxieties concerning race and racism. These contributed in part to the rise of Ronald Reagan and are present today.”

To be a child in the early ‘80s was to be acutely aware of the possibility that you might be decapitated. The can’t-unsee-able murder of Adam Walsh was made further indelible by a TV movie that aired in 1983 to a reported audience of 38 million people. In my household, we referred to Walsh by his first name, as did the title of his TV movie, Adam. Looking back, it strikes me that Adam was the first mononymic icon I’d encounter. Before there was Madonna or Cher, there was Adam. He was everything I did not want to be: kidnapped and dead.

Being highly attuned to pop culture meant that I was bombarded with stories about child abduction. Elements of the Patz case were woven into the fictional storyline of the 1983 film and eventual cable mainstay Without a Trace (though at least that kid got a happy ending). Bell’s story, as well as that of more than 20 other kids who disappeared in Atlanta from 1979 to 1981, factored into the 1985 TV movie Atlanta Child Murders. Stayner got his own TV movie biopic, a two-night affair that aired in 1989 titled I Know My First Name Is Steven.

Interspersed were entirely fictional accounts: The anti-hitchhiking Afterschool Special called Andrea’s Story: A Hitchhiking Tragedy; anti-stranger messaging tacked onto the end of cartoons like G.I. Joe, Jem, and M.A.S.K.; a Welcome to Pooh Corner episode devoted to the perils of strangers; The Berenstain Bears Learn About Strangers in book and animated episode form; multiple episodes of Diff’rent Strokes that depicted molestation and abduction.

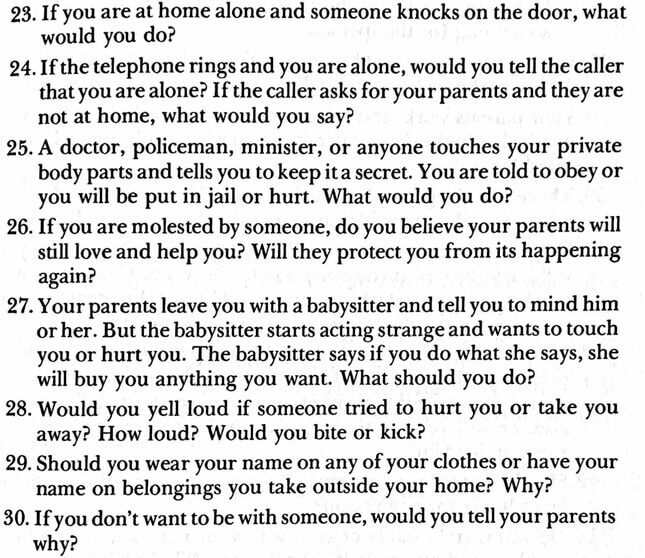

Missing children appeared on milk cartons. There were board games like Strangers and Dangers, PSAs by McGruff the crime dog (whose gravely voice did nothing to assuage my anxiety), school assemblies featuring puppets and robots. Books were published for parents to read with their children—Laura M. Huchton’s 1985 guide Protect Your Child, for example, features a 50-question survey and a first chapter titled “There Is No Such Thing as Overprotection.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-