Abortion Is a Fundamentally American Act

In early America, abortion was common—Ben Franklin published tips on how to do it—and women were trusted to know their own bodies.

In Depth

Illustration: Allison Corr

By the middle of the 19th century, Ann Lohman was rich—the owner of furs and jewels, a woman who made her way through New York City in a carriage pulled by four horses. She built a brownstone on 5th Avenue; the Vanderbilts would later build three homes across the street. For a woman who’d once been a maid and seamstress, it was a remarkable turnabout of fortune. The source of her wealth? Under the name Madame Restell, Lohman worked as an abortion provider. Her job was no secret: She advertised her services in newspapers.

But Lohman practiced during a tumultuous moment in American history, amid the nation’s first major anti-abortion movement. It was a time that, like our own, found avenues to legal abortion narrowing and providers under attack. “There really is this outrage towards her,” said University of Illinois professor Leslie Reagan, the author of When Abortion Was a Crime. Restell was “pursued,” Reagan said, and arrested more than once for providing abortions.

Part of what makes stories like Madame Restell’s so fascinating is that, just a few years before her reign as an infamous tabloid fixture, abortions were legal in New York and every other state. In fact, some form of abortion has been widely legal for much of American history, centuries before the 1973 Roe decision.

Despite a raft of state laws between 1820 and 1880 criminalizing them, by the end of that century, doctors believed that 2 million abortions were being performed annually in the United States—which would have made the procedure far more commonplace than it is today.

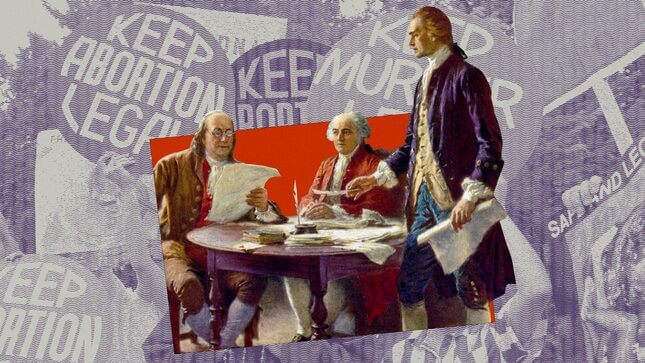

The story of abortion in America is longer than the United States itself. It’s a story that includes centuries-old English laws permitting the practice, which colonizers brought with them to the U.S. It features founding father, Benjamin Franklin, who personally published an abortion recipe, and it’s the story of a time when even the Catholic Church permitted abortions. It’s a story that suggests, you could say, that abortion is a foundational American act.

Abortion isn’t mentioned the Constitution—but that doesn’t mean it’s not a constitutional right.

In his horrifying opinion for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that gutted Roe v. Wade, Justice Samuel Alito wrote, “The Constitution makes no reference to abortion.” That’s true, technically. But it doesn’t mean that we don’t have a constitutional right to abortion.

The 9th Amendment—penned by founding father James Madison himself—explains that rights spelled out in the constitution don’t preclude the existence of other, unenumerated rights. But despite the fact that this support for unenumerated rights is literally spelled out in the Bill of Rights, “Justice Alito does not even reckon with the 9th Amendment in a real way,” said New York University law professor Melissa Murray in an interview conducted after the Alito draft leaked but before the final Dobbs ruling was released. Instead, he argued that Roe was “egregiously wrong from the start,” in part because it was “not deeply rooted in the nation’s history and tradition.” Under the Supreme Court’s previous rulings on the 14th Amendment, Americans are entitled to rights that aren’t explicitly outlined in the constitution if those rights are “deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions” and “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.”

“Justice Alito does not even reckon with the Ninth Amendment in a real way.”

Even in the constitutional test he did choose to apply, Alito’s opinion is full of distortions of history. “He notes that abortion has been criminally proscribed in many jurisdictions in the United States historically,” said Murray, “but he’s a little selective about that history, because it’s not entirely true.”

Alito’s wording in Dobbs is important, in that it is utterly dismissive of much of the nation’s history and tradition—the same history and tradition conservatives are supposedly so keen on preserving.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-