The Intertwining Lives of a Notorious Abortionist and America's First Woman Doctor

In Depth

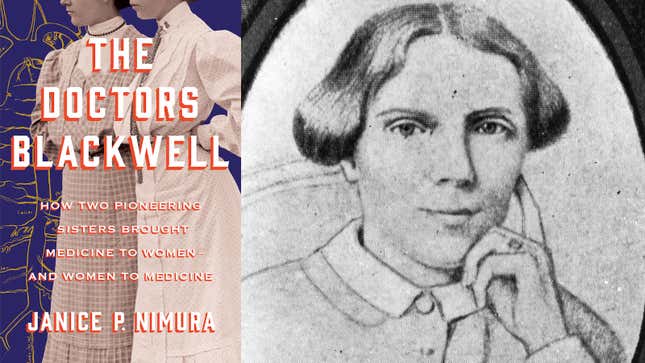

Image: Book cover WW Norton; Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

On September 12, 1851, a small item appeared in the New-York Daily Tribune, the city’s largest and most progressive newspaper. “Miss Elizabeth Blackwell, M.D., has recently returned to this City, from a two years’ residence abroad,” it announced. “Miss Dr. B., we understand, has just opened an office at No. 44 University-place, and is prepared to practice in every department of her profession.”

In 1849, at the age of 28, Elizabeth Blackwell had become the first woman in America to receive a medical degree, from tiny Geneva College in rural upstate New York. Elizabeth had completed her training with some of the most prominent physicians in Paris and London, and at last she was ready to start a practice of her own. But in 1851 the term “female physician” meant something quite different from “woman with a medical degree.” For most New Yorkers, it meant one person: Madame Restell.

Two decades earlier, a woman of twenty named Ann Trow Summers had emigrated to New York from England. She and her entrepreneurial husband, Charles Lohman, surveyed the opportunities for advancement and settled on the thriving trade in patent medicines, with a nom de guerre that became a household name. In March 1839, they ran their first advertisement in the New York Sun, addressed “to married women” and laying out the argument for birth control forty years before Margaret Sanger was born. “Is it moral for parents to increase their families, regardless of consequences to themselves, or the well being of their offspring, when a simple, easy, healthy, and certain remedy is within our control?” asked the ad. Interested parties were directed to an office on Greenwich Street and the services of one Mrs. Restell.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-