Writing My Book About Women Football Players Helped Me Leave My Husband

Queer histories are crucial, even when they don’t seem relevant.

In DepthIn Depth

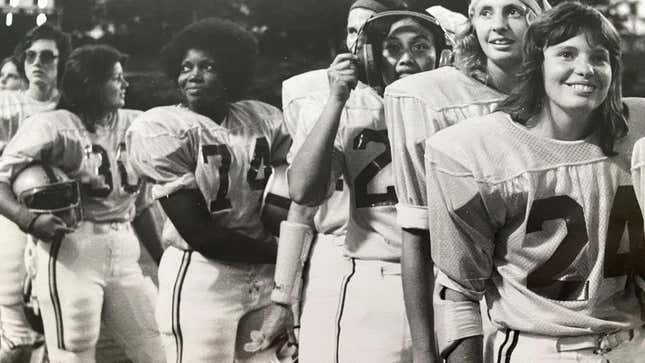

Photo: Photo provided by Rose Low, L.A. Dandelions

I was two minutes into my second interview of the book project when my interview subject–a loud-talking, Southern-drawling woman named DA Starkey–stopped me.

“You know we were all gay, right?” she boomed into my ear.

I laughed in response. “Well,” I replied, “I didn’t want to assume. But now that you’ve mentioned it, let’s talk about it.”

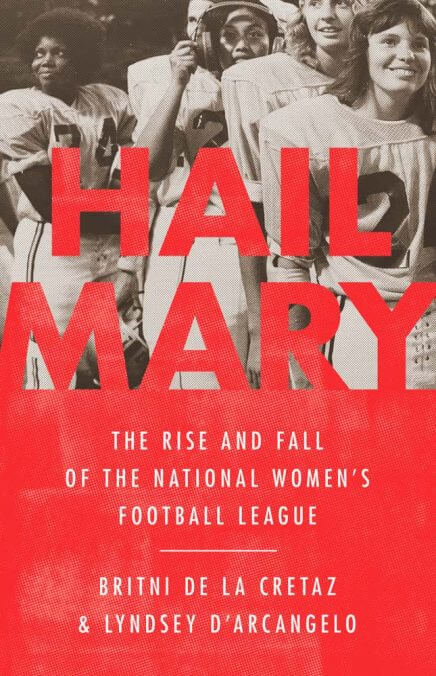

That book, Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League, was about the National Women’s Football League, the first professional women’s football league in U.S. history. The league existed from 1974 to 1988, launching during the women’s liberation movement and shortly after the passage of Title IX in 1972. It also existed in a post-Stonewall era, but many of the cities where the teams played were in less liberal areas of the country throughout Texas, Oklahoma, and Rust Belt states like Ohio. As a result, my co-author Lyndsey D’Arcangelo and I weren’t sure if the book would end up being explicitly queer.

We assumed that a good number of the players would be gay—not because we’re ones to buy into stereotypes, but because we’d seen their photos and read a little about the athletes and, as queer people ourselves, we tend to have a sixth sense about that kind of thing when we see it. What we didn’t know was whether any of the women would talk to us about being gay, whether they saw it as important or connected to their time in the league, or whether it was something they would want to discuss publicly at all. I’d reported on queer women playing in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League two decades prior, and it was impossible to get any of them to speak about it. They usually changed the subject with a brief, “We didn’t talk about any of that.” I wasn’t sure if this would be the same.

So when Starkey very quickly let me know that she was and had always been, in her words, “gay gay gay,” I was relieved. Because, sure, while we can write a book about a women’s football league without ever mentioning whether any of the women were lesbians, or by making it a footnote instead of a central theme, that book can never be the whole story. By telling a story that includes who these women were—who they really were—you can actually get a fuller sense of what this league was and what it meant to the women who played. Because the story of the NWFL is a sports history story, and it is a women’s history story, but it is also a queer history story.

Let’s get one thing out of the way: Not all of the women in the NWFL were queer. But estimates from the players range anywhere from 50-75% of their team being gay. “I knew a lot of the players already because we hung around in the gay bars together,” Starkey told me. “I came out to my parents when I was 14 years old. My dad said, ‘Well, sister, that’s a hard life, good luck,’ and it was never spoken about again. But I didn’t ever change, I was just a dyke. And it wasn’t a big deal back then! You know, people weren’t—we weren’t ridiculed for being gay! I never was.”

As soon as Starkey told me that she was gay and that she’d learned about the Dallas Bluebonnets in her local lesbian bar, there was no doubt in my mind that that bar scene, and the lesbian culture in middle America in the 1970s, would be central to the story we were trying to tell. For Starkey and many of the other players, their queerness was not just a footnote—it was the axis on which their participation in the league revolved.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-