When Your Skin Condition Becomes Viral Content

Latest

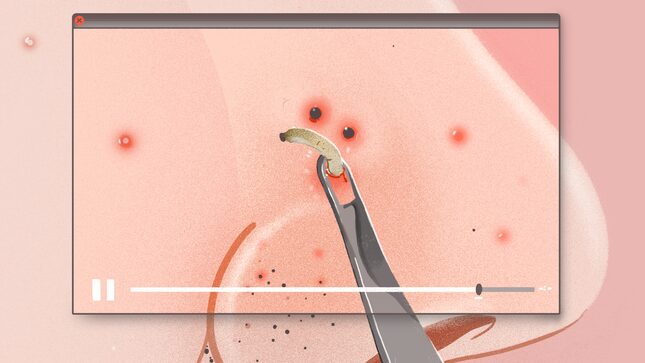

A man waits in a dermatologist’s office, about to be rid of a beastly growth that’s been tormenting him for years. He sits, gowned, until the doctor—gloved, wielding an extractor and making incongruous small talk about take-out and the weather—starts in on his skin. She exerts increasing pressure on the stubborn pustule, pushing and pushing until—POP! Pus spurts forth like a geyser, dense orbs of dead skin are scooped and snipped from their confines, ribbons of pus and blood stream over otherwise even terrain. And then it’s all over: the wound is cleansed, the ooze is stemmed, and the grateful patient is pimple-free.

The pimple pop video is the perfect overshare: it allows us to indulge our armchair voyeurism, get just grossed out enough, and experience a satisfyingly pus-filled narrative climax.

Thanks to the power of the internet, minor dermatological procedures no longer simply unfold in the privacy of the exam room. Dermatologist Dr. Sandra Lee, perhaps better known as Dr. Pimple Popper and the founder of SLMD Skincare, has turned pimple popping into her digital stock and trade, broadcasting hundreds of videos in all their oozy glory on YouTube and Instagram. Lee’s videos are ostensibly educational, but her millions of followers don’t turn out in droves for how-tos on washing your face or applying sunscreen. They come for the pops. Lee has mastered pimple popping’s particular viral alchemy, and the internet shudders with collective disgust and delight when she goes to work on an extra-bulbous pimple—or cyst, or lipoma—and sets it free.

When Lee first launched her Instagram account several years ago, she realized that her extraction videos got far more likes than the rest of her content. “Since then, it was like, I kept throwing logs in the fire, just to see what would happen,” Lee told Bustle earlier this year. It turns out there was an internet subculture just waiting for her: self-proclaimed popaholics who use pimple popping videos as a backdrop to study or fall asleep, and who take to Reddit to share their juiciest pops. Lee figured she was onto something. So she started her YouTube channel, and the Dr. Pimple Popper brand—and internet pimple popping phenomenon—was born.

But does turning patients’ bodies into content count as normalization?

Lee is different than other celebrity doctors—what she offers is noticeably more intimate, and noticeably grosser, too. The pimple pop video is the perfect overshare: it allows us to indulge our armchair voyeurism, get just grossed out enough, and experience a satisfyingly pus-filled narrative climax. Plus it’s easy to like Lee. She is perfectly coiffed and bronzed, noticeably wrinkle-free, and calm and steady in the face of volcanic zits. She makes easy small talk with her patients, checking in throughout the procedure and personifying their pustules with names like “the black hole” and “Momma Squishy.” She routinely breaks the fourth wall, talking to her patients about the fans who will see their videos (and once, even saying hi to her assistant’s mother). It all amounts to engrossing video—there’s something about a gaping pimple brought to resolution that makes it hard to look away.

But for me, something doesn’t feel quite right.

I have severe eczema. As a child, my mother schlepped me to doctors all over the country, trying the treatments they proffered (plus acupuncture, plus Chinese medicine, plus homeopathy) to no avail. Over the years, doctors have deemed my hands, feet, legs, back and breasts all dermatologically interesting enough to photograph. The pictures might end up in a paper or a text book, they said, or maybe displayed at a conference. My mom, a scientist, signed the consent forms. Later, I did too. I have no idea where any of those photographs went.

When I watch Lee’s videos (which on some level, I confess, I find weirdly captivating), I can’t help but feel a little skeezed out. And it’s not the pus or incisions that make me feel gross. It’s that Lee’s brand is built around her patients’ ick factor, and her audience’s desire to see something grotesque. Her collateral—those hundreds of procedures caught on video—relies on patients’ messed-up skin, and Lee’s capacity to restore it to something more palatable.

I got in touch with Dr. Lee via email, who took umbrage at that characterization of her work. “I don’t think any of my patients are grotesque and I never treat them like I think they are gross or disgusting,” Lee wrote. “I never want them to feel embarrassed by the conditions that they have. In fact, I’m normalizing human skin issues, and creating dialogue around it.”

But does turning patients’ bodies into content count as normalization? And is it possible to normalize a person with a skin condition when you focus solely on a procedure intended to remedy whatever they (or their doctor, or our beauty-obsessed society) deem is amiss?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-