What Happens When You Tell the Internet You're Pregnant

Latest

A month after I ordered prenatal vitamins on Amazon, I started hearing an ad on Spotify that featured the sound of a baby’s heartbeat. It was an ad for a prenatal doctor.

“Fuck,” I thought, “the Internet already knows I’m trying to get pregnant.”

But it was impossible to know if it was an example of Target-style omniscience or Spotify accurately targeting my general demographic: Woman listener of child-bearing age. (When I reached out to Spotify, a spokesperson said she was unable to tell me how the ad wound up in my mix.)

When Princeton professor Janet Vertesi got pregnant a few years ago, she went to great lengths to hide her baby bump from the world of big data. She didn’t want her unborn child to be tracked by advertisers and data brokers, so she paid for maternity clothes in cash, used Tor to surf baby sites, ordered baby products to an Amazon locker, and forbade friends and family from discussing the good news on Facebook or via texts.

When I set out to have a child, I decided to do the opposite. I’d download and use the many apps and tech being marketed to women who are pregnant or trying to conceive, and I’d monitor the information flows to see who was actively spreading the word about my efforts. These apps are widely used by the breeding set; I wanted to see what the privacy harms are for those not willing to go to Vertesi’s lengths.

I downloaded a dozen of the most popular apps for wannabe baby mommas. I’ve never had so many pink icons on my phone before: Glow, Nurture, Eve—which are all made by one company started by Paypal co-founder Max Levchin—Clue, What to Expect, P. Tracker, Pink Pad, and WebMD Pregnancy, among others. There are over 165,000 medical apps out there, and based on my cursory search, it seems like a whole lot of them want to know what’s happening in your uterus.

They asked me about my mood, when and how I was having sex, whether it was painful, my weight, whether I exercised, whether I got wasted or smoked, and of course, whether I was having a period and how heavy it was.

Midway through the experiment, Consumer Reports revealed that period-tracking app Glow had a security flaw that would have let any snoop who knew my email address look at all that information. That wasn’t exactly reassuring, but I persisted. And I kept using Glow, as it was one of my favorites and they immediately fixed the problems pointed out to them by the journalists.

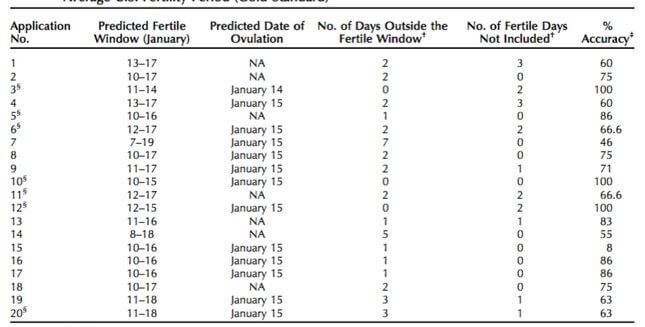

While I was trying to get pregnant, I tracked my periods using apps that told me when I should be having sex to maximize the chance of baby-making. High-school sex-ed classes would have you believe that pregnancy happens as soon as the p gets near the v, but in fact, there are only a few days per month when one has a decent chance of getting pregnant. These apps claim to help you identify them, giving you your chance of getting knocked up each day like a weather app predicting the chance of rain.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-