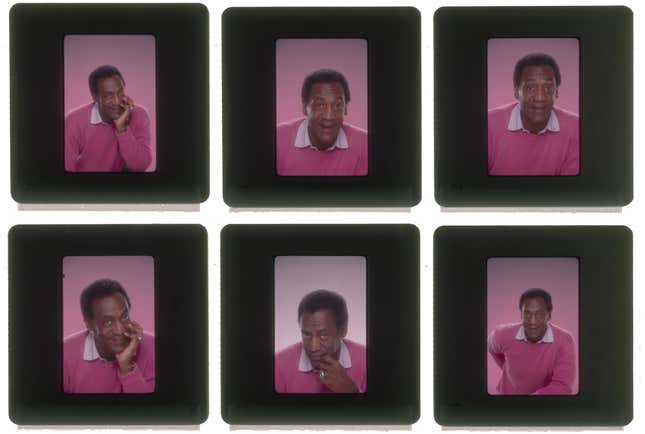

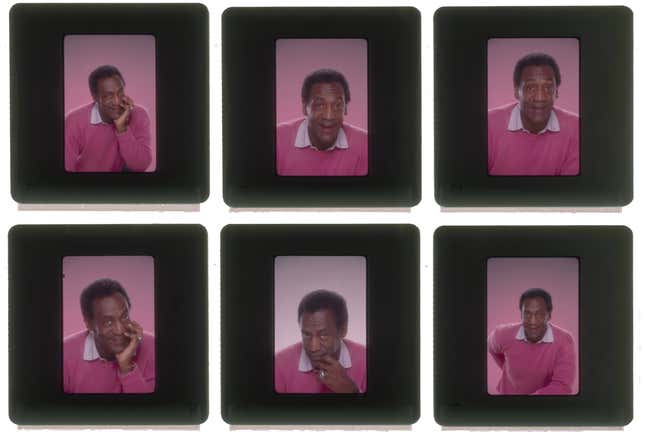

We Need to Talk About Cosby Grapples With The Two Bill Cosbys

W. Kamau Bell's new Showtime documentary explores the accused serial rapist's alleged crimes and legacy.

EntertainmentTV

Last year, Stargirl actor Anjelika Washington—who is Black—revealed that one of her prior roles had paired her with a white stuntwoman who performed in blackface and an afro wig. Washington complained to a producer, who suggested that she should just feel grateful to have the job. “There’s this oppressive thing that often happens when everyone and everything are ran by white people on sets (and in any industry) where they try to manipulate POC into just being GRATEFUL to be there,” Washington wrote in an Instagram caption. “They do this to us because they know that they literally run the show.”

I didn’t imagine Showtime’s new documentary series, We Need to Talk About Cosby, would teach me about the too-little-known history of Black stunt performers, but Washington is far from the first black actor to encounter this form of Hollywood racism. When Bill Cosby starred in the action series I Spy in the ‘60s, he refused to participate in the practice of using white stunt people in blackface, which is known as “painting down.” By insisting that Black actors be hired to perform his stunts, Cosby helped open the profession to African-Americans.

He is also accused of drugging, sexually assaulting, and/or raping more than 60 women.

We Need to Talk About Cosby could have been a very different documentary. It might have been called something like We Need to Talk About What Cosby Did, and framed its focus tightly on the crimes he’s accused of and their impact on his alleged victims’ lives. While the four-part series does feature lengthy and harrowing accounts from women who’ve come forward again and again to share their stories of being drugged and assaulted by Cosby, it is also very much about the man himself—his career triumphs, his image-making efforts, his relationship with the Black community. It’s a potentially dicey approach, as an extended exploration of Cosby’s professional life risks suggesting that his value as an entertainer is more important than the lives of the women he’s allegedly harmed. In this case, the risk pays off: The film convincingly argues that a full picture of his alleged crimes and the systems that enabled them would be incomplete without an examination of Cosby as a human being.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-