This New Essay Collection Reminds Us Abusers Can Be Real Charmers

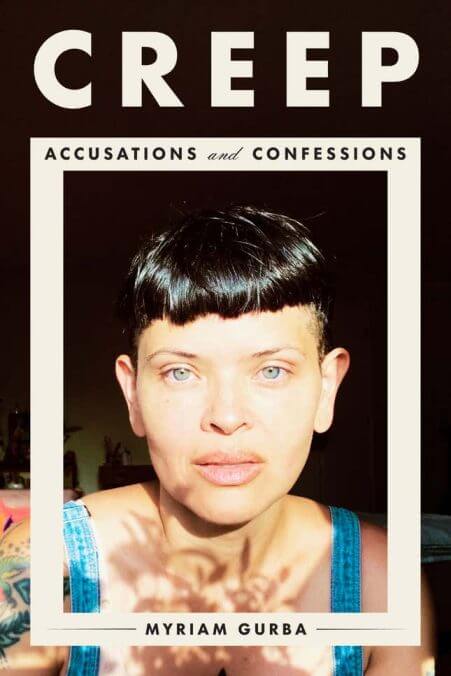

Myriam Gurba, the author of the critically acclaimed new essay collection Creep, talked to Jezebel about her creep—and the creeps lurking all around us.

BooksEntertainment

A creep can be a high school teacher, beloved by his students and colleagues. A creep can be an arduous romantic, relentless in wooing a new love interest. A creep can be your lover-turned-roommate, at different points icing you out and terrorizing you in your own home. A creep can also be more “typical” things: your jailer, your rapist, tormentor, stalker, abuser—the man you eventually feel certain will kill you. Myriam Gurba’s creep—an ex-partner from not so long ago—was all those things to her.

In Gurba’s critically acclaimed new personal essay collection Creep, she introduces us—essay by essay—to all the many creeps and creepy things™ that color her childhood and adulthood, that loom large and monstrous in history and the present. Creep comes after Mean, Gurba’s 2017 memoir detailing her experience surviving rape as a young woman and short skirt-clad “imperfect victim,” as she processes how the man who raped her, Tommy Jesse Martinez, went on to kill several women in Northern California. Martinez was just one predator who invaded Gurba’s world; Creep’s wide-ranging subject matter culminates in a haunting final essay that introduces us to Q, the handsome, literary charmer who swept Gurba off her feet, then spent the next several years physically and emotionally tormenting her to within an inch of her life—all while he was Gurba’s colleague, a fellow teacher at the local high school.

“Broadly speaking, most people are in denial about the extent, the scope, and the scale of gender-based violence,” Gurba told Jezebel. In the U.S., she said, “I think that denial has multiple underpinnings,” one of which is “the idea an abuser is particularly exceptional or special. … People don’t want to acknowledge they can be attracted to perpetrators, that perpetrators can be in certain professions, in helping professions, like, say, teaching.”

With darkness and biting, unexpected humor, Creep wrangles with the disturbing archetypes of perfect victim and perfect predator as two grotesque, conjoined puzzle pieces; some of the white women who posture as saviors while profiting off the suffering of the marginalized; and the pervasive obsession with true crime that often strips female victims of their humanity. After all, some killers will skin their victims and leave them physically faceless—only for particularly shameless storytellers to leave these victims metaphorically faceless, too. Gurba talked about all of this with Jezebel. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

JEZEBEL: The first essays of your new book dive into several chilling true crime case studies. We’ve seen true crime podcasts and storytelling practically become an industrial complex, which can be dehumanizing for victims. How did your personal experience with Tommy Jesse Martinez shape how you approached telling these stories of other victims as real people?

My interest in femicide developed through my own survivorship. As I’ve written in my memoir Mean and as I write in Creep, in 1996 I was sexually assaulted by Tommy while I was walking. He was a serial attacker, a serial perpetrator. A few months after he sexually assaulted me, he sexually assaulted another woman and largely targeted female pedestrians in my hometown, whom he kidnapped, tortured, and killed. Sophie Torres, one of his other victims, was homeless. She was wandering the streets when Martinez crept up behind her and killed her, and so I have experienced a sense of being haunted by her memory, from the guilt that I feel about having lived. And because of that preoccupation with her loss, I’ve developed sort of a relationship with her spirit, where I feel sort of accompanied by her in my daily life. And it’s informed my relationship to all victims of femicide.

I can’t speak on behalf of any woman whose life is stolen as a result of gender-based violence, but one of the things that I can do is defend them from having their stories hijacked by masculinist storytellers, who will, again, turn that story into the perpetrator’s story. I’ll give an example of what I mean by that. I was raised on the myth of [writer and artist] William Burroughs, that Burroughs is this great American writer, that he’s the greatest of the Beats. But he has this legend, this dark and fatal legend attached to him, where his greatness is rooted in the taking of his wife, Joan Vollmer’s, life. By taking her life, she sort of endowed his career with this sort of cannibalism, where she’s tucked away and his writing career is infused with that loss of life. What I’m attempting to do is shift the way that we talk about that legend, and tell the story of Vollmer as a great artist in her own right. What I want to demonstrate to the readers is that the vulnerable final months of her life very much followed a sort of domestic violence pattern. There were so many red flags present that indicated she was on a track toward femicide.

In the final essay of the book, when you’re sharing your story with Q, your abusive ex, there’s a pervading fear of femicide. How did you approach writing about this terror?

The threat of death is always hanging over us—three women a day die of femicide in the United States. We don’t get killed for staying, we get killed for leaving. And that is very much what I want for readers to understand, is that the stakes are so incredibly high. Nobody asks prisoners why they didn’t just leave prison. It’s just as silly to ask those of us who are experiencing intimate partner violence, or who have survived it, why we didn’t just leave—because we’re being held in prison. The threat hangs over us, if we leave we will be executed.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-