The Tattoo Industry Is Having Its Own Wrenching, Revelatory #MeToo Moment

- Copy Link

- X

Katie was 19 when she went to get her first tattoo, from an artist whose work she’d seen on other people’s bodies and admired. In her memory, nothing “super weird” happened that day, though she remembers the artist being flirtatious. The next two times, when she returned to have a new, larger piece done, she says things were different.

“He would very aggressively come on to me, stare at my body in really pointed ways, and grab my ass and touch me while I was getting work done,” Katie, now 24, says. (To protect her privacy, she asked that Jezebel withhold her last name.) “One time he tried to put his hand down my pants and grab my vagina, all while I was on his bench. He tried to corner me in the bathroom, said that he wanted to have sex with me and have me suck his dick, and that I’d get a discount if I did it.”

The artist was Alex Boyko, a 25-year-old tattooer based in the Detroit area. Boyko is a popular artist who specializes in American traditional-style tattoos, and he’s worked or served as a guest artist in shops across the Midwest and in Los Angeles. Katie is one of dozens of women accusing him on social media of sexual misconduct ranging from harassment to assault, and one of many women across the country who are accusing men who tattooed them of sexual misconduct in the industry’s own version of a #MeToo moment. A Tumblr page of anonymous, crowd-sourced accounts about Boyko’s behavior has over 100 text screenshots, all testimonials from women who allege he behaved in sexually violating ways with them. An activist who was alarmed by his alleged behavior and moved to collect more women’s stories estimates there are “at least 200″ women who’ve come forward to make various claims.

“One time he tried to put his hand down my pants and grab my vagina, all while I was on his bench.”

Like Katie, some of the women allege that they were groped during their tattoo appointments, or talked into sending him fully nude or topless photos, supposedly as “reference materials” for future tattoos. And he’s been accused by one woman of giving her a tattoo that was very different than the one they’d agreed upon together, on a highly visible part of her body. Others accuse Boyko of assault outside of work, or of turning consensual sexual situations into non-consensual ones by attempting to perform sex acts they didn’t agree to. And one woman told Jezebel that Boyko “forced himself inside” her one night against her will.

The allegations against Boyko became public after two male tattoo artists teamed up with three Detroit-area women who say they’d been hearing disturbing stories about Boyko for years. The Detroit women eventually shared dozens of messages from women alleging that Boyko harassed or assaulted them in a viral Facebook post and on the Tumblr page.

Jezebel spoke to seven of Boyko’s accusers, including one woman who’d been unaware of the social media campaign against him until we contacted her. Boyko did not reply to several emailed requests for comment. His attorney, Jeffrey Perlman, told Jezebel that Boyko denies every allegation, and said the accusations are a “marketing scam” created by a rival tattooer.

“There’s zero facts to support these claims,” Perlman told Jezebel in a phone call. “This is all a marketing scam by someone who’s disturbingly obsessed with this whole thing.”

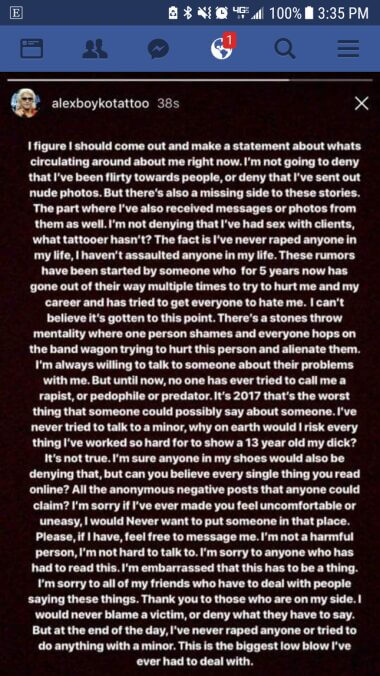

Boyko has, however, issued two semi-public statements on the allegations. The first was on Instagram Stories, meaning that it disappeared after 24 hours. Several people sent a screenshot of it to Jezebel. In it, Boyko says he’s slept with clients (“What tattooer hasn’t?” he wrote) but denies ever sexually abusing anyone or sending nude photos to minors, as several of the Tumblr posts alleged.

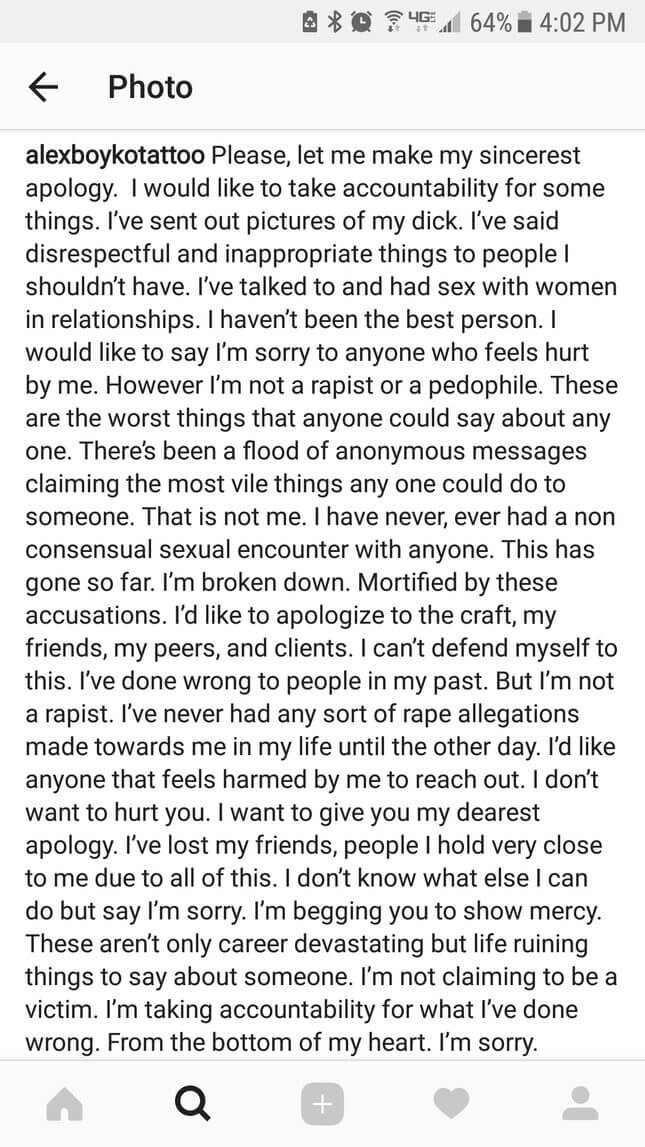

The second post was published as an Instagram photo, which has now been deleted. In it, Boyko calls the allegations devastating and “life-ruining,” but says, again, that he’s never committed rape. He does cop to sending dick pics and making inappropriate comments “to people I shouldn’t have.”

“I’m taking accountability for what I’ve done wrong,” it concludes. “From the bottom of my heart, I’m sorry.”

None of the women involved have filed criminal charges, and Boyko is suing three of the tattoo artists who spoke out against him online for defamation, as well as two tattoo shops. His attorney has also sent cease and desist letters to one artist, whose name is Jon Larson, and to one of the women who organized the social media campaign against him.

“As a tattoo artist, you hear things in the tiny community.”

Larson works at Depot Town Tattoo in Ypsilanti, Michigan. He says he’s known Boyko for five years, and disliked him for almost as long. “I definitely spoke my mind about his character to anyone that would listen,” he told Jezebel recently. He started tweeting about Boyko six months ago, he says, after hearing some odd stories from former Boyko clients, about men being overcharged and women being harassed on social media.

“As a tattoo artist, you hear things in the tiny community,” he says. He found the allegations concerning, but says none of them were as bad as what came later.

The world of tattoo artists may sound rareified, but it’s grown fast and far. If a woman in the Detroit area wants a tattoo, she has dozens of shops and private studios to choose from, featuring hundreds of artists. But some artists are especially sought-after, and before the allegations spread, Boyko was among them, making numerous “best of Detroit” lists and being interviewed in a handful of national publications.

And despite its ever-growing size, the tattoo world, both locally and nationally, functions like a very small town, and word tends to travel quickly. While Boyko is trying to tamp down any discussion of the allegations against him on the internet, the accusations have set off a sizable outcry, and form part of the tattoo world’s broader #MeToo moment: a series of disturbing sexual abuse disclosures, and an intense and ongoing public discussion about what’s normal and acceptable between an artist and client.

Unlike accusations in entertainment or news media, the tattoo world’s reckoning is playing out primarily on social media, in anguished Facebook posts and secret-spilling Instagram Stories.

“People had been trying to bring attention to Alex Boyko for the last couple years,” said one of the women working on the social media campaign against Boyko, Lauren—who asked to be referred to by her first name because she was concerned about being doxxed on social media. She lives in Detroit and has been involved in local activism for several years, while also working a 9 to 5 job. “The posts never gained traction. Nobody really listened. He kept working at shops. I don’t know if they knew what was going on or turned a blind eye, but they kept letting him work there. I think this is a turning point for him and maybe the tattoo community here. And I hope it’ll set a precedent way further spread out than just Michigan.”

In mid-December, Jon Larson, the artist who says he received a cease and desist letter from Boyko, says that after years of hearing secondhand stories about Boyko being a creep, he heard a specific allegation from a friend’s girlfriend: that Boyko had harassed her and made inappropriate comments while she was being tattooed by another artist, during a smoke break when she and Boyko were outside alone together. “I was just fed up and no one was doing anything about it and I was at my wit’s end,” he says. He put a series of posts on Instagram stories, starting with a screenshot of a text conversation with a friend, where they talked about Boyko’s alleged habit of harassing female clients.

“You’ve heard the stories,” Larson wrote over the screenshot. “There are plenty, they are consistent and true.” He urged his followers to pick their artist carefully: “You can drive no less than an hour from Detroit and get tattooed by some LEGENDS of tattooing. Tattooers who will treat you with dignity and respect. Tattooers who respect the craft that has provided them with everything they have and won’t disgrace it trying to take advantage of their clients.”

“The posts never gained traction. Nobody really listened. He kept working at shops.

Over the next day, Larson says he and other artists put up posts on Instagram criticizing Boyko’s alleged behavior. He kept adding screenshots from women who he says were messaging him their own Boyko stories. (While Larson posted screenshots of each of these accusations, they can’t be independently verified by Jezebel.)

“Every time he tattooed me he did some creepy shit,” one woman wrote, adding, “Or has touched me while tattooing me, has put my feet in his crotch. All this while in the middle of tattooing me so I didn’t have anywhere to go, not knowing what to do.”

A second woman wrote that she’d gone to Boyko to get a chest piece done, and he asked her to take off her shirt and bra to trace an outline. “As I took my bra off and was standing there he grabbed my chest and squeezed with his hand,” she wrote to Larson.“I punched him in the shoulder and loudly said, ‘Hey don’t touch me,’ and he told me to be quiet so nobody would hear me.”

“I tried to leave the room and he pulled me back in,” a third woman wrote, about an incident she said happened in a storage room at one of the shops where he worked. “Bent me over the counter, pulled my pants down and tried to force himself inside me. I said ‘no’ and ‘stop’ the entire time and kept trying to pull my pants up but he would just keep pulling them down and forcing himself into me. He finally stopped but only after I told him he was hurting me.”

“I was 13 years old when Boyko emailed me a dick pic,” wrote a fourth woman. “Thank you for sharing all of this!!!”

A common thread in many stories was years of alleged social media harassment across multiple sites: at least two dozen women said Boyko had sent them unsolicited dick pics for years, as well as Snapchat videos of himself masturbating. Some alleged they were under 18 at the time. Six women also said he’d offered discounted tattoos in exchange for sexual favors.

Lauren, the local Detroit activist, was sent screenshots from Larson’s Instagram. She discussed the allegations with two friends. The three of them decided to make a Facebook post to spread the information further. “I uploaded 10 images to start,” Lauren says, alongside a post that referred to Boyko as “a predator.” And then messages started flooding into her inbox, she says, many of which contained more allegations against Boyko. “I was getting messages from dozens of women, every hour.” Some thanked her for sharing the post. Some people didn’t want their experiences shared, she says: “They just wanted someone to talk to.” (While Lauren’s friends worked on the social media campaign with her, neither were comfortable being quoted in this piece due to privacy concerns. One of the two has received a cease and desist letter from Boyko’s lawyer, threatening to sue her for defamation.)*

At some point, Lauren says, she came to the startling realization that she’d had her own experience with Boyko: an unsolicited dick pic on Tinder.

“When I saw a dick pic [one woman had received], I remembered I’d received the same dick,” she says dryly. She knew because, she says, “He has a spiderweb tattoo down there.” (In the course of reporting this piece, I was forwarded a pornographic, self-made video that Boyko sent to one woman. Jezebel can confirm that is the case.)

“I was getting messages from dozens of women from my inbox, every hour.”

Lauren added 42 photos to her Facebook post, the highest number Facebook will allow, and then started adding more in the comments. The post picked up speed, eventually racking up something like 700 comments and 1500 shares.

Elise, who asked that Jezebel refer to her by her middle name in this piece, citing privacy concerns, reached out to Lauren after seeing the post to recount an experience that happened to her four years ago, when she was 21. She told Jezebel that she flirtatiously texted with Boyko for a few weeks, although she knew he had a girlfriend. Boyko, she says, kept telling her he was going to break up with the girlfriend. When she realized that wasn’t going to happen, she says, “I said, ‘We can still be friends, but there’s not going to be any romantic involvement.’”

Soon after, Elise scheduled a tattoo appointment with Boyko, to get two matching designs on her stomach, one on either side. At the time, she says, he was working in a private studio. (Unlike tattoo shops, private studios are spaces where artists do custom work, by appointment only, and don’t take walk-in customers.) Boyko behaved professionally when he traced the stencils for her stomach area, she says, “But other people were around.”

When she went back to get the tattoo, they were alone, she says. “He tried telling me that I needed to take my bra off. He definitely tried to convince me to take as much clothes off as possible.”

Elise kept her bra and pants on, and winced as Boyko started the tattoo and she realized how painful it was going to be. She soon asked for a break, at which point she says Boyko tried to kiss her. She says she had no interest in kissing him back, but did so briefly, then pushed him away, saying, “Later” and “Let’s finish my tattoo.”

“You’re trying to be polite,” she explains. “I really didn’t want to piss him off to the point where he was going to fuck up my tattoo. That was my thought process: I can’t have him fuck up something that’s going to be on my body forever.”

Elise says that as the tattoo process continued, Boyko would periodically stop, grab her hand, and try to place it on his penis. “At one point he took out his dick and tried pushing my head down,” she says.

At that point, Elise decided she needed to get out. Thinking fast, she says she told him, “Let’s have you finish up this half of the outline, then I’ll come back and have you finish up the rest.”

“I can’t have him fuck up something that’s going to be on my body forever.”

Elise left with an incomplete tattoo and never went back. “It’s not colored in or shaded or anything,” she says. “It took him probably 45 minutes to do just that much, because I was so uncomfortable.”

The same week as the disastrous appointment, Elise says she reached out to him, to tell him the visit made her feel “awful and uncomfortable.”

Boyko, she says, apologized, telling her “I thought you were into it.”

“I was like, ‘Why do you think I left early?’” she says. “I wasted my time and money to be uncomfortable.”

A few weeks later, she says she mentioned to another tattoo artist she knew in Detroit that she’d gotten some work done by Boyko. “The minute I mentioned I got tattooed by Alex Boyko, he goes, ‘Oh, did he send you a dick pic?’” Elise says.

Another woman who reached out to Lauren after her Facebook post is a 40-year-old woman who asked to remain anonymous. The woman says she’d rejected his advances several times during a night out in the spring of 2016 with another friend, and, as they were going to sleep for the night in the same bed, she made it explicitly clear she did not want to have sex with him.

“He kept trying to fool around,” the woman says. “I didn’t want to. I just wanted to go sleep.” As they lay in bed, she says, “He pinned me down. It was unreal how quickly this happened. I’m not a small girl. I don’t put up with shit. But he was like a cat. Fast as a cheetah.”

The woman says that Boyko pinned her arms, put his legs on either side of her chest and forced his penis in her mouth. She pushed him off, she says, and he grabbed her, pulled her underwear down, and forced his penis into her vagina. She pushed him off again, telling him, “this isn’t happening,” and finally he stopped, she says.

“He got shitty and pouty and finally we just went to sleep,” she adds.

The woman didn’t consider filing a police report, she says. “The thought never even crossed my mind, honestly. I think after working in bars for 10 years and living through, at that point, 38 years of bullshit, catcalling, and harassment, it was just another day, another shitty dude.”

But she did tell two people at Sun House, the private Detroit tattoo studio where Boyko was working at the time, about the experience. She says they “brushed me off” and Boyko continued working there. (A manager at Sun House didn’t respond to two requests for comment; neither did managers at several other tattoo studios where Boyko has worked in the last three years. Someone who worked at Sun House left a comment on a private Facebook page, which was forwarded to Jezebel by the woman who says Boyko assaulted her. It says that Sun House is a studio where there’s no “owner” as such and everyone works for themselves. But, referring to Boyko, it says, a bit confusingly, “When clients came forward we took action and fired him.” In Boyko’s lawsuit, he says that he resigned from an unspecified job because of the allegations.)

In an effort to determine just how widespread the allegations against Boyko were, I reached out to several women on social media who’d posted about having work done by him, but hadn’t said anything in their posts about his behavior. I asked in a general way how their tattoo experiences had been and was met with yet more stories. One told me that she was aware he was “a womanizer” and, as she put it, “sent pictures of his dick to most of the Detroit metro area,” but hadn’t had a personally negative experience with him.

A second woman, who requested anonymity, told me that he “touched my ass” several times while doing her first tattoo. Figuring it had been a mistake, she said, she contacted him a year later for a second tattoo. She wanted it on her torso, and she said Boyko instructed her to send a topless photo so he could send back a design that would fit her body correctly.

“I was naive, so I sent it,” she told Jezebel. In return, she says, Boyko sent her an unsolicited dick pic, followed by a video of himself masturbating. She still has the video, which she shared with Jezebel. (The woman sent the video voluntarily and we did not ask for or solicit it.) She says he never sent the tattoo drawing, and didn’t respond when she texted him to follow up. (We’ve also seen those texts; the last one she sent, asking if he’d ever drawn her design, is marked as undelivered, suggesting that Boyko may have changed or deactivated that phone number.)

“He’s a predator,” she wrote to Jezebel. But, she added, with a kind of exhaustion that will be familiar to many women, “It’s nothing compared to some other shit men have done. He’s an amazing artist, but he’s a sleazeball.”

Margot Mifflin is a tattoo historian and the author of a feminist history of tattoo art called Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. She says there are structural, historic, and cultural reasons why tattoo shops can be particular sites of harassment for women.

“The tattoo process involves a situation where harassment can happen in the sense that most tattooers are men and most clients now are now women,” she wrote to Jezebel recently. “So you start with an art form that involves touching and often requires at least partially undressing. And you have an active male artist working on a passive/prone female client. The session takes time, so the client has to submit to the artist in order for it to be completed, and if something uncomfortable happens during that time—the guy hits on her, touches her inappropriately, pressures her in some way—getting up and leaving means walking out with a half-finished tattoo.”

That’s one reason, she says, “why some women prefer female artists. They feel safer in the hands of women.”

Mifflin points out that women tattoo artists can be just as vulnerable to harassment, with the wrong bosses or co-workers around. “Women artists working in men’s shops are vulnerable in the sense that there’s no corporate or union oversight to protect workers,” she says. “If someone harasses or assaults you, you there’s no HR to go to.”

“The tattoo process involves a situation where harassment can happen in the sense that most tattooers are men and most clients now are now women.”

Mifflin thinks that at least part of the systemic issue is furthered by tattoo magazines, which she describes as “basically 20th century lad mags,” and which she says promote “biased treatment of tattooed women and women tattooists by routinely showing topless or bottomless women displaying a tattoo on a forearm or an ankle.”

It’s a tough position to disagree with if you’ve ever taken a passing interest in the tattoo industry or paged through a tattoo magazine. Women artists are often showcased in sexualized, pin-up style shoots, many times, Mifflin points out, with their legs spread. (To pick one example out of a vast constellation, she points to Tattoo Society magazine, which recently showcased an artist named Megan Massacre with a cover shoot of her in underwear.)

“There’s nothing wrong with being sexy,” Mifflin says, but there’s an inherent double standard, given that male tattooers aren’t written about next to photo spreads of them panting in their boxers. “It reinforces the old cliché that tattooed women are sexually available, and that their tattoos are there for men’s pleasure.”

Most tattoo artists learn their trade by working as apprentices; professional “tattoo schools” are few, somewhat dubious, and widely looked down upon. Mifflin said that, in the wrong shop, “professional, year-long tattoo apprenticeships can be abusive rites of passage that don’t always involve actual tattooing. And for women, the abuse can be sexual.”

The rules, etiquette, and customs of the craft, then, are handed down in what’s akin to an oral tradition, creating an industry that’s full of guidelines that are practiced but opaque. That can lead confusion for some clients who are new to that world. Boyko’s accusers say he traded on that too, for example by asking for nude or topless photos when they weren’t necessary. And one woman accuses him of a much odder power play: giving her a tattoo she didn’t really want, and steamrolling over her objections.

MW, who asked to be referred to by her initials to protect her privacy, says she was 18 when she went to get a tattoo from Boyko five years ago. She was still living with her parents, she says, and they had requested she only get something that could be easily covered with clothing.

“We had agreed to get something done on my shoulders,” MW told us. He’d sent her a drawing of a snake, which she loved. She paid a deposit and showed up at the shop where he was working at the time, only to find, she says, that he’d changed his mind. “He said, ‘I don’t want to do that one anymore, let’s do something else.”

Changing a design slightly to make it fit the body better or work better as a piece of art isn’t unusual for tattooers, but Boyko, MW says, gave her an entirely different design on her forearm, a highly visible spot.

“To this day, it’s in an awkward place and I wish I’d never gotten it,” she says. She also noticed that Boyko was “grabbing my leg” for the duration of the appointment, she says, “and sitting between my legs the whole time, which I thought was weird.”

When the appointment ended, MW says, “he tried to get me to come over afterwards.” She left, facing the wrath of her parents, who were furious she’d gotten such a visible tattoo.

MW says she’s aware she could’ve refused the tattoo and left, but in practice, for an 18-year-old fresh to the world of tattooing and facing the prospect of losing her deposit money, the decision wasn’t quite so straightforward.

“I really wanted something done by him because I loved his style,” she says. “I drove probably an hour to get this tattoo, I’d already paid the deposit and I was going to lose the deposit if I didn’t do the tattoo that day. He told me if I got this one done he’d give me the deposit back.”

MW had added Boyko on several social media platforms prior to her appointment. “For two more years he harassed me constantly,” she says. “He’d send me inappropriate pictures and videos to the point where I had to block him on multiple accounts. When he saw that I got a tattoo by someone other than him on my arm he berated me for hours, saying I was stupid and ‘That arm was supposed to be mine.’” And after all that, she says, she saw he’d done her same tattoo on someone else, the design Boyko claimed he’d made especially for her. (Repeating custom work on multiple clients is a faux pas.)

Lauren’s Facebook post about some of the allegations against Boyko remained up for six days. In that time, she got messages from about 50 women. Her friends who she’d worked with on making the post say they got more. Larson says he got more. So, according to him, did a friend of his, another tattooer. They estimate that between the five of them, they heard from over 200 people.

“That arm was supposed to be mine.”

Two days after Christmas, Lauren says, the Facebook post was taken down and she was blocked from posting for almost two weeks. Two backup accounts were also banned, she says. In response, the three women created the Tumblr page; when that was taken down, they made another.

Larson faced more serious immediate consequences. He says that he and his business partner tried to file a report with the police in Livonia, Michigan, where Boyko lives and where they say they’ve heard he tattoos out of his house. (That would be illegal; tattoos in Michigan and many other states have to be done in a licensed shop.)

On December 23, Larson says he got a call back from a Livonia police detective. In that message, he says, the detective told him that he could be subject to criminal harassment charges if he continued posting on social media about Boyko.

The detective didn’t respond to a request for comment. A police report obtained through a FOIA request shows that Boyko filed a complaint against Larson on December 22 for harassment. In his statement to the detective, Boyko said he and Larson had bad blood for years, ever since Larson accused him of “stealing” tattoo clients. The statement also says that Larson accused him on social media of being “creepy” to clients, and that he tried to get Boyko’s ex-girlfriend to make a public statement that Boyko was a “bad person” who’d cheated on him her during their relationship. (Larson denies that, telling Jezebel, “I never requested she post anything or for her to take any action against him.”)

“Boyko stated the harassment is impacting his relationships with his clients and his personal life,” the report says. “Boyko reported that all of the claims posted were false.”

On December 26, Larson received a cease and desist letter from Jeffrey Perlman, Boyko’s lawyer. The letter calls the allegations “false and defamatory,” and says they’ve caused Boyko irreparable harm to his career and reputation. On January 12, Boyko filed a formal defamation suit for $25,000 in Wayne County civil court against Larson, two other artists, and two tattoo shops. The suit accuses all the artists of spreading false allegations, and says Larson specifically is trying to capitalize on the allegations by offering free coverup and removal work on tattoos done by Boyko.

In the lawsuit, Boyko says that the allegations have made it “almost impossible” for him to work as a tattoo artist, that he has been “blacklisted from visiting tattoo shops nationally” as well as prevented from opening his own shop.

“Due to allegations of rape, potential customers are in fear of being in contact with the Plaintiff,” it adds.

Boyko claims the accusations have also had a profound impact on his mental health, saying since they became public he’s had anxiety, suicidal thoughts, and physical symptoms. He also claims he’s received hate mail telling him to kill himself, along with “derogatory photos.” And it mentions this story, saying that “an individual from a feminist website, jezebel.com” contacted Boyko to request an interview and allow him to explain his side of the story. (It’s true that Jezebel contacted Boyko for comment.)

“The allegations on social media are all anonymous,” Perlman told Jezebel. “A lot of those people are all tagging on to what someone already said. The allegations by themselves are all anonymous, and I think likely orchestrated by Mr. Larson. We haven’t spoken to anybody and nobody’s ever made any allegations to law enforcement whatsoever.” (I told Perlman I had spoken to seven of Boyko’s accusers. He asked me to provide their names. I did not.)

On Instagram a few weeks back, Boyko posted an email that Larson sent him in 2015, apologizing for a previous feud, in which Larson wrote, “I don’t want bad blood with anyone anymore.” Larson says that email was a reference to their argument over Boyko supposedly poaching clients from him, but says he did indeed decide to let it go at the time. “I didn’t want the negativity going around, it feels like a burden to me.”

For Perlman, it’s evidence that the allegations are a professional dispute turned poisonous. “My client’s the only person who’s pursued law enforcement and told them about the situation,” Perlman says. “He’s been proactive. That doesn’t sound like someone who’s guilty of anything.”

As with other industries, some corners of the tattoo world began reckoning with harassment and assault well before this year. A tattoo artist named Ashley Love has been working to bring awareness to sexual assault in tattooing since 2015, and organizes a popular series of fundraising events at tattoo shops across the country called Still Not Asking For It.

Love is 35, and she’s been tattooing for 15 years, currently working out of Yellow Rose Tattoo in Salt Lake City Utah. In an Instagram post from December, she wrote that she was assaulted by a fellow artist during a work trip to Europe, in 2014. She said in the post that while the shop they both worked at swiftly fired him, and while many tattooers expressed sympathy to her privately, plenty of her friends still worked with him and hung out with him socially.

Love says that in her experience, lots of shops simply don’t know how to address harassment allegations. Some shops have liability insurance, which, in theory, can protect against legal claims for things like offensive touching. But many do not: Marisa Kakoulas, a lawyer and tattoo blogger who edits a site called Needles and Sins, says, “So many tattooers have operated outside the law for so long—not paying taxes or employee benefits for example—that finding some structure to deal with harassment claims is not even a consideration for many.”

Plus, handling a claim with sensitivity is a different issue than enacting legal protections or insurance. It comes down to how to adjudicate a delicate and fraught dispute, sometimes between two people who work at the same shop, or between an artist who’s a friend and a client who’s a stranger.

“I definitely do not think tattoo shops know how to handle it,” Ashley Love says. “I think this is an issue across many industries. The world needs education right now. And I mean all of us. I’m not just saying ‘other shops’ or ‘just men’. At this time, we are growing out of a culture which excuses sexual misconduct. The lines have sometimes been unclear and wavering in the past, and now is the time to draw them straight and clear.”

“We are growing out of a culture which excuses sexual misconduct.”

Boyko isn’t the only person in the tattoo world currently facing serious sexual abuse allegations. An anonymous account called Watchdog Tattoo was created in December to field crowd-sourced, anonymous allegations of harassment, assault and rape perpetrated by tattooers. (It, too, named Boyko.) In several cases, reminiscent of the much-discussed Shitty Media Men list, disclosures from one woman prompted a chorus of other women to say that they, too, had been victimized by the same artist.

Facing legal threats, the Watchdog account recently scrubbed their old content and is now only sharing information about artists who have been criminally charged. The anonymous people behind the account did not respond to several messages.

“I have many mixed feelings about that account,” Love tells Jezebel. “The thought of some sort of accurate log of men in my industry with inappropriate behavior sounds great, but i think that’s a much more difficult feat than creating an IG account on a whim. Definitely good intentions behind it, though.”

Love says she’s started to hear discussion about creating a better educational process for tattooers around sexual abuse issues. “Some sort of space for resources, for tattooers to reference & educate themselves,” she says. “Education is what I believe is most important. The effects of sexual assault and rape run very deep, and I really think that many people simply don’t understand this. If we can become a more educated populace, we will create more healthy and supportive allies.”

In the meantime, though, plenty of survivors are still struggling to process their experiences, and social media has played a pivotal role. The Watchdog posts have been validating for women like Anna, who asked to be referred to by her middle name, and who shared an allegation against Nate Click, an Indiana tattooer. At the end of December, she wrote a widely shared Facebook post saying that Click had assaulted her in December 2011, when she came to the shop where he worked after hours to get a tracing of a torso tattoo done. Like Boyko’s accusers, Anna alleges that he had her take off her shirt and bra. (Click didn’t respond to two emails and a Twitter message from Jezebel requesting comment. He recently deleted his Instagram account.)

“He quickly did a tracing of where I wanted the tattoo, and started touching my breasts with his hands and mouth,” Anna wrote. “I was paralyzed and felt on the verge of tears. He said several times very insistently that we should have sex, and I somehow mumbled some excuse for not doing so. I don’t even remember what it was.”

Anna says in the post that Click “physically pushed me down to my knees” and tried to make her perform oral sex or place her hand on his penis.

“The whole time, I wanted to scream, to cry, to run. But I just couldn’t,” she wrote. “I truly thought he was going to hurt me, so I froze and just allowed it all to happen. He eventually finished on my hand, told me to clean up and get out. Said to text him the next day to set up an appointment.”

She didn’t, and says she tried to put the incident out of her mind for years. “I never went to the police because I never specifically said ‘No’ at the time, and I did not think anything would happen if I reported it,” she told Jezebel. “I felt embarrassed that I had been ‘stupid’ enough to go into a dark shop with him, and felt like it was my own fault for walking into the situation.” But, she adds, “I also always felt horrible guilt over it, because I knew in my heart that he had to be doing this to other people, and my not going to the cops or to his employers allowed him to abuse dozens more after me. I still feel this guilt. It has kept me awake at night, feeling like I’ve betrayed people that I don’t even know.”

“I felt embarrassed that I had been ‘stupid’ enough to go into a dark shop with him, and felt like it was my own fault for walking into the situation.”

She stewed over what had happened for six years, Anna says, until she learned about the Watchdog account and saw a post naming Click.

“It literally felt like a weight had lifted off me,” she says. “There were people coming forward and while it hurts to know that numerous other people had been assaulted, it felt good to know that I was not alone and that I had been right in my assumption that he was a predator.”

But Anna says she was frustrated when Watchdog scrubbed their account, including posts that had named Click.

“The Watchdog account made it apparent to me that the rumors I had heard were true and that many, many other women had probably been taken advantage of by him,” she told Jezebel. “I needed my voice to be heard, so I wanted them to have a chance to have theirs heard as well.” So she wrote her Facebook post, and made it public. It’s been shared over 1,000 times, and she says that she’s heard from women who say they had abusive experiences with Click going back as far as 2000.

Black Anvil Tattoo, which Click used to co-own, issued a statement in early January that didn’t explicitly name him, but which confirmed that a “former partner of theirs” had been asked to leave the shop over a year ago for “alleged infractions.”

Dusty Neal, Black Anvil’s co-owner, called the women coming forward to share their stories “brave,” adding that the details had been sobering. “My employees and myself are now realizing that our former partner’s alleged actions were far wider-reaching and much, much worse than we ever knew or could have assumed.” He added that the shop took “immediate action” after a complaint was made, writing, “This has been a learning experience for the members of the shop and myself, and has made us desire being proactive in spotting this type of behavior within our industry and within our own lives.” (Black Anvil didn’t respond to a request for comment from Jezebel.)

“As far as his tattooing business, I hope he never tattoos again,” Anna says bluntly. “Tattoo artists are in a position of power. If you went to the doctor, you would feel safe to sit in their office alone with them because they are professionals and they act accordingly, even if private parts of the body are exposed. A tattoo artist needs to be the same way.”

Tattoos have a rich history as markers of survival and endurance; that’s especially true for women and gender non-conforming people, whose bodies are so often the site of trauma, and for whom there can be a special power in reclaiming and transforming one’s physical self. Margot Mifflin, the tattoo historian, says that her research shows survivors of sexual abuse have used tattoos as a processing and healing mechanism since at least the 1980s “and probably much earlier.”

Anna says she’d originally wanted a tattoo to mark the end of a painful chapter in her life: a devastating breakup had been followed by a prolonged period of mental turmoil, and she wanted a reminder that “I was strong enough to get through it,”as she puts it.

“It’s a way of reasserting control and making the body yours again,” Mifflin says. “Writing over the transgression.” She also found a growing number of tattooers who work to cover physical scars left by domestic abuse, sexual assault and trafficking, people who have been “shot, burned, cut, or to cover up tattoos that were forcibly done on them. The idea is to transform the mark that remains as a reminder of the trauma.” (The same is true of breast cancer survivors who cover the mastectomy scars with tattoos, an increasingly popular practice).

“[Tattooing is] a way of reasserting control and making the body yours again”

That means there’s a particular and searing violation in visiting an artist to get a mark of strength inked on you, only to have the artist victimize you. When Anna was finally able to complete the tattoo she’d wanted from Click, years later, she wept.

“At first, it was hard to get over the fear of another artist taking advantage of me,” she says. “I was terrified to expose any of my body to an artist, and once I did, I was nervous the entire time.”

“I had gone through so much to get that tattoo done, and it had meant so much to me,” she adds. “It was cathartic to finally have it done, and he had done it with such respect.”

Women tattoo artists are leading the larger discussion around harassment in tattooing. In some cases, they’re also dealing with their own experiences of sexual misconduct and harassment. A tattooer named Lydia Kinsey Hunt, who works at Walk the Line Tattoo Co. in Athens, Georgia, created a sort of advisory post I saw numerous tattoo artists sharing on Instagram for weeks. Among other things, she wrote, “You NEVER need to undress more than necessary for the tattooer to do their job.”

Kinsey Hunt tells Jezebel, “I made it to help the women in my life avoid bad situations and know their feelings are valid. Tattooers are considered professionals, so it’s hard for someone that is not in the industry to tell when something is inappropriate or acceptable behavior.”

Kinsey Hunt has herself been subject to inappropriate behavior more times than she can count; she says. A few days before she made the post above, she made one informing male clients that she’d tack on $20 to their bill if they made a joke or asked a gross, suggestive “question” about getting a dick tattoo from her.

“I can’t count the amount of times customers have come into the shop and said something to me on the lines of ‘No, I want to talk to a tattooer,” she says. “Or men usually getting their first tattoos asking me about tattooing their penis, even though they have no actual interest in doing so. They just want to hear me talk about their penis and attempt to make me uncomfortable. I’ve heard of men exposing themselves to female tattooers, messaging them crude things and so on. But as we all know, that behavior is not isolated to the tattoo industry alone.”

Kinsey Hunt says there’s no doubt #MeToo is being felt in the tattoo world.

“I think there’s a new conversation happening in general and what’s happening in the tattoo industry is just a branch of that,” she says. “Women are starting to be believed, so there less of a fear of coming out. It’s not perfect, we’re not done yet. But it’s a nudge in the right direction.”

Several tattoo artists I know told me that the allegations against Boyko are the talk of the insular and tight-knit tattoo world. Yet many tattoo shops were Boyko worked or guest-spotted haven’t commented on the accusations.

A few, however, have publicly apologized. Dave Halsey of Crying Heart Tattoo in Cincinnati wrote a long Instagram post in December that began, “At this point I consider Alex Boyko to be a sexual terrorist. I hope it goes without question that he is no longer welcome at Crying Heart Tattoo. I also hope it goes without saying that we do not condone or support the behavior and actions that have led us to this point in the first place.” Another shop where he’d worked, Chicago’s Black Oak, said they were committed to being a safe space, adding “No one is to ever feel taken advantage of within our doors.”

A number of tattoo artists and shops are pledging publicly not to tolerate assault, and apologizing for instances where they allowed an alleged abuser to work there. And the same women who made stories about Boyko public are now sharing resources on recovering from sexual assault, as well as spreading the word about artists who will cover up or alter his work for free.

In the past few weeks, Lauren, the Detroit activist who made the Facebook post about Boyko, along with her friends has created a massive Google document for sexual abuse survivors that they’ve shared with women who reached out to them about Boyko. It includes listings for therapists doing both individual and group work, legal resources, and numbers for national hotlines. It also lists the names of seven artists who have said they will do coverups, re-works, and blackouts of Boyko tattoos, for women who are uncomfortable having his designs on their bodies.

MW, the woman who says Boyko put a design on her arm that she didn’t want, plans to have the design blacked out entirely. It’s so large and filled with so much black ink already, she says, that it’d be virtually impossible to cover, and anyway, as she puts it, “I don’t want to see it anymore.”

Other, less visible marks are going to be harder to scrub.

“He honestly ruined getting tattooed by somebody I don’t know for me,” MW says. “I’m like, this person already did this to me. What if it happens again?”

Elise, the woman who says Boyko tried to make her touch his penis during an appointment, had gotten tattooed numerous times before meeting him. In the four years since, she hasn’t gotten any new work. She recently moved to a new city, and says she’s nervous about finding a new artist she feels safe around.

“I’m just kind of scared to go to somebody else now,” she says. “Because what if? You never know.”

*Editor’s Note: In the interest of protecting the privacy of a source, some information has been removed from this paragraph.

This story was produced by Gizmodo Media Group’s Special Projects Desk. Email senior reporter Anna Merlan at [email protected].

GET JEZEBEL RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Still here. Still without airbrushing. Still with teeth.