Image: Benjamin Currie/GO Media

“So she cut off his pinga with a machete?”

Yes!

“Ave Maria. Well, I would have done the same thing also; men have no respect sometimes.”

I exploded into laughter as my companions shared the local town gossip while I listened, completely enthralled. The topic at hand was philandering men and unforgiving women. We were sitting inside a door frame that offered some protection from the equatorial sun positioned directly above us, our backs pressed against the delicious cool of the brick walls. It was the kind of scorching heat that turns distant landscapes into blurry, shimmering mirages. To my left was a middle-aged Afro-Brazilian woman who had stopped by to take a sip of water and catch up with the elderly woman between us, the one I had also traveled to see.

Three black women were engaged in conversation, our hands suspended in various positions of expressive dialogue; our heads bowed towards one another. One was wearing a floral headwrap, the other had her hair tied in a low ponytail, and another had box braids tucked under a snapback worn backward. The woman with the head wrap was the toastmaster, an Afro-Indigenous artist who had delivered the punchline, and whose dark skin was speckled with tiny black freckles. Her name is Dona Cadu and, at 99 years old (her birthday was in April), she is most likely one of the oldest ceramistas in Brazil, and one of the most important. I had traveled from Salvador to meet this woman whose pottery can be found in homes, terreiros, and artisanal stores along Brazil’s Northern coast.

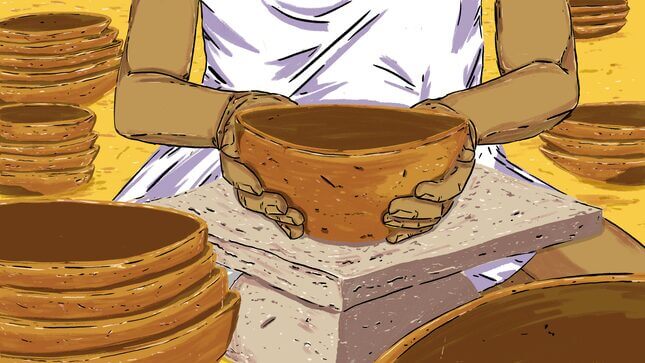

I first heard of Dona Cadu two years ago from a store owner in Salvador who sold earthenware for Candomblé ceremonies—Afro-Brazilian spiritual celebrations with music, dance, food, and communion with orixas (spirits). Her name is familiar across the cultural landscape of Brazil, and her work has been prominently featured at art fairs across the country. Last year she was the subject of the documentary Recôncavo Baiano, which premiered in France at the Connaissance du Monde film conference, where 200 of her pieces were also auctioned. In Brazil, she is best known for her large clay bowls which are used to make popular dishes that require hours of simmering over an open fire, foods like moqueca, a seafood stew. Her bowls are also used to carry offerings for orixas and to decorate homes, being both striking and utilitarian. Sometimes she will smooth the rim with a round pebble and then polish to add a glossy sheen, but more often she leaves the visible ridges as proof of human touch.

About four hours before this afternoon exchange, I had been standing opposite a rundown gas station waiting for a bus. Dona Cadu lives in the small town of Coqueiros, God’s own little acre, with a name that translates to coconut trees. I had to take a three-hour bus ride from Salvador to the municipality of Sao Felix, which is how I ended up in front of the gas station. The two and a half hour wait for the second bus was pointless and I ended up taking a car share on a 30-minute ride through densely wooded hills and pastoral scenery. I wasn’t sure of her address but when I gave the driver her name, he immediately knew where to take me. “Dona Cadu is very famous, heh?” he responded. I nodded as my chapped lips and parched throat cursed me for not bringing water.

When he dropped me off in front of a garage, a woman came to meet me at the door, smiling and unsurprised by the arrival of an uninvited guest. She beckoned me inside and after exchanging “Bom dias” and “How are yous?” I asked if Dona Cadu was home. She gestured towards her left where I saw a small woman sitting cross-legged on the floor. She took up such little space that my eyes missed her at first. She was surrounded by dry, shallow, clay bowls and working on another one. She looked up at me, her eyes kind, curious and welcoming.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-