Image: Array

It is about two hours into my afternoon with David Oks and Henry Williams, the teenagers who persuaded former Senator Mike Gravel to run for president at the age of 88, when Oks, who is 18, mentions that he has a personal assistant who is helping him handle his emails on a volunteer basis. “He’s a high school freshman. Fourteen? Fifteen?” Oks guesses. “A bit of a protégé,” Williams, who is also 18, adds. “David was my protégé, and this kid is his protégé.”

“He is very, very efficient,” Oks says of Clyde, who I soon realize I traded emails with while arranging this interview. That a teenager is fielding press inquiries for slightly older teenagers is just one face of the general weirdness of a presidential campaign run by very young, very online leftists, which is also the reason you’ve maybe already heard about Oks and Williams: two well-read teenagers from the suburbs of New York who heard about Gravel on an episode of “Chapo Trap House,” found his contact information, and successfully drafted him out of retirement to run for president in what is ultimately more of a conceptual exercise about left-wing political horizons than a serious campaign. (Gravel, for his part, says he is a happy participant: “They asked me if it was okay, I said they could do what they wanted, as long as they were doing it and not me,” he told Politico in March.)

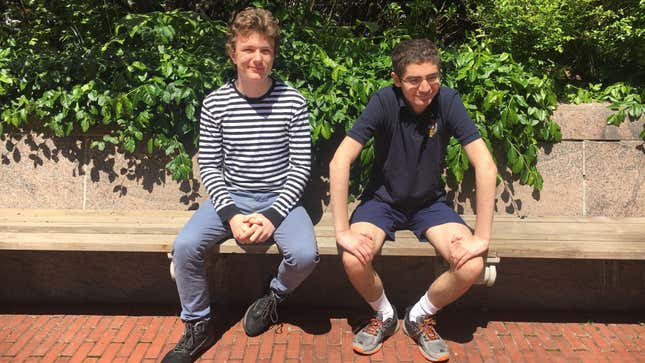

I met with Oks and Williams in early May, first at a deli near Columbia University, where Williams just completed his freshman year, and then on campus after the lunch hour rush proved too noisy for my phone recorder. “Most campaigns are not about the candidate winning,” Williams says in between bites of his bagel in a mostly empty student lounge, where a group of cafeteria workers who seem very good at tuning out student conversations are on break. “But by most metrics, we’re doing better than Seth Moulton,” Oks adds.

The Gravel 2020 strategy is a combination of policy positions culled from movements across the left (the conceptual Gravel is the only full-throated anti-imperialist in the primary, and the only candidate to support a repeal of FOSTA-SESTA and the decriminalization of sex work); mean tweets (“Joe Biden’s a bum. A right-wing chauvinist, good time prick, arrogant bastard creep who thinks that because he’s got a $3,000 suit and the cachet of a lifetime sinecure in the Senate we should bow down to his beaming smile,” a recent example reads); and something like a bizarro, very small-time version of the Lis Smith-crafted media blitz behind Pete Buttigieg.

The whole thing is a gleeful political Matryoshka doll: Gravel 2020 is Mike Gravel, the former senator from Alaska whose political tenure includes reading the Pentagon Papers into the congressional record and running as an anti-war candidate in the 2008 Democratic primary; but it is also—and mostly—Oks and Williams, who are also a few dozen volunteers on staff in their 20s and 30s with experience around policy papers, ad-buy strategy, and the financial paperwork involved in managing a campaign. “You know in terms of the day to day, we have a lot of people just churning away at a lot of stuff,” Williams says. “Contacting press outlets, contacting pollsters, putting together graphics packages, and running the Instagram, the Facebook. They do advertising.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-