The Familiar Despair of E. Jean Carroll's Testimony

Latest

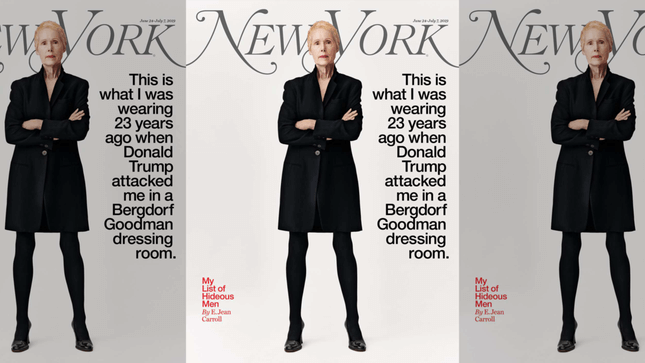

The essay that writer E. Jean Carroll published in New York last week was designed, with every muster of magazine bona fides, to mark an event. From the cover—a picture of Carroll in the coat she says she was wearing when Donald Trump, then real estate tycoon now president, allegedly raped her in the dressing room at Bergdorf; a design that harkens purposefully to another tale of political power run amok—to the near constant churn of follow-ups, press releases, and analysis the magazine has been spitting onto the site since the piece published.

Yet the most powerful trick is a rhetorical one: the very construction of Carroll’s essay, an excerpt from her forthcoming book What Do We Need Men For, uses her copious writing gifts and a powerful narrative structure to ensure that both subject and story made a case for their own accuracy. The setup buries its lead only to resurrect it as a punchline; Carroll writes of the alleged assault with specific, rigorous detail only after anticipating the arguments against her and meeting them with a defense. (She refers to these arguments, crushingly, as her “great handicaps.”) Carroll joins a group of least 15 women who have accused the president of sexual assault, a roster whose names she lists.

Carroll writes of the alleged assault with specific, rigorous detail only after anticipating the arguments against her and meeting them with a defense.

The evidence is laid out gingerly; it is, after all, a 6000-word essay that uses the word “rape” only four times, just twice in reference to Trump, passively spoken by a friend whose words, the magazine is quick to disclose, have been fact-checked. (The line: “‘He raped you,’” she kept repeating when I called her. “‘He raped you.’”)

Where were the sales clerks? Why is there no video recording? Why didn’t she report? Carroll foresees these critiques and prostrates herself to them. That such incidents rarely manifest themselves in perfect terms, that perhaps if there had been witnesses an attacker might have behaved differently, that a video can be a flawed way of capturing sexual violence, that the 50-some years of such violence chronicled in the bulk of Carroll’s essay might ingrain in a person a sense of futility, a lesson in powerlessness. Such arguments are both reasonable and obvious; that she knows she must make them is wrenching.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-