The Complicated and Chaotic History of Kissing Under the Mistletoe

A closer look at the greenery responsible for sleazy dudes scoring winter kisses and 18th-century wives getting to smooch someone other than their husbands.

In DepthIn Depth

Illustration: Vicky Leta

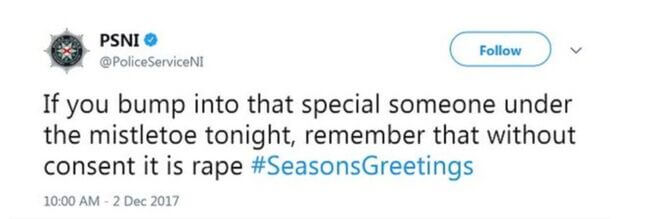

In the winter of 2017, an Irish police department became the main character on Twitter after posting a warning: “If you bump into that special someone under the mistletoe tonight, remember that without consent it is rape.” Replies varied across a spectrum of outrage: Some were furious that the department seemed to be trivializing rape by comparing it to a Christmas tradition. Others laughed, asking things along the lines of, “Are people having sex under mistletoe now?” And some thought the department was being “preachy” and “condescending” by insinuating that people who find themselves under mistletoe wouldn’t know any better than to ask for consent.

Haters will never pass up an opportunity to finger-wag, but the police department was actually more justified than anyone could have imagined. These days, mistletoe is part of the fabric of the holiday season—but there’s no harm in pulling at those strings to see what might unfurl. Maybe, what really struck a nerve about the cops’ tweet was how it dared to acknowledge how many of our traditions—whether for the holidays or not—have an underlying history in coercion and have been widely wielded to disempower women and femmes. Charles Dickens never wrote about anyone getting assaulted under the mistletoe, but tales of the holiday parasite (which usually feeds off the nutrients of living trees and shrubs) do reveal how its 18th-century British origins shook things up in the snogging department.

They eventually took the tweet down but stood by their original sentiment: “We posted a message on Twitter yesterday that some may have taken out of context but the message remains the same; when you are out socialising over the Christmas period, please remember without consent it is rape.” Tarana Burke’s #MeToo movement had just begun to gain traction that year, with stories of nonconsensual sexual experiences coming to the fore—perhaps this was the police department’s way of meeting the moment (I mean…far more police departments did far less). Was it right to categorize something as innocuous as a mistletoe kiss within the realm of sexual assault, or did the unit make asses of themselves?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-