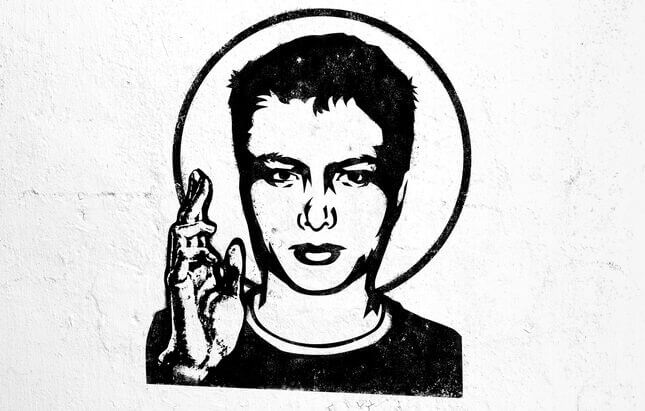

Saint Elliot Rodger and the 'Incels' Who Canonize Him

Latest

Illustration: Jim Cooke

Alek Minassian cited Elliot Rodger as a kind of hero before he drove a rented van onto a busy Toronto sidewalk, killing 10 people on Monday. “All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!” Minassian wrote in a now-deleted Facebook post.

Nearly four years before, on May 23, 2014, Rodger began his “Day of Retribution,” as he called it, killing six people, and injuring another 14. He began by killing his roommates and one of their friends in a shared apartment in Isla Vista, California, before hopping in his BMW and driving to a Starbucks. After he finished his coffee, Rodger began what he described in his self-made video detailing his motives as the “Second Phase…my War on Women.” “I will punish all females for the crime of depriving me of sex,” he said in the video, posted to YouTube while he was at Starbucks. “They have starved me of sex for my entire youth, and gave that pleasure to other men.” So he drove to the Alpha Phi sorority house off UC Santa Barbara’s campus because, while he couldn’t kill “every single female on earth,” he could “attack the very girls who represent everything I hate in the female gender: The hottest sorority of UCSB.” After discovering through “extensive research” that the “most beautiful girls” were Alpha Phis, Rodger decided that the women in the house were his ideal targets. He walked up to the house and knocked on the door, waiting for a beautiful girl to answer. When no one did, he satisfied his need for punishment by murdering two Delta Delta Deltas, Katherine Cooper and Veronika Weiss, who happened to be walking on the lawn near the Alpha Phi house.

The singular act of doling out verdict and sentence is a total restoration of a fantastical hierarchy of gender.

This attack was a source of inspiration to Minassian in the Toronto murders, although police have yet to determine a motive. Toronto Police Services Det. Sgt. Graham Gibson declined to elaborate in a recent news conference, but he confirmed that Minassian “predominantly” killed and injured women. And it’s clear too, even from his brief Facebook posting, that Minassian (who, it appears, posted in “incel” forums—online communities of self-identified “involuntary celibates”) was preparing for Rodger-inspired violence.

“The Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys!,” Minassian added in his Facebook post, referencing incels who, like Minassian, hailed Rodger as a saint, referring to him as Saint Elliot in online forums. As numerous outlets have reported, Minassian’s language is incel in-speak for those who have wronged them. MSNBC reports that “ ‘Chads’ are incel-speak for good-looking men, who incels believe can’t be one of them. ‘Stacys’ are the women who find ‘Chads’ attractive.”

His ideology—if such grievances are even coherent enough to be termed an ideology—resembles Rodger’s worldview: one of the aggrieved men; men who believe that they have been victimized by shallow, petty women who refuse to have sex with men like them. Destruction here is not just revenge, it is not just punishment, but it is a misogynist’s right: The singular act of doling out verdict and sentence, of enacting a grotesque kind of justice, is a total restoration of a fantastical hierarchy of gender. There is perhaps nothing more potent for the aggrieved followers of Rodger than acting as judge, jury, and executioner for any and all women.

Entitlement to any woman of his choosing was, by all accounts of successful American masculinity, Elliot Rodger’s rightful inheritance. The son of a successful filmmaker, he was raised with all of the material goods that should signify potency, but Rodger’s hyperbolic perception of masculine success combined with his overblown sense of self (he describes himself as a “magnificent gentleman”) turned out to be deadly instead of a comical fantasy of masculine authority. Rodger’s spree would kill one more, another UCSB student Christopher Michaels-Martinez, and injure 14 before Rodger crashed at an intersection and eventually shot himself in the head.

With Rodger dead in what Sarah Nicole Prickett called a “virgin suicide,” his legacy—if such actions are even coherent enough to be called such a thing—wasn’t just the six people he murdered, but the anger that stemmed from those murders and his misogyny.

Rodger’s BMW has been traced by his followers, its location documented online, like a perverse relic.

On message boards where incels like Rodger gathered, he wasn’t just a martyr, he was hailed a saint. May 23 marked “St. Elliot’s Day.” “May he rest in peace,” one incel wrote in a now-deleted 2017 Reddit thread. “Let us not be sad. Today is a day to celebrate… the retribution.” Another called Rodger a “sweet prince.”

The language is stilted and almost overtly religious; the demand to rejoice, to celebrate the “retribution.” It’s the overburdened language of church, so formal that it can only conjure up sacred grounds, and holy people. But then Rodger’s own death was (perhaps purposefully) overdetermined with such religious overtones. The symbols accumulate easily: the virgin death, the shedding of his own blood, the memoir-manifesto that read either like a self-authored hagiography or the delusional rant of a failed authoritarian.

To the women who hashtagged abuse and misogyny in the follow-up wave of #YesAllWomen, My Twisted World—Rodger’s 141-page disjointed pastiche of manifesto and memoir laying out a series of demands that constituted what he believed to be the kind of natural right of a “superior” “alpha male” like himself: hot blondes, flashy cars, money, and invitations to exclusive parties—was evidence. But I have a sneaking suspicion that, to the choir at least, it was a coherent statement of purpose; the “Day of Retribution,” an ideology turned into action. #NotAllMen was said with such purpose, with such conviction, that it seemed more like a recitation than any attempt at persuasion or rebuttal. Even Rodger’s BMW, the one material object he possessed that reflected his valued aesthetic, has been traced by his followers, its location documented online like a perverse relic.

Transformed from the Isla Vista mass shooter, the incarnate of deadly misogyny, and into Saint Elliot, it’s no surprise that he would be venerated. A saint’s purpose is often his own destruction, to act as either revelation or instruction: Rodger’s final act was the punishment of those who had wronged him. Stripped of what he viewed as his innate authority and the spoils that should have followed that authority—sex, women, importance—Rodger enacted it in death, claiming bodies and ultimately lives, brutally linking his name with hot sorority girls in eternity.

The death of a saint is the destruction of beauty: What’s mourned is the loss of that beauty—both physical and spiritual—it’s perhaps why some of the most brutally murdered saints are women, conjuring up a cultural sympathy that’s usually reserved for such ideal women. It’s why the pantheon of saints is filled with women who hold their severed body parts, hold their instruments of destruction, as they look lovingly on eager worshippers seeking intercession. The blond sorority girls who Rodger wanted to murder usually conjure up sympathy: They are the ideal dead girl, their destruction is irresistible. Rodger’s sainthood is a reversal of such values; destruction is celebrated and destruction is redemption.

men like Minassian didn’t have to look hard to find inspiration, heroes, or growing examples of how to carry out deeply gendered violence.

That redemption continues to find a following. Minassian was not the only mass murderer who found inspiration in Rodger. Parkland shooter Nikolas Cruz, who killed 17 students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas in February, reportedly expressed admiration for Rodger. “Elliot rodger will not be forgotten,” he wrote in a comment on a YouTube video about My Twisted World. Though Cruz doesn’t appear to have frequented incel chatrooms, on the website incel.me posters have spent a great deal of time deconstructing Cruz, debating whether or not he qualifies as an incel. Maybe he was, maybe he had an “incel-tier” girlfriend, or maybe he was just a “failed normie,” or maybe he was an incel “cucked” by his ex-girlfriend. The semantics are so personal, the language so overtly racist, invisible wounds so nursed, that it’s difficult to draw any insight other than victimhood, engendered solely by women exercising autonomous choices.

While some are quick to point out that Cruz was no incel saint, and veneration should be reserved for true heroes like Rodger, they are equally quick to point to the real incel saints who remain underappreciated. Killers like “Saint Cho,” a reference to Seung-Hui Cho, who murdered 32 and wounded 17 at Virginia Tech and George Sodini, who, in 2009, murdered three women and injured another nine during a workout class in a Pittsburgh-area LA Fitness.

If Rodger is the patron saint of incels, Sodini is a minor saint. Hailed as the “OG incel” on Braincel, a Reddit forum for incels rife with racism and sexism, Sodini’s 2008-2009 diary recounted with a bitter tone all of those who wronged him, from family members to the “30 million women rejected me – over an 18 or 25-year period.”

“Thirty million is my rough guesstimate of how many desirable single women there are,” Sodini wrote. “A man needs a woman for confidence. He gets a boost on the job, career, with other men, and everywhere else when he knows inside he has someone to spend the night with and who is also a friend. This type of life I see is a closed world with me specifically and totally excluded. Every other guy does this successfully to a degree.” He wrote of his loneliness, comparing it to the Holocaust. He sketchily outlined his plan to murder women at the gym. His first attempt unsuccessful (“I chickened out!…brought the loaded guns, everything. Hell!”) he practices, works out the details, to ensure the success of his “one shot.” After the diary ended, Sodini walked into a dance class and opened fire. He killed three women—like Rodger, women he had never met, never spoken to—Heidi Overmier, Elizabeth Gannon, and Jody Billingsley.

These “saints” are pervading

These “saints” are pervading and men like Minassian didn’t have to look hard to find inspiration, heroes, or growing examples of how to carry out deeply gendered violence. Rodger had been transformed into a saint, venerated by a community of men who thrive on misogyny and violence, but even without them to preserve his memory and celebrate his memory, there would still be a Rodger, or a Sodini, or even a Marc Lépine. There will always, too, be men willing to venerate them for murdering women simply because they are women. Rodger wanted to discipline hot sorority girls; Sodini wanted to punish any of the 30 million women who he believed had wronged him, and Lépine, who murdered 14 women at the École Polytechnique in Montreal, was “fighting feminism.” While they killed individual women—19 between them—they weren’t interested in the actual women they murdered, but rather the ideas and defiances of traditional gender norms they believed them to represent.

Their victims were stand-ins for abstractions, for women who had erred by not submitting to some natural order, some hierarchy of gender meant to be determined by these men alone, meant to satisfy their needs. They were killing an idea, but ideas are not flesh and blood, and they are impossible to kill. The same could be said for “saints” like Elliot Rodger.