Ruth Wilson Gilmore Says Freedom Is a Physical Place—But Can We Find It?

Everything seems awful right now. But the author of Abolition Geography insists that "without optimism," there’s "no point in bothering."

BooksEntertainment

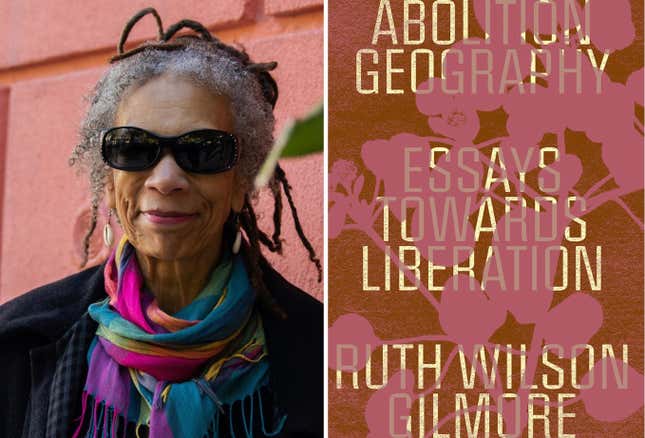

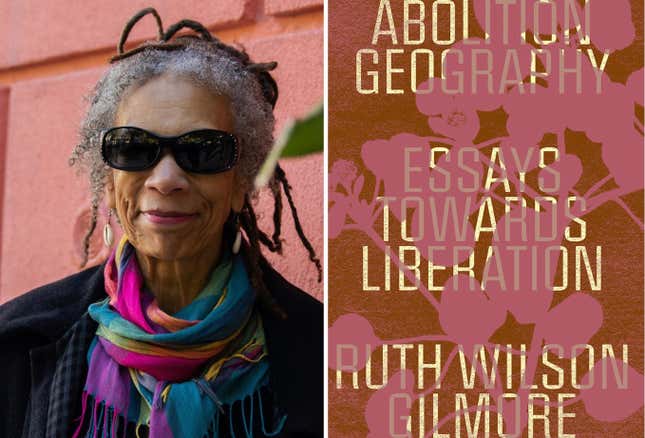

The year before support for prison and police abolition exploded into the mainstream in the summer of 2020, the New York Times Magazine ran a profile of scholar-activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore titled: “Is Prison Necessary? Ruth Wilson Gilmore Might Change Your Mind.” That is to say, Gilmore has been at the helm of the movement for abolition—and an authoritative critic of racial capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchal oppression—since long before the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor spurred a global reckoning.

Gilmore, a professor and director of City University of New York’s Center for Place, Culture, and Politics, learned about organizing and struggle from her parents as a child. It was those early lessons, as well as her education and formal training as a geographer, that have informed her activism, teaching, and the numerous books she’s authored or contributed to on building a world beyond prisons, policing, and neoliberal exploitation. Her latest offering? Abolition Geography, a scathing exploration of global systems of oppression through a lens of geography, in which she asserts that freedom and liberation are a physical, tangible place—they’re material conditions, not platitudes and niceties from ultra-rich politicians. The age-old question, of course, is how we get to that physical place.

“‘Freedom is a place’ means we combine resources, ingenuity, and commitment to produce the conditions in which life is precious for all,” Gilmore told Jezebel over Zoom. “So, no matter the struggle, freedom is happening somewhere. Through different forces and relations to power, the people are constantly figuring out how to shift, how to build, how to consolidate the capacity for people to flourish, to mobilize our communities, and stay in motion until satisfied.”

In a conversation with Jezebel about her new book, Gilmore maps out what a path forward rooted in abolition looks like, and how to get to that physical place of freedom. In the wake of the Uvalde, Texas, shooting and the police failure that enabled it; ahead of a Supreme Court decision expected to reverse Roe v. Wade; and following the chilling backlash against sexual assault survivors we witnessed in the recent Amber Heard-Johnny Depp defamation trial, Gilmore also explains how each of these devastating political moments could be addressed by abolitionist principles—the “place of liberation” we collectively build must be safe and nurturing for all.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ahead of the Supreme Court’s looming abortion rights decision, how is the decimation of reproductive rights conjoined with the movement for abolition?

So, let’s stop and think for a second about physical reality, that in our embodiment as living beings, we are space and time—I am, you are, whoever is reading this interview is space and time. That’s a given—we are not an abstract theory. This dreadful example about Roe is grounded in what that fact consists of socially, spiritually, politically, and viscerally all of those ways. So as Dr. Angela Yvonne Davis teaches us, freedom is a constant struggle, and abolition in that struggle is reproductive justice. These aren’t separable movements. The capacity to flourish inter-generationally—whether that means to bear children, or not to have children, makes no difference—reproductive justice is abolition.

You write about the systematic ways that oppressive systems and institutions are shortening people’s life spans, killing them across lines of race, class, and identity. What can we take away about whose lives are and aren’t valued in this country? How would abolition address this?

I think the principal takeaway we have right now is that in the U.S., the forces of organized violence, principally the police, are better organized to seize any moment. Police can count on people expecting them to be the solution, and to always be able to demand more resources to fulfill that expectation. And this is the problem. The defund [the police] movement seeks to address this as part of the greater abolition movement, and more broadly, we know about group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-