Remembering Larry Kramer, Champion and Adversary of Humanity

Latest

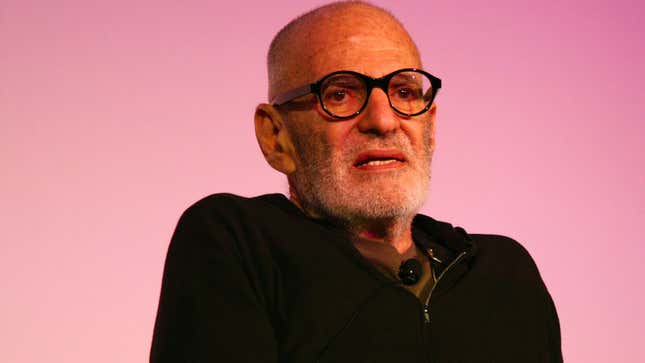

Image: Getty

Gay history is the dominion of gay people. We create it, obviously, but more importantly, we maintain it. As long as LGBTQ history remains unsung and under-taught, it is abundantly clear that we must tell our own stories and show why they are important, in the process creating hero narratives from the stuff of our existence. And Larry Kramer, the gay activist, writer, and provocateur who died of pneumonia Wednesday at age 84, was a master of self-mythology.

His furious energy is what sold it. At least to me. I remember being a young teen knowing that I was gay and not wanting to face it (despite being called a faggot routinely by kids in my school from second grade on) but yearning for some vicarious channel for my anger. I found that Malcolm X could do the trick: His eloquent rage rendered public speaking into art, he was accessible thanks to his widely-read autobiography and the gorgeous Spike Lee movie based on it, and his cause of antiracism was socially acceptable in the early ‘90s in a way that gay rights just couldn’t be for me at the time. I could channel my anger at general inequality into addressing racism specifically.

Even after coming out over a decade later, I held onto Malcolm as the ideal symbol of righteous indignation. The thing about gay history is that if you aren’t actively seeking it out, there’s a good chance you might not learn it. It wasn’t until I saw David France’s 2012 documentary How to Survive a Plague that I felt what I guess you could call my velvet rage reflected back at me onscreen by Larry Kramer.

I still think about this scene all the time, how Kramer could fiercely cut through all of the bickering bullshit in a room of activists and shift the focus to what truly mattered: The plague. AIDS. Kramer watched his friends, lovers, adversaries, and others drop dead around him and it ignited a fire in him. In a series of articles that eventually filled a book, he chronicled the disease in its earliest days. He loudly took to task the New York Times’ sporadic coverage, as well as President Ronald Regan and New York mayor Ed Koch’s apathy, which allowed the disease to proliferate. Kramer was instrumental in founding the early activist groups the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and then ACT UP, after he was thrown out of the former. Without those groups, made up of enterprising queer people who essentially taught themselves about pharmaceutical science and public health, the crisis might still be as uncontrollable as it was in the early days. We might still be in the “plague years.” The AIDS activists of the ‘80s and ’90s that Kramer helped focus and assemble were instrumental in the discovery and adoption of antiretroviral drugs that today can control HIV to the extent that it functions as chronic condition, and not the death sentence that it was initially known to be. In this endeavor, Larry Kramer was indispensable. Who knows where the epidemic, and for that matter we, would be without him.The emergence of AIDS made Kramer look something like a prophet. His widely read and much maligned 1978 novel Faggots seemed to predict a reckoning gay men would face if they continued their liberation-era promiscuity: The novel’s protagonist Ned, understood to be a thinly veiled stand-in for Kramer himself, begs his nonmonogamous object of desire Dinky to commit “before you fuck yourself to death.” Faggots is a thorny, at times clunky novel, equal parts trashy beach read and profound meditation on connection. In his excellent history of gay literature Eminent Outlaws, writer Christopher Bram says Kramer’s book is “an erotic novel that denounces sex, which is kind of schizophrenic, but sex often turns people nuts. Kramer and his enemies would later claim the book is a uniform denunciation of gay promiscuity, but it actually revels in sexuality.” Bram adds that Faggots sold well—around 350,000 copies—and unsurprisingly, at that. “It gave gay readers the opportunity to feel morally superior to men who got laid more often than they did and to jerk off,” Bram reasons.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-