In ‘Prima Facie,’ a Lawyer Puts Her Own Rape on Trial

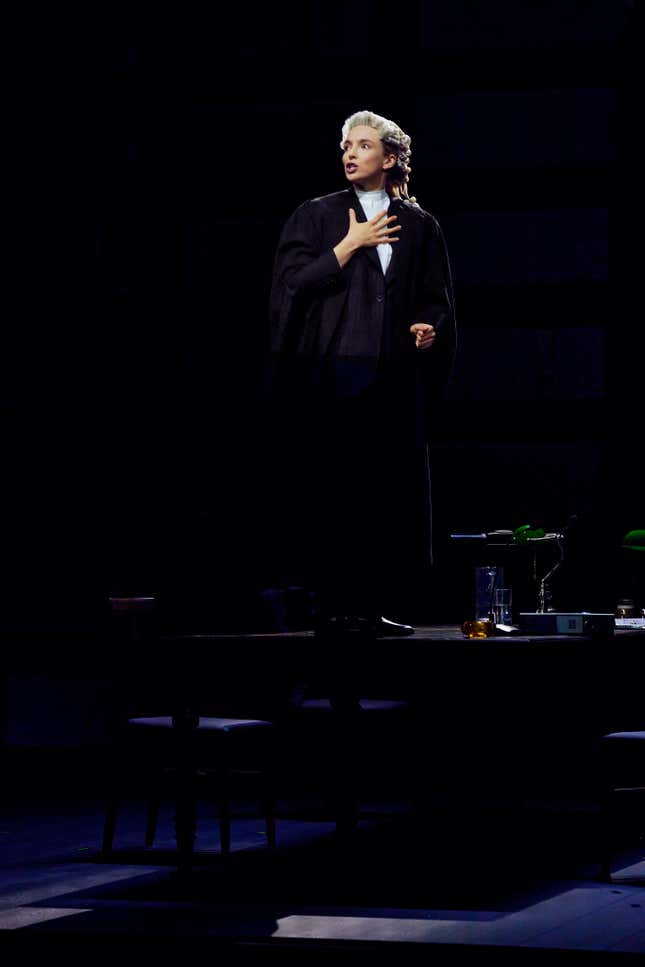

The one-woman play, starring Jodie Comer and currently up for four Tonys, interrogates sexual violence. It also allows survivors to feel everything but OK.

In Depth

There’s a question that awaits every survivor of sexual assault after they confront what’s happened to them. Actually, I know from experience that there are several, from obtuse (did you have too much to drink?) to just plain offensive (why didn’t you fight back?). But more often than not, one that’s somewhat more well-meaning inevitably reveals itself: Don’t you want justice? Such is what the audience is prompted with every performance of Prima Facie, Suzie Miller’s one-woman play that opened on Broadway this spring after an Olivier-winning stint on the West End, and is up for four Tony awards this weekend.

Justice, as protagonist Tessa Ensler finds after she’s raped by a colleague, is elusive. It can’t be earned, and it’s exceptionally individual. In the 100-minute play, Ensler, an esteemed criminal defense attorney for men accused of sexual assault, portrayed without restraint by Jodie Comer, is an avatar for sexual assault survivors—a faction of people Miller is well-acquainted with. Before the Australian playwright found the stage, Miller occupied a different kind of theater as a human rights attorney. For years, she was charged with taking victim statements—at least six per week, but sometimes more—from mostly women and noticed the very patterns Ensler painstakingly unpacks for captive audiences of Prima Facie.

“When I was at law school, I remember thinking that it was really strange that everyone seemed to think it was OK to focus on whether the men believed there was consent rather than whether there was or wasn’t,” Miller recalled in an interview with Jezebel. “Then when I became a lawyer, I took a lot of sexual assault statements from young women, and I was shocked by how consistently similar they all were in terms of the reaction. It was in the days when saying, ‘I froze’ wasn’t seen to be an appropriate response. You had to have a fight-or-flight response in order to prove that you are resisting or rejecting.”

More often than not, something akin to paralysis—a temporary suspension of time, space, and, most damaging of all, logic—takes over. It’s a reaction in survivors that the audience sees Ensler not just interrogate but experience firsthand. Miller was certain that British director Justin Martin would treat it with empathy.

“My problem with the legal system is that my life is as influenced by the women in my life as it is by the men in my life, and the legal system is not, and it should be in order to work for all of us,” Martin told Jezebel. “I think what I hoped to do was to provide a way that I could get into the conversation with men who often look at a play like this and go, ‘Oh, that’s not for me, or it’s hard work, or I’m not going to enjoy myself.’ They’re the people I want to talk to.”

Upon first impression, Ensler is a sharp, sensible, and self-assured legal star with working class roots. She’s swiftly made a name for herself clinching victories for her clients by strategically sowing just enough doubt in survivors’ testimonies. Ensler is proud of this, evidenced early by the way she practically makes a meal of cross-examination. Lawyers are simply storytellers, she reminds us. Just as easily as they can devise their own narrative, they can dismantle another’s. Ensler does both with the arrogance of someone who defines themselves not just by their job, but by the law writ large. Such was Miller’s intention when writing Prima Facie.

“I was thinking, I’ll take one of those really diehard believers, which, of course I was when I started law—I thought, ‘Yeah, the law is about justice’—and then I’ll put them through the process, so they see both sides of it,” she said.

Ensler’s perspective on the other side arrives after she’s sexually assaulted by a colleague, Julian, a little less than halfway through the play. They’d maintained an in-office flirtation, gone on a mutually enjoyed date, and had consensual sex more than once. Ensler’s case, quite bleakly, is anything but black and white, which much of her work has already made her aware of. There are discrepancies to be discovered and dissected should she ever offer herself up to cross-examination, and though Lady Justice is supposedly blind, she’s certainly not deaf. Ensler is faced with a difficult decision: Either she does what the majority of those who survive sexual trauma do and remain silent, scrounge for pieces of peace, and attempt to move forward; or, she presses charges and risks public shame and professional peril.

First, Ensler puts herself on metaphorical trial, examining her every decision. Had she railed hard enough against the roughness of her perpetrator? Why did she take a shower after the assault? Didn’t she know better than to leave her apartment and delete Julian’s text messages? “The restaurant bill indicates there was a lot of sake drunk by you both, witnesses say you were giggling, yes?” she imagines an attorney prompting her. “And there are two empty red wine bottles at your house, wouldn’t you agree?” “You took off most of your clothes, is that right?”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-