On The Internment of My Grandfather

Latest

I remember the exact moment that I connected internment with my family. I was in elementary school, and we had learned all about the New Deal and Franklin Delano Roosevelt in social studies. Later that week, I was at my grandparents’ house for a family dinner, and I was reciting all these things I had learned at school, talking mostly, as I had been taught, about how great FDR was. My grandfather’s sister, an ex-nun we called Auntie Auntie, said, “You know he interned the Japanese, right?”

Over 100,000 people, two-thirds of them American citizens, were forced to leave their homes and jobs, get on trains, and live crammed into hastily erected sheds that weren’t suited to the weather. Their language was banned in the camps. Their children’s schooling was interrupted and subpar. The food made them sick and the hospitals were understaffed. And while they were suffering, they were asked if they would swear an unqualified allegiance to the United States. They were asked if they would serve in America’s military.

All of this was done on the order of a president hallowed by liberals. At the urging of the man who would become the most famous liberal Supreme Court Chief Justice, Earl Warren who was at that time the Attorney General of California. It happened to my family, and none of it is anything to casually invoke as an example of something our nation should do again.

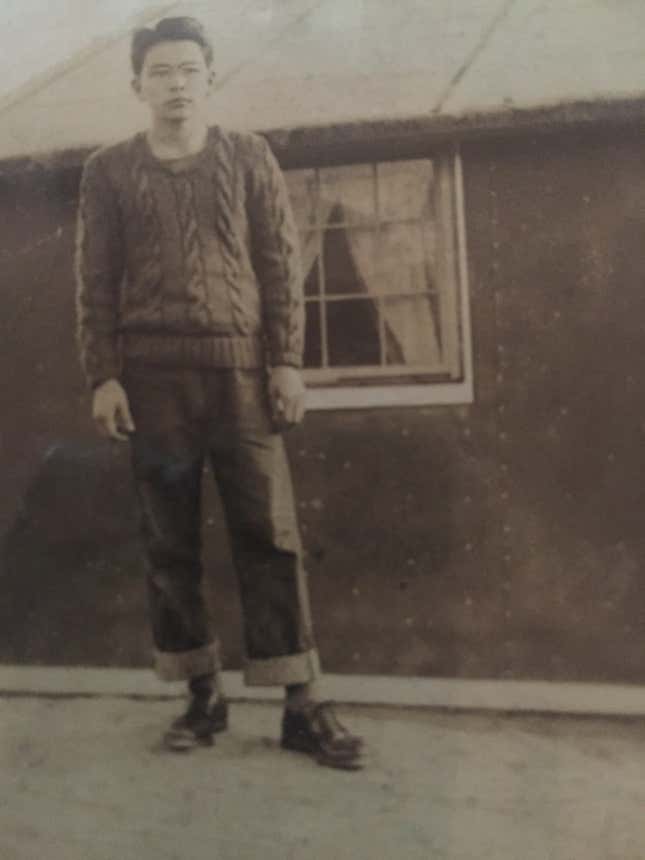

My grandfather, Bill Yamamoto, is 89 now. He was fifteen when he was interned and was seventeen when he left the camp for the army. My grandfather came out of camp, as he puts it, and managed to go to college and get a good, stable job with the federal government, where he worked for most of his life.

My grandfather married my grandmother, who was also interned at a different camp and with whom I share a first initial and only rarely the grace and strength she displays every day. (Last year, she broke her hip and refused painkillers because she didn’t like the dreams they gave her. She did ask for umeboshi, a salt-cured Japanese plum. She also recommends it for morning sickness.) They have three daughters, my mother being the oldest. They have seven grandchildren, who have all reached adulthood as healthy, relatively happy adults. Just last month, they got to watch one of their grandchildren get married.

Week before last, they watched Donald Trump get elected president. Last week, Carl Higbie, the head of Trump-supporting PAC Great America and a Trump surrogate cited internment as a precedent supporting the president-elect’s proposed registry for Muslims. “We did it during World War II with the Japanese,” he said. He added later, “I’m just saying there is precedent for it.”

My grandfather’s response was, “He’s crazy.”

My grandfather’s family bears many scars. My great-grandfather moved to the United States in the hopes of finding a job and making enough money to eventually return to Japan. But when he got back to Japan, he was persecuted there for being a Catholic. So he emigrated back to the United States in order to freely practice his religion. All of his children would be born in California, as American citizens, thanks, of course to the principle of birthright citizenship, which is enshrined in the 14th Amendment. It guarantees that anyone naturalized or born in the United States enjoys all the same rights as any other citizen. It’s been upheld by the Supreme Court as far back as 1898, and it is the reason my grandparents, my mother, and I are Americans. Senator Jeff Sessions, Trump’s pick for attorney general, has spoken out against birthright citizenship.

After Pearl Harbor and the increase of anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States, my great-grandfather was targeted by the FBI. He was never charged with anything or put on trial. But one night, a group from the FBI came to their small house. The FBI parked at a neighbor’s place, and came into my grandfather’s house through all three doors. My great-grandfather was taken into custody from the bathroom, where he had been on the toilet. Other agents searched the house, while my great-grandmother instructed my grandfather and his two sisters to watch them.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-