No Woman Is Ever ‘Asking’ to Be Stalked

A new podcast exploring one woman's harrowing, 13-year journey as a victim of stalking is disrupting popular narratives about stalkers and their victims.

In DepthIn Depth

It started with an email.

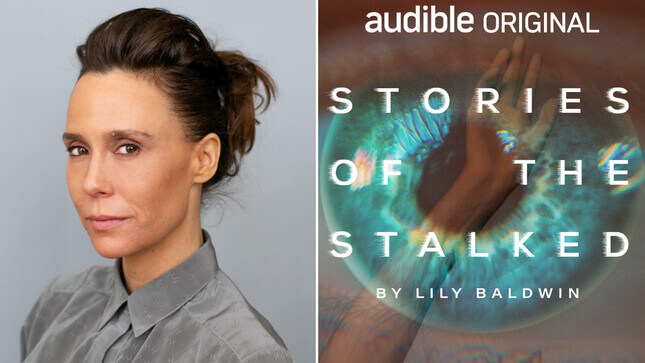

In 2009, when Lily Baldwin was touring the world as David Byrne’s backup dancer, the man who would stalk her for the next 13 years first initiated contact. In the message, her stalker, a British man Baldwin refers to as X, invited her to work with him at a company he was starting. But the email was also laced with unnervingly vivid descriptions of her performance at the David Byrne concert the night before.

Shortly after the first emails, the situation began to spiral. Soon, X was sending Baldwin and her mother disturbing packages with sometimes tender, sometimes angry letters. He’d even send pieces of garbage and personal effects from his day-to-day life. He was leaving her obsessive voicemails, referring to her as his wife, and accusing her of leading him on despite never once interacting with or responding to him. Then, about a year after his first email, X crossed an ocean to be in the same city as her, and when he came to the US again in 2012, this time, she was forced to hide in safe houses in Los Angeles and San Francisco, afraid for her life.

All of this unfolded years before the rise of platforms like Instagram and Snapchat, which encourage people to location-tag their posts and stories at all times—making X’s dedication to stalking her all the more terrifying. Baldwin, a dancer, filmmaker, and writer, has since created the new six-episode Audible podcast Stories of the Stalked, recounting her ongoing experience with stalking in bone-chilling detail. In it, she reflects on the limited protection afforded to her by law enforcement and public policy, as well as the psychological and physiological toll of experiencing stalking. Throughout Stories of the Stalked, Baldwin talks candidly about the struggles of working as a woman in media, and raises intriguing questions in the age of influencers: What is the price of being a woman and actively working in the public eye? And why are women like Baldwin expected to pay this price without complaint? “Visibility is currency,” she observes throughout the podcast. So, what did it cost Baldwin to literally fall off the grid and hide for her life in 2012?

Now, Baldwin tells Jezebel she thinks women working and striving to be in the public eye want the same things we all do. “We want followers—we don’t want to be followed. How do we keep the first happening, but not the second? I’m not interested in advocating people disappear,” she said, noting the “double-edged sword of visibility.”

There are no easy answers or “bite-sized” solutions to this problem, Baldwin told me, but one thing’s for sure: No matter how famous a woman is, no matter how visible her career requires her to be, no one is ever “asking for it” when it comes to stalking. Nor is any stalking victim overreacting. Stalking, like all forms of abuse, is about power and control—and, like any other abusers, perpetrators use fear to exert power over their victims. Anyone, regardless of their career or how many Instagram followers they may have, can be a victim.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-