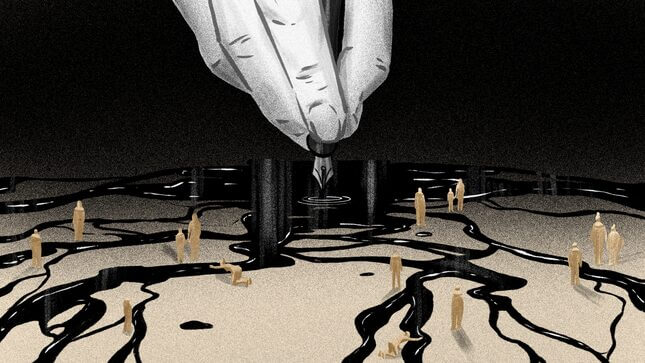

Illustration: Benjamin Currie/GMG

I come from a lineage of bad hombres. My bisabuelo was one of the bad ones—not one of the model Mexicans you’re supposed to care about, the ones whose stories some people cherry-pick to tug at your heartstrings.

Antonio Valenzuela went to prison in 1929 after assaulting a fellow mine laborer with a razor blade when he was drunk. His mug shot shows his hair swept back elegantly with pomade, but lopsided, with some stray strands sticking up. He was deported with a million other Mexicans scapegoated for the Great Depression in the 1930s.

“Get rid of the Mexicans!” cried Americans then. Decades later, in 2015, a reality TV star said Mexico was sending “rapists” and “criminals” to the United States. “We have some bad hombres here and we’re going to get them out,” Donald Trump declared, and I knew he meant men like my great grandfather.

Our country has a long history of deporting, detaining, demonizing and deterring immigrants with death. It didn’t begin with Trump, and it will continue under the Biden administration unless he and the rest of Americans reckon with how the stories of “bad hombres” like Antonio have for decades been weaponized to punish entire immigrant communities. By contrasting “bad hombres” with “good” immigrants who work unnaturally hard and never break any rules, political leaders and media figures reduce immigrant lives to caricatures that can be exploited and expelled.

For example, the Obama administration backed mass deportations of what he called “felons, not families.” Unlike Trump’s family separations, which targeted people asking for refuge at the border, Obama focused on immigrants in the U.S., allegedly serious criminals disembodied from relatives. But all of them had families, and a majority had committed only immigration offenses. Obama deported three million people—a record—and in the process, separated hundreds of thousands of families. During this time, I interviewed deported fathers in the storm drains of northern Mexico as they wept for their lost children, jobs, and homes. Some of those I spoke with used heroin and crack cocaine to cope with the trauma of separation. Many lived in homeless encampments and underground near the border in Tijuana, clinging to the dream of returning to the U.S.

These men were rejected by Americans and Mexicans alike. They belonged nowhere. Some reminded me of my father, an immigrant who struggled with addiction and hallucinations and who I wrote about in my memoir, Crux. I documented their skeletons in desert-smuggling routes and waded through pools of their blood in the morgue. My reports and those of other Latinx journalists, and the situation in general, stirred rage among many progressives and Latinos. But there was no cavalcade of national headlines calling it “torture,” “child abuse,” or a “crime against humanity.” Most Americans simply went on with their lives; the deportees disappeared from their minds. I wondered what it would take to get people to object to the violence of immigration enforcement, which I had been thinking about since reading Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway in 2004 as a high school student. A white editor suggested I find more “relatable” sources.

Finally, in 2018, Americans of all backgrounds began to express horror at the violence of our immigration system. What had changed was not the violence but the general profile of its victims. Rather than flawed men literally ejected from this country—out of sight, out of mind—the victims were parents and children fleeing for their lives and requesting asylum at the Southwest border. Progressive media outlets blasted the sounds and images of crying children and terrified parents across the country. These were clearly not “bad hombres.”

Jacob Soboroff, NBC reporter and author of the national bestseller Separated, became the face of the movement objecting to Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy. He helped spark national outrage about family separations by reporting on innocent children “in cages.” He was late to the story, but he was effective. Within weeks, Trump said he was ending his policy; he “didn’t like the sight or the feeling of families being separated.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-