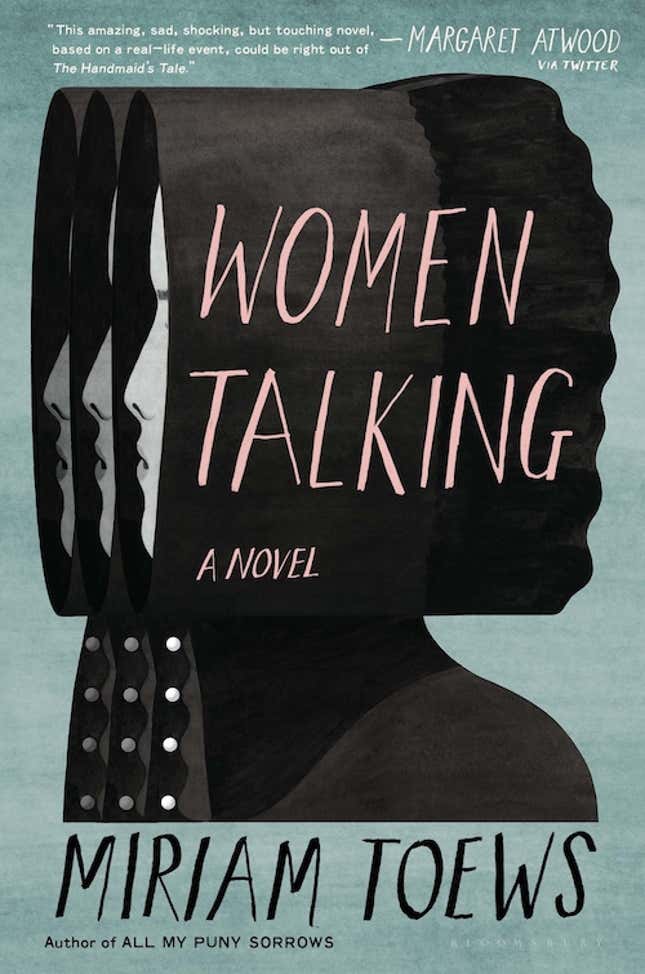

Miriam Toews's Women Talking Explores the Aftermath of Rape in a Remote Mennonite Community

In Depth

The forward to Miriam Toews’s eighth novel, Women Talking, begins with a punch of horrific reality: “Between 2005 and 2009, in a remote Mennonite colony in Bolivia named the Manitoba Colony, after the province in Canada, many girls and women would wake in the morning feeling drowsy and in pain, their bodies bruised and bleeding, having been attacked in the night. The attacks were attributed to ghosts and demons,” Toews writes, continuing, “[…] eventually, it was revealed that eight men from the colony had been using an animal anesthetic to knock their victims unconscious and rape them.”

Toews’s novel explores what the women in these colonies would have talked about after the rapes happened, and more importantly, what imagined action they would take: do nothing, stay and fight, or leave the colony for good. Toews was raised in a small, conservative Mennonite community in Manitoba, Canada, and much of her work focuses on the lives of Mennonites, from the ultraconservative to the secular (Toews herself is a secular Mennonite). “Even if I’m not directly writing about Mennonites, even if that’s not evident in the text, there are still Mennonites in my mind,” she told me by phone last month. Women Talking is the most direct reflection—and by extent, carefully considered condemnation—on the fundamentalist, patriarchal foundations of the religious sect in which she was raised.

Women Talking illuminates Toews’s many talents in tandem: she presents women in a dire and tragic situation but affords them solemnity and introspection. But as she does in her books (she may be the only living writer to write a novel about assisted suicide that will make you sob and laugh), Toews allows generous humor and lightness to pour in. After all, they’re only women talking.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

JEZEBEL: Women Talking has been out in Canada for seven months now. How does it feel to finally have it come out in the States?

MIRIAM TOEWS: There are just so many more Americans than there are Canadians! So in some ways, it’s a similar process, but it’s just amped up a bit. And it’s exciting because it’s an opportunity to connect with more readers.

You’ve been wanting to write this book for a while—the incidents happened in 2009. But you ended up publishing two different books in between (Irma Voth in 2011 and All My Puny Sorrows in 2014). How did you know you were actually ready to write Women Talking?

I had been thinking about these crimes in Bolivia since 2009. Like everybody else, I was horrified but not necessarily shocked, and I felt that I wanted to write about it somehow—I didn’t know how or what exactly. But then my sister got quite sick and in 2010, she committed suicide. I was devastated and I didn’t think that I was ever going to write anything again. But when I did finally want to write again, I wanted to write about my sister and I ended up writing All My Puny Sorrows about her. Irma Voth was already edited and ready to go, and that book came out shortly after my sister died.

I felt a moral obligation to do it as well, a duty to express solidarity with these women

When I was touring on Irma Voth in 2011, I was talking to a lot of people about Bolivia again and what had happened there. First of all, a lot of Mennonites come to my readings, whenever I go on tour, I’m always talking to a lot of Mennonites. I’m talking to a lot of Mennonites regardless [laughs]. People were saying, “You should write about it.” Certainly, I wasn’t alone in thinking about it, especially women within the Mennonite community. We were all—so many of us, men too, of course—trying to come to terms with it, trying to understand it. What on earth could we possibly do? I’m a novelist, so writing a novel seemed to be the thing that I could do, the thing that I needed to do and wanted to do. I felt a moral obligation to do it as well, a duty to express solidarity with these women.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-