Mena Suvari on Surviving Hollywood: The Jezebel Interview

In an interview, the actor opens up about her new MeToo-inspired memoir, The Great Peace, and the abuse she writes about surviving

BooksEntertainment

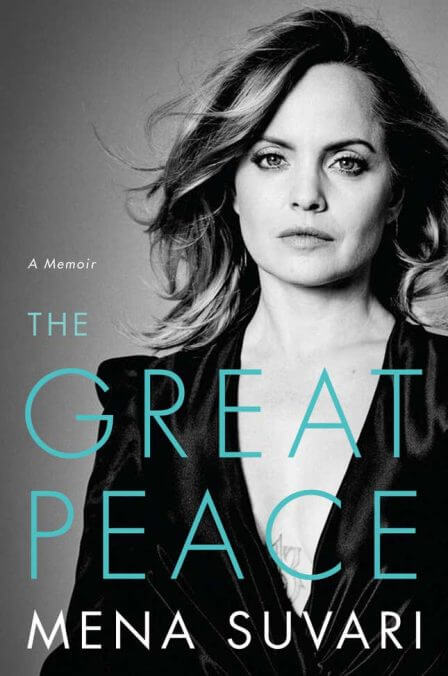

Mena Suvari says she’s never read a celebrity memoir, and does it ever show. Her own memoir, The Great Peace, is an uncommonly graphic chronicle about coming of age in Hollywood and surviving abuse. Suvari writes that she was “inspired by the courageous women who went public with their stories as part of the MeToo movement,” and her story contains several examples of ways men took advantage of her at a young age. Her manager at 16 let her get high in his apartment, “with him fucking me afterward, but yet also saying, ‘Don’t forget to brush your hair,’ and asking, ‘Do you know your lines?’” She met a 26-year-old lighting designer at a rave when she was 17 and stayed with him for three years, during which time, she writes, he demanded anal sex and, eventually, “kinky threesomes at least four times a week.” She describes the relationship as abusive, writing, “Little by little he whittled away the thin layer of self-worth I had left. I thought this was what relationships must be like, full of stress and fighting.”

In the most-quoted passage leading up to The Great Peace’s release, Suvari writes about her now disgraced America Beauty co-star Kevin Spacey, who in preparation for an intimate scene “took me into a small room with a bed and we laid next to each other, me facing toward him while he held me lightly.” In her book, she writes that the scene prep worked: “Lying there with Kevin was strange and eerie but also calm and peaceful, and as for his gentle caresses, I was so used to being open and eager for affection that it felt good to just be touched.” In a conversation with Jezebel, Suvari compared it to an experience she had with a photographer she refers to in her book as Branden, who took her headshots at 15, undressed and kissed her, refrained from sex, but as she writes “had me in every other way that was barely legal and satisfying.” Many of the scenes of her early years in Hollywood involve older men closing in on her. She married her first husband, cinematographer Robert Brinkmann, in 2000 and divorced him in 2005. He’s 17 years older than she is.

The details are harrowing, but the overall effect of her writing is strangely intoxicating. In unfussy prose that sometimes reminded me of a cross between Go Ask Alice and Soleil Moon Frye’s kid 90 documentary, Suvari transports the reader a drug-hazed youth hangout in the ’90s (“I got heavily into Deee-Lite,” she writes of her raver days). Suvari describes copious substance ingestion (including an intense weed habit and a stint with meth), her shame at contracting herpes, and her time on film sets, including those of her most-seen movies, American Pie and American Beauty, both released in 1999. What’s most impressive is Suvari’s willingness to admit to mistakes and even at times risk coming off as unlikable. She wants people to read and relate to her story, but beyond the notion that the truth has set her free, there isn’t a didactic moral takeaway.

“It’s not like I’m offering all the answers in the book,” she told Jezebel by phone on Monday. “I’m offering all of these moments in hopes that we can have conversations around it, because I don’t know, I’m still figuring all of that out.” An edited and condensed transcript of our conversation is below.

JEZEBEL: How do you feel about your book today, the day before it comes out?

MENA SUVARI: It was something that I felt so completely compelled to do as far as telling my story. Initially, I didn’t think that I would write a book. I never saw myself as that kind of person. I doubted myself. I think I looked for what I thought would be a more creative way to tell my story. And then upon sharing some of what I found [in her storage unit in 2018]—my diary and the red binder [of other writings] that I made in the late ’90s, which I had titled The Great Peace—I was encouraged to share it as a memoir and really tell my whole story and then add some of the poems and whatnot from the binder into it.

Are you able to sit back and be proud of your work or are you critical of yourself?

I think I’ll always be critical of myself. I wonder if it’s even possible to not be. I’ve never felt I was good enough. So for sure, that’s always going to be there. I’m proud of myself in the sense that I don’t feel like I’m living in fear anymore. And it feels good to be authentic, to be transparent, because I believe that’s why we’re here: to communicate with one another. To learn and hopefully grow and inspire one another. That just feels good for me to do and that overrides the nerves.

I’m trying to showcase in the book the process of me realizing that I always had a voice. That it’s okay for me to talk about these things because I doubted that the whole time. My whole life. I felt like “Well, you know, I didn’t end up in the hospital over it, so it must not have been that bad.” I just suffered silently. “Well, you know, my skull wasn’t cracked open over it, so I guess I really wasn’t abused. I guess I really didn’t experience trauma.” And that’s not cool. I don’t think that it is that black and white.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-