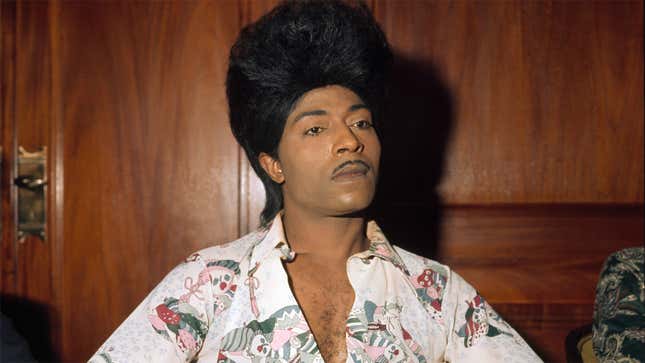

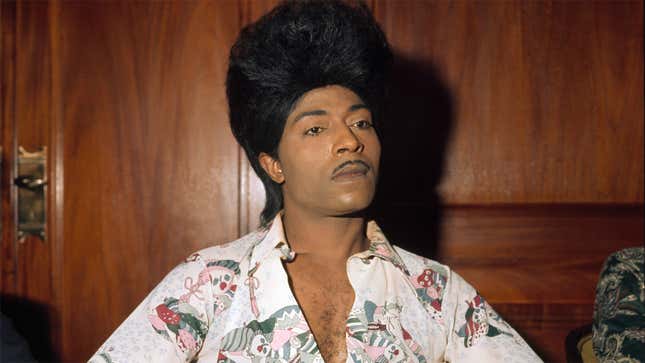

‘Little Richard: I Am Everything’ Saves a Black Queer Icon From ‘Obliteration’

Director Lisa Cortés talked to Jezebel about her effort to "decolonize the rock doc" and emphasize "human connection" with her subject.

EntertainmentMovies

Superficially, Lisa Cortés’ Little Richard: I Am Everything (in theaters and streaming on Friday) might look and feel like a standard rock doc. Indeed, its purview is a cradle-to-grave portrait of its subject, rock pioneer Little Richard, and it’s populated with music (“Tutti Frutti,” “Long Tall Sally”), archival footage, and talking heads pontificating on the greater implications of Little Richard’s cultural contributions. However, I Am Everything has what few rock docs have—an inimitably flamboyant subject, for one thing, who not only had a direct hand in the formation of the genre of rock and roll but also revolutionized the rock star as an icon. The pacing, too, is uncommonly frenetic, as if tailored to mimic one of Richard’s sprightly piano lines, and the academics’ commentary is virtually uniform in its clarity. There’s not a stuffy blowhard in the bunch.

Via Zoom last week, Cortés told Jezebel that one of her intentions was “to decolonize the rock doc.” She elaborated: “My goal was to, yes, tell the story of an icon, but also to have moments of magic and revelation and to break through the norms about how you’re supposed to tell that story.” One of her ways of achieving this was to tightly curate her talking heads.

“Who tells a story is important to me,” said Cortés. “I was very intentional with the scholars that I chose, the ethnomusicologists. They’re a combination of Black and queer scholars who are bringing an intimate connection to their commentary and analysis of Richard. And they’re also at times introducing their own personal thoughts. So it takes them from just being on the academic pedestal that they so brilliantly sit upon—they have a human connection with his story, and I think that broadens the conversation.”

Cortés said she’s been a fan of Little Richard’s since she was a kid, but the impetus to make a documentary about him kicked in upon his 2020 death, when she realized that a fleshed-out story of his life had not yet been told. “There’s more to him than, ‘Shut up,’” said Cortés of the term her subject helped to popularize. “There’s more to him than being a comic foil. There’s somebody who is very rich and deep in their contributions to music and to culture.”-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-