“im coming thru on my way home for xmas. wanna grab a beer?”

It was a welcome text message. I was 23, new in town, and had just moved into a rickety apartment with two roommates and a cat named Theo. Our lopsided home was above a barbecue joint; it smelled perennially like pulled pork. I was a little lonely, a little uncertain. A visit from my not-quite-ex, never-really-was boyfriend would be a nice holiday distraction.

We had that beer. And another. Our feet found each other under the table; our hands sought out the familiar. He stayed over. It was fun and easy and years on, unmemorable. I don’t remember much of what we did, but I do remember that he nibbled my nipples.

A couple days after Christmas I started feeling sick. I drove back to my new apartment in a cold sweat and spent New Year’s in a feverish haze. After four days, my roommate pushed me to go to urgent care.

I sat behind a curtain, the cacophony of coughs ringing in my ears, and explained my symptoms: fever, sweats, feeling leaden all over. “There is one other thing,” I told the nurse practitioner. “I have this weird rash on my boobs.” She gestured for me to unhook my bra. It was freezing, but I complied, and pointed to the zit-like bumps ringing my areolas.

“Huh,” said the nurse practitioner, peering in as I drew back uncomfortably. “I’ve never seen that before.” She referred me to a dermatologist.

Of course, I thought. Of course.

I spent much of my childhood in dermatologists’ offices, doing battle with a severe case of eczema that wouldn’t quit. As I grew up, my skin largely cleared. Dermatological anomalies, I hoped, were relics of childhood. I was wrong.

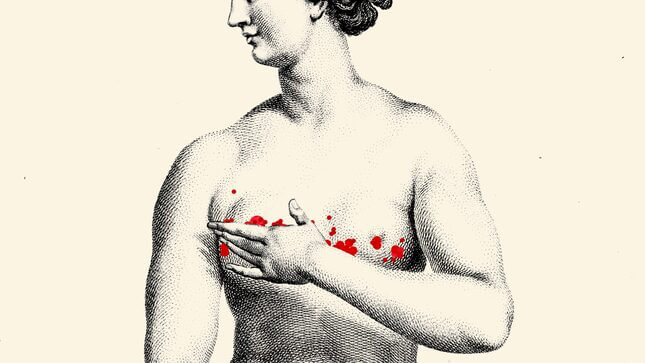

my breasts were their own scarlet letter

Several days later, in the cold white light of another exam room, I tried to feel normal about again whipping out my boobs for inspection by a white-haired dermatologist and his team of associates. The mysterious rash had spread, snaking up my chest and neck, down my torso, onto my face. Some of the volcanic bumps, now a putrid pink-yellow color, had burst and crusted over. The dermatologist leaned in, examined the vesicles, biopsied one my torso, and left with the sample.

He came back to deliver the diagnosis. “Eczema herpeticum,” he said, all too clinically. “The herpes virus has infected your eczema.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I was aghast and flooded with shame. This could not be happening, and it could not be happening to me.

“T-t-t-that’s impossible,” I stammered.

“Were you intimate recently? Do you have a partner?” one of the associates asked carefully.

“No,” I retorted, my face reddening. It was a half-truth that didn’t matter: my breasts were their own scarlet letter.

“We’ve never seen it quite like this,” another associate added. “Do you mind if we take a picture to share at an upcoming conference?”

I nodded dumbly, imagining even more people in white coats looking at blown-up photos of my rash covered body on a fold-out poster board. My breasts might be pocked and crusty, but at least they could contribute to science.

Herpes is extraordinarily common: roughly

67 percent of the global population under the age of 50 has the virus. Eczema is common, too, but

eczema herpeticum is not—it occurs in less than three percent of the eczema patient population and affects approximately one million Americans. It is, however, dangerous: the vesicles can spread to the eye and cause scarring and blindness. Patients can contract meningitis and encephalitis; their internal organs can be compromised. Left untreated, eczema herpeticum can be fatal. Prior to the development of antiviral drugs in the 1970s, patients regularly died.

If only I’d known that deadly cold sores could cover my entire body, and possibly threaten my life, I would have done more to prevent it, including kissing fewer frogs

My childhood eczema had taken a decidedly adult turn: I had unknowingly weathered a dermatological emergency-cum-STD. I left my doctor’s appointment with a hefty dose of antivirals and antibiotics yet nothing to temper my shame. Why had none of the many dermatologists I’d visited ever bothered to tell me eczema herpeticum was a thing? If only I’d known that deadly cold sores could cover my entire body, and possibly threaten my life, I would have done more to prevent it, including kissing fewer frogs.

“We’re are not really trained to talk about [eczema herpeticum],” said Dr. Peter Lio, Clinical Assistant Professor of Dermatology & Pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, who specializes in treating eczema. “We wait until it shows up. There’s such a stigma that I never use the word herpes. I say, ‘This is from a cold sore,’ because if you say herpes, patients are like, ‘Ahhh!’”

But it is herpes. So how can we talk to our doctors, and how can our doctors talk to us, about the weird stuff happening to our bodies in a way that is simultaneously honest, compassionate, and judgment-free?

Dr. Robert Arnold, Director of the Institute for Doctor-Patient Communication at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, says it’s doctors’ responsibility to make sure patients aren’t beating themselves up about their illnesses. “If you’re feeling shame,” Arnold explained, “how can we acknowledge that, and normalize that? Because if you end up with PTSD—or your illness is markedly interfering with your life, I haven’t done a good job of caring for you.”

Lio teaches workshops on patient-centered care in dermatology. “You have this classic image of the doctor as paternalistic that you have to overcome,” he explained, “but good clinicians do that naturally.” Doctors, Lio said, need to ask quality of life questions: “How are you sleeping? How is your work life, school life, family life, sex life? Is your condition really messing with you? How are the treatments working for you?” They also need to be available for regular follow up.

That’s not as easy as it seems since time and money often limit the delivery of compassionate care. Medicine, Lio said, is hamstrung stuck “right in between capitalism and humanism.” Doctors are under pressure to pack in as many appointments as possible during the day so they can bill out to insurance companies, and there’s only so much information you can cover in a 10-minute appointment.

“I’m kind of like a plumber,” Lio added. “If I’m not in the office seeing patients, I’m not making money.”

Often, Arnold said, doctors and patients have mismatched expectations, and patients can have too much faith in medicine. “When things happen that are unexpected or you never could predict, our society seems to suggest that it’s got to be someone’s fault. For many people it’s disappointing—we want to have known,” he explained.

It turns out that my desire to know I was at risk of contracting eczema herpeticum before it happened was wishful thinking.

“It would be nice if we were able to control everything about our health and our body,” Arnold added. “We might get better at prediction, but always knowing is never going to happen. What you’re asking for is reading the future.”

I liked my boobs before all this; I desperately wanted to like them again

In the weeks following my diagnosis, the scabs on my breasts crusted over and fell off. In their place, bumpy scars appeared, accompanied by occasional searing nerve pain deep in my breast. I started taking vitamins and stopped going out. I felt unsettled in my body; betrayed by it.

I liked my breasts before all this; I desperately wanted to like them again. One wintry afternoon, I went to the lingerie store downtown and spent money I didn’t have on bras—the lacy kind with no underwire, the kind that showed off my nipples.

“You can still be sexy,” I whispered to myself in the dim dressing room, fastening the hook-and-eye behind by back. I bought two bras: an oatmeal-colored one with thick straps and a mauve bra with a tiny bow at the sternum. It was a kind of ritual sense-making: I took the confusing things that happened to me and wrapped them up in lace.

Perhaps by shrouding my breasts, I thought, I might be able to reclaim them.