The Abortion Provider Whose Clinic Was Beloved by Her Community

Carol Dunn faced down arson, break-ins, and an anthrax hoax to give women in Toledo a haven in which they could process their anguish and relief.

In Depth

Illustration: Allison Corr

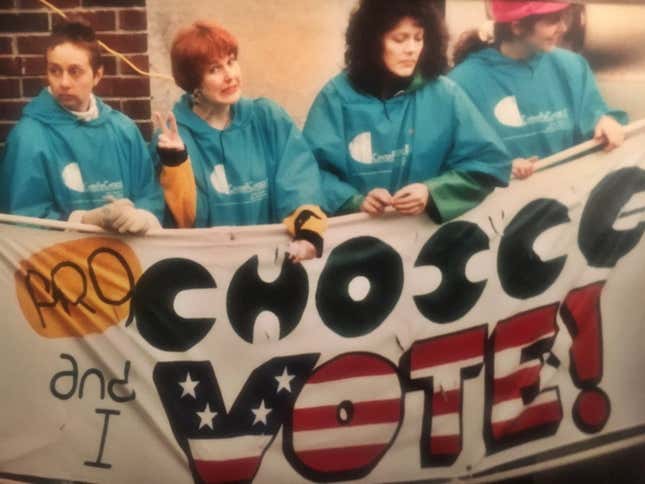

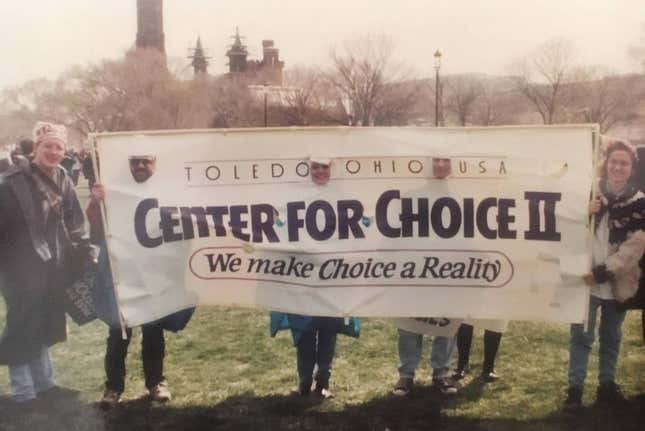

Not so long ago, one of the most formidable abortion providers in the country could be found in the reproductive healthcare desert of Toledo, Ohio. Her name was Carol Dunn, and for three decades, she owned and operated the Center for Choice, one of the city’s only clinics. Like abortion clinics today—the ones that can remain open in an effectively anti-abortion country—it faced waves of violence aimed at it by those who thought they knew better than the people who sought its care.

In 1986, Toledo housewife, anti-abortion activist, and arsonist Marjorie Reed famously set fire to the Center for Choice. The damage forced Carol to relocate. That same year, her new clinic was broken into and the hoses of the machines used for first-trimester vacuum aspiration abortions were cut. In 1989, nearly 60 protesters were arrested after jumping from a truck and blocking the clinic’s doors for more than 10 hours. Two years later, a man jammed the office’s answering machine by repeatedly calling and reciting Bible verses. There was even an anthrax hoax in 1998. As Carol described to me during an interview in 2016, an employee at the clinic opened an envelope postmarked from Cincinnati to find a suspicious powder substance inside. The building was evacuated, and Carol and the employee were treated as though they had been infected with a deadly bacterium.

Later, Carol would recall zipping up the Hazmat suit officials from the health department had given her and thinking, in the midst of the uproar: “This son of a bitch better fit.”

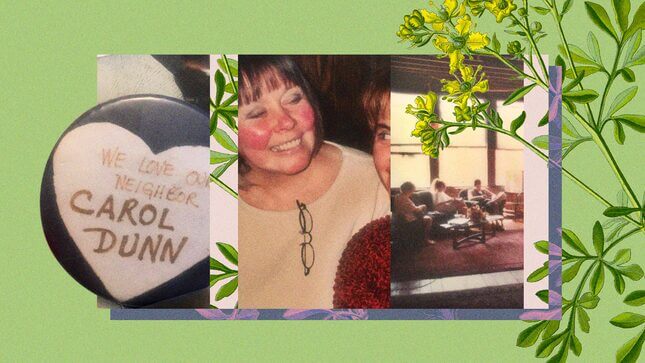

When the attacks on the Center for Choice were no longer enough for anti-abortion protestors, they began picketing Carol’s home and community in Toledo’s Old West End, a 25-city-block stretch of Victorian and Edwardian homes. She told me of a year in which swaths showed up to her neighborhood’s annual summer festival, armed with posters of fetuses and distributing fliers that warned there was a “murderer” living in the Old West End. In response, Carol’s neighbors made buttons emblazoned with “We Love Our Neighbor Carol Dunn” to wear on their chests.

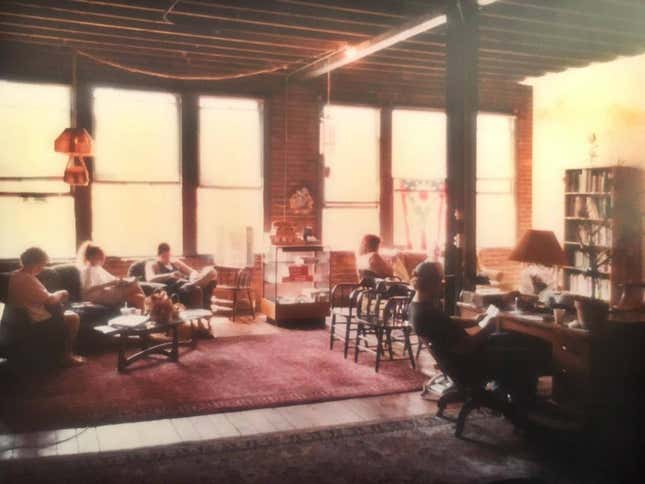

Carol wanted to be “the Merle Norman of abortion clinics.” The privately owned, women-founded and led makeup franchise—credited for pioneering the “try before you buy” philosophy—was a model for her as she sought to create medical spaces that didn’t feel sterile, and instead, maintained an air of sophistication patients could take comfort in. The Center for Choice opened its doors in 1983 on the second floor of a building in the downtown warehouse district, looking more the part of a loft belonging to a New York nepotism baby than an abortion clinic in Ohio. Its waiting room featured exposed brick walls, overstuffed chaise lounges, floor-to-ceiling windows from which natural light streamed, and evocative artwork awash in muted tones on every wall.

One of the canvases, captured in a photograph of the waiting room, appeared to depict the entangled limbs of a couple’s embrace. Years later, I asked Carol if my interpretation was correct. “No, honey. That’s a woman bent over in anguish,” she said. She felt it was appropriate for a place in which her patients might experience a complex collection of emotions, from torment to relief. “I wanted to make something ugly and painful and traumatic as pleasant for women as possible,” Carol told me.

Oftentimes, pro-abortion discourse centers a person’s trauma in an attempt to legitimize an option that’s already inherently justifiable. Rape, incest, and the like are listed as if they’re non-negotiables for a procedure to be performed in a colorless facility, devoid of warmth and offering only the distraction of an out-of-date People magazine and a smattering of water-stained pamphlets. The Center for Choice was no such place, because Carol treated abortion with aplomb, as if it were every bit the experience one wanted. In her mind, it was not a last resort, but a dignified decision. A more trained eye would see past the impeccable aesthetics to understand that the wicker chairs, plush carpeting, and art were a covert extension of Carol’s brand of radical activism, and her commitment to cultivating joy—even if it didn’t make sense, and especially when the circumstances didn’t feel very joyful at all.

Her reason for doing so was simple: She didn’t want anyone to suffer the circumstances she had. In 1964, when she was in her early twenties, Carol underwent a botched abortion. She’d been given potassium permanganate—an oxidizing agent, a tissue-destroying chemical, and in significant quantities, a poison—by a man who was not a doctor in a Toledo apartment. Hours later, she drove herself to the hospital, bleeding profusely. Because she wouldn’t reveal the name of her abortionist, doctors threatened to refuse treatment. Ultimately, she was admitted for an extended stay. Six years later, after abortion became legal in New York, Carol became a referral agent for Planned Parenthood, directing community members in need of the procedure to a nonstop flight from Toledo to New York’s LaGuardia airport. She remembered that airline staff called it “the abortion flight.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-