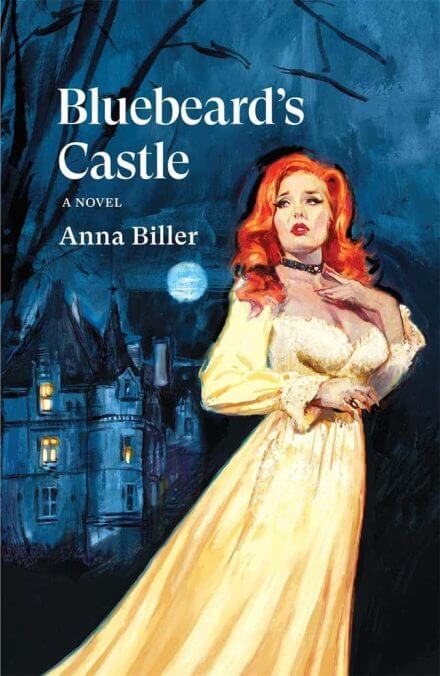

Romance Novels Have a Pesky Habit of Romanticizing Abuse. Not ‘Bluebeard’s Castle’

Filmmaker Anna Biller’s first book, a gothic romance-turned-horror, takes the “I can fix him” meme and flips it on its head.

BooksEntertainment

“Anger for a man is like tears for a woman,” a doctor tells Judith Moore, the doomed heroine of filmmaker Anna Biller’s new novel, Bluebeard’s Castle (out this week). “We have to let it out sometimes.” The male doctor is making a house call as Judith wrangles with PTSD and anxiety after her husband, the endlessly charming, endlessly seductive Gavin Garnet, physically attacks her amid an argument one afternoon. Judith doesn’t recount the attack to the doctor but alludes to her fears of her husband’s anger issues; she’s essentially told Gavin’s rage is just another case of boys being boys.

Bluebeard’s Castle begins as a classic love story that flows like a rose-tinted montage cut from an Old Hollywood film. Gavin introduces himself to Judith as a baron estranged from his family, then thoroughly seduces the romance novelist with the aggressive love-bombing and very sort of romancing that she depicts in her books. They marry within days of meeting each other, live in an enchanting gothic castle that Gavin purchases with Judith’s money, and embark on their fairytale happily ever after. But then, things get predictably complicated. Holes in Gavin’s story begin to form like cracks splintering off from a central fissure, and Judith comes to realize she’s living a modern version of the classic Bluebeard folktale about a man who kills all his wives with impunity.

Yet, through every lie Judith catches her Bluebeard in, and through every threat he makes to her safety, she can’t bear to leave him. Each of his psychic and physical attacks on her, Judith reasons (and is told as much by Gavin), is an extension of his own victimhood, and her failure to sufficiently love and consequently heal him. “The woman craves the love that is starting to disappear, and she forgives the abuse because the man convinces her that he’s the one who is hurting,” a passage from a book on domestic violence cautions Judith at one point in the novel.

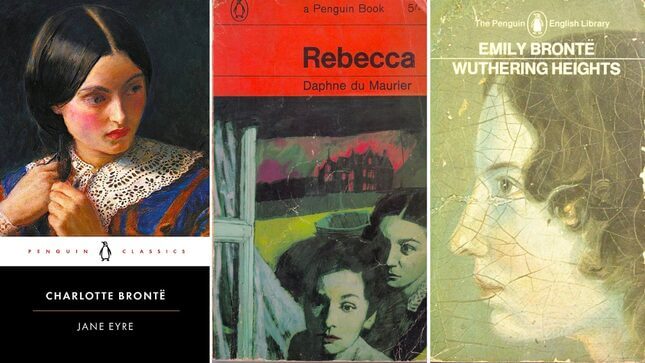

Biller’s prose reflects that of a 20th century gothic classic, extensively referencing and drawing clear inspiration from the likes of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, and Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. Our only reminders of the novel’s modern setting are occasional references to iPhones and social media sleuthing. Biller, director of Love Witch (2016) and Viva (2007), told Jezebel that with Bluebeard’s Castle, she saw an opportunity to subvert the trope of the dark, brooding male love interest who must be tamed and civilized by the unconditional love of his heroine, regardless of who he’s killed or locked away in a closet. Gavin is a composite of Jane Eyre’s Rochester, the mysterious love interest who keeps his first wife in the attic; Wuthering Heights’ Heathcliff, the obsessive lover driven by maddening passion; and Rebecca’s Maxim de Winter, dapper and charismatic and ultimately violent toward women.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-