An Hour Renting Emily Dickinson's Bedroom Where She Wrote Her Entire Life's Work

In Depth

“Sweet hours have perished here;

This is a mighty room”

You can visit the café in Edinburgh where J.K. Rowling supposedly sat penning Harry Potter, tour Ernest Hemingway’s house in Key West, still crawling with cats, or see William Faulkner’s Rowan Oak, a Mississippi home flanked by cedar trees. But few writers have written their entire life’s work—nearly 1,800 poems, in Emily Dickinson’s case—in just one room.

For one hundred dollars an hour, you can rent the second-floor bedroom in Amherst, Massachusetts where Dickinson spent a huge portion of her life. The Dickinson Homestead on Main Street was purchased by the Parke family in 1916, and sold to the Trustees of Amherst College in 1965 (it quickly became open for public tours). After twentieth-century wallpaper and floorboards from Dickinson’s room were removed, clues to the original floor coverings and interior design during the Dickinsons’ occupancy were discovered.

In 2003, Amherst College acquired “The Evergreens,” a dwelling directly next-door to Emily’s house, once inhabited by her brother Austin. The buildings were merged to create the Emily Dickinson Museum. In further attempts at historical accuracy, the two-year restoration of Dickinson’s specific room was completed in 2015. Although the Museum has been visited by thousands every year—eager to peer inside the eminent poet’s room on the guided tour—this is the first time her chamber has actually been rentable.

As a girl, Dickinson was sociable and gay. She attended school, played piano, and did normal kid things, giving no hints of impending misanthropy. By her thirties, she was serious about writing. She began living in increasing seclusion from society, though maintaining lengthy letter correspondences with friends and close relationships with her family (who also lived on the property—so she was technically never alone). By the time she reached forty, Dickinson hid from houseguests she had previously received, and attended to the outside world only in her garden and her verse.

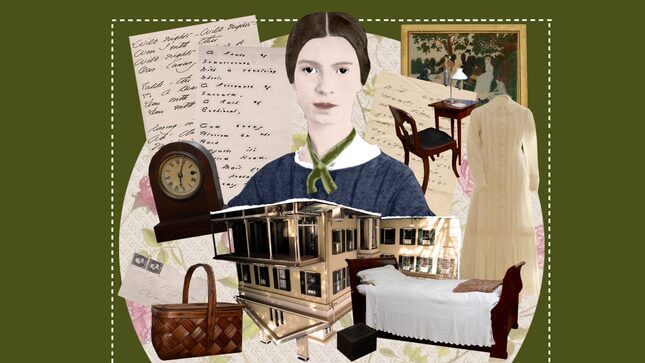

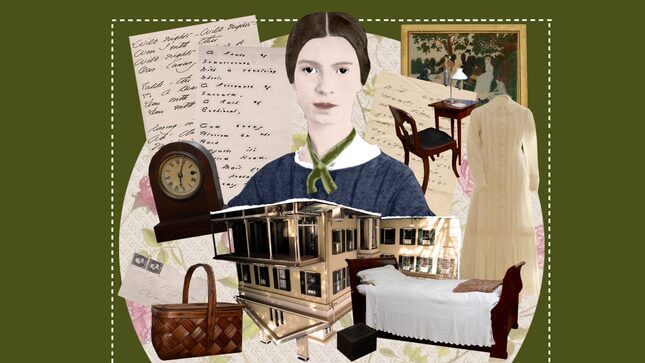

It’s from her bedroom that Dickinson composed everything. “Dickinson’s genius always kept a fixed address,” Dan Chiasson wrote in a December 2016 issue of the New Yorker. “She was a scholar of passing time, and the big house on Main Street was the best place to study it.” The room has pink-flowered wallpaper (based on 19th-century wallpaper fragments found during the restoration), lace curtains, a small single bed, a chamber pot, a writing desk with ink and convincingly scribbled-upon paper, six tattered books, a stove, a face-washing basin, a picnic basket, a rocking chair, and a clock forevermore reading 6:05—a time that could indicate dawn, when the birds rise, or the golden-soaked dusk of summer. There is a headless mannequin at the center of the room, cloaked in a white dress, as popular legend stipulates Dickinson only wore white. (This theory hasn’t been proven; though her one surviving dress is white, and friends and townsfolk have described her garbed in the color, she makes no reference to such a preference in her work). The dress is a facsimile, and the original is kept at the local historical society.

If you “rent” her sun-flooded corner room now, you can bring along a laptop or pencil and paper, and stay for up to two hours—though you can’t close the door behind you, as the cherished hope of many a pervert is probably to drop trou inside. The bed and stove alone are items originally kept by Dickinson in the mid-1800’s, though there are exact reproductions of the other furniture, like a writing table and bureau, and everything is arranged so as to imitate her tenure. The genuine writing stand and bureau both reside at Harvard (those bastards get everything); the desk is tiny, barely 18 inches across, and probably more appropriate for a nightstand than for scribbling rhyme. The bureau is one of the places where hundreds of Dickinson’s poems were found stashed after her death. The room’s authenticity is only marred by two brazenly modern lamps and a folding table where guests are meant to sit and feel inspired. You can’t touch anything— and there is a small, polite rope barring you from approaching the bed.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-