Adrienne Shelly’s Husband Will Not Let You Forget About Her

The Waitress actress/writer/director, who was murdered in 2006, is the subject of a new HBO documentary directed by Andy Ostroy.

EntertainmentMovies

“I was living the worst nightmare imaginable,” says Andy Ostroy in the documentary he directed, Adrienne. He’s referring to the senseless murder of his wife Adrienne Shelly in 2006. By then, Shelly had established herself as an indie staple, a well-respected actor who was on the verge of a career breakthrough as an auteur. If you’re having a hard time placing her name or haven’t heard of her at all, you aren’t alone. Part of Ostroy’s objective in Adrienne is to pay proper public tribute to an overlooked life and career.

Shelly initially made a name for herself after performing in well-regarded movies during the indie boom of the late ‘80s/early ‘90s (including her debut, Hal Hartley’s 1989 film The Unbelievable Truth, and Hartley’s 1990 follow-up Trust). When she was killed, she had wrapped the movie that she would come to be best known for: Waitress, a vivid and compassionate comedy released posthumously in 2007, which was ultimately adapted into a long-running Broadway musical. Shelly wrote, directed, and starred in the movie.

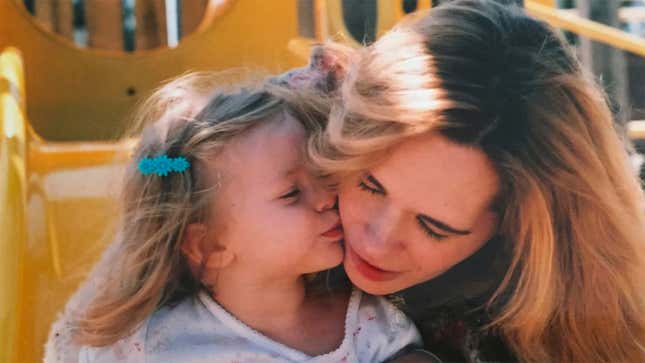

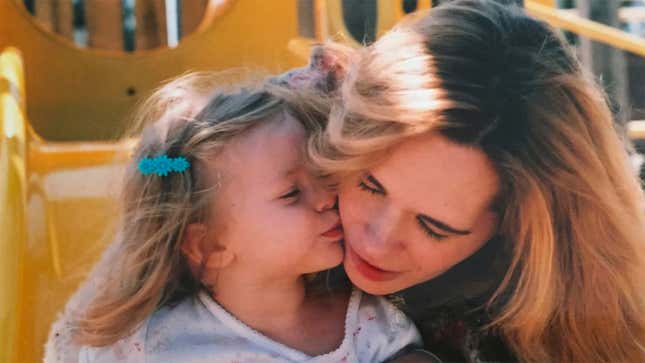

There’s an early scene in Adrienne, which is now streaming on HBO, in which Ostroy polls people outside the Brooks Atkinson Theatre, where Waitress ran from 2016 to 2020. Despite Shelly’s name being on the marquee, it’s clear that the audience largely doesn’t know who she is. Ostroy’s doc, then, serves as a reminder of a life that was cut short. It features several of Shelly’s friends, family members, and colleagues, and tons of archival footage (culled from “hours and hours and hours” of tapes Shelly had left behind). It is not a true-crime doc, per se, but it does rather methodically take viewers through November 1, 2006, when Shelly was found hanging in the shower of her apartment. The police initially ruled her death suicide, but because Ostroy pressed (why would someone so happy, with a 2-year-old child, who had just produced the creative achievement of her career, kill herself?), the cops reexamined and eventually found a footprint in her bathtub belonging to Diego Pillco, who had been working in the building. Pillco eventually confessed to the crime and was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Ostroy eventually met with Pillco on camera to get the full story of his wife’s murder. That’s in the doc, as is footage of Ostroy discussing Shelly’s life and death with their daughter Sophie, who is now 17. Adrienne is imbued with life and loss—it gives and takes, like life itself. For years, Ostroy has been publicly devoted to preserving Shelly’s legacy, having established the Adrienne Shelly Foundation for women filmmakers (it counts Chloe Zhao, who won the Best Director Academy Award this year for Nomadland, among its grant recipients). Adrienne is just the latest step in this endeavor. In a recent interview with Jezebel, Ostroy discussed the making of his movie, meeting with his wife’s murderer, and why he doesn’t believe in the concept of closure. An edited and condensed transcript of our conversation is below.

JEZEBEL: How long had this documentary idea been bubbling?

ANDY OSTROY: It goes back somewhere around three and a half, four years. The real trigger was when I took Adrienne’s mother to see the musical Waitress on Broadway. Before the curtain went up, she got to talking with a few women sitting behind us and eventually shared that Adrienne had something to do with this musical. And they were like, “Oh, that’s great. Is she here tonight?” That got me thinking, as I looked around the theater at well over a thousand people, how many of these people know who Adrienne is and the story of her life and her death. That’s when I decided, because Adrienne was a filmmaker and a storyteller, that if I’m going to tell this story, it seemed most fitting to honor her and pay tribute to her through film.

Early in the movie, you interview people outside the theater where Waitress is playing, and person after person doesn’t know who Adrienne is. It seems like preserving her legacy was key to you.

The film always had three components: life, death, and aftermath. In terms of what questions that I seek to answer through this film, the three main ones were: Who was Adrienne Shelly? What really happened the day she died? And how does her family navigate the unthinkable? So bringing her back to life for viewers, having them get to know her, fall in love with her, and then grieve her loss in a profound way and perhaps be inspired and motivated to go back into her catalog and check out her work they may not have seen before, that was the real motivator for me.

You framed Adrienne as the motivator here, and not your own experience. Has this process been cathartic for you? At the end of the movie you say, “I struggle with the concept of closure. My life will always be about grief.” Did this process bring you any closer to closure or is Adrienne’s death a perpetual void that you live with?

I don’t believe in closure. I’m glad that it works for other people to feel that they’ve achieved that place. There are theories and books, you know, the five stages of grief…I personally don’t understand the concept of getting to stage five, getting through it, and then feeling like, “OK, I’m done. That’s it! No more pain, no more grief, no more sadness.” That didn’t work for me, and it still doesn’t work for me. The film isn’t necessarily cathartic in the way most people would think. It didn’t provide healing, but it provides a great sense of satisfaction and gratification, knowing that the mission I set out to achieve is the mission I believe I did achieve, which is to humanize her, to show her as a wife, as a mother, as a daughter, sister, friend, colleague, and not just a murder victim.

What was the process of revising the past through all the archival footage like?

During the editing process for a little over a year, I watched, every day, tons of footage of Adrienne, of me and Adrienne, of me and Adrienne and our daughter, of Adrienne and our daughter, and with friends and family. It just was like reliving that life again. That was painful and emotionally challenging at times. But, I kind of equate it to people who climb Mount Everest. I mean, for me, making this film was like my Mount Everest climb. You kind of know what it’s going to be like going in. You know it’s probably going to be horrible. But then you know when you get to that summit, it’s going to be amazing and all worth it. I would do it all over again because the sausage-making was never my concern. It was the sausage. The sausage is exactly what I set out to make. The film is 100 percent what I envisioned it being in my head.

Was there any joy in getting to spend so much time with Adrienne again in filmed form?

It’s very bittersweet. I’d be like, “Oh my God. She’s so funny and amazing and cute. Oh, we had such a great time together…Oh shit, she’s dead.” It would just be like up, down, up, down. It was just it was an emotional rollercoaster. The painful reality of that was inescapable.

Did you absorb filmmaking knowledge from Adrienne?

When you’re with someone, sometimes you just don’t talk about stuff that you wish you did after they’re gone. Filmmaking was what she did. We had a life together. We were a married couple. We had a child. That’s the stuff we enjoyed together and talked about. What I did learn from her that helped me, you see her say in the film: “You have to stick to your guns. You have to not be afraid to ask for what it is you need.”

Throughout the process, I won’t say that Adrienne talked to me, but I did use the essence of her in my head to guide me: “What would Adrienne do?” So she was with me throughout. On the ride to the prison, I remember saying to myself, “This is the one time she’s not with me.” She would be like, “I have no idea what to tell you here. This is out of my wheelhouse.”

I’d be like, “Oh my God. She’s so funny and amazing and cute. Oh, we had such a great time together…Oh shit, she’s dead.”

Looking back on it, are you happy with the way the conversation went with Diego Pillco?

I had two goals for that encounter. One was to find out what happened that day because he had lied at his confession. He had lied at his sentencing, and I felt unresolved and unsettled. I knew always that I would someday reach out to him, and I wasn’t ready to do it until around 10 years after Adrienne died. I needed to be in a certain headspace. And that was also when I started to conceptualize the film. So it was just like, okay, it’s going to be part of the film. And [the second goal was] to humanize her for him. I assume that in his head, he had an image of her, which was very limited, very brief, of a woman who was panicked and calling out for the police. I wanted him to see a wife, a mother, a daughter, a sister, a friend, a colleague. I wanted him to see that image, to see that life for the rest of his life. And truthfully, I wanted to haunt him for the rest of his life. I want him to know the life he took. So with those two goals in mind, I know that I accomplished that, and I think that is clear in the film.

In court, you told him, “I will spend the rest of my days hating you with every fiber of my being for what you have done.” Did that turn out to be true? Do you still carry that hatred around?

Everything is not mutually exclusive, right? I’ve always heard that you need to forgive so that you can move on. If anyone looks at my life for the last 15 years, no one can say, “This guy is stuck.” I’ve spun gold from Adrienne’s death in ways that have turned her death into something positive. I have been able to channel what I need to do positively in this world and for myself and for my family. At the same time, I have no problem saying that my feelings are still the same. I lost the love of my life. I lost my daughter’s mother. My daughter lost a mother. And so while I don’t walk around the street kicking garbage cans, which is, I think, what people sort of envision when they think someone’s still angry, I don’t understand how those feelings could ever go away. What this guy did was horrible. It almost destroyed a family, and it just is what it is, you know?

I wanted to haunt him for the rest of his life,

Toward the end of the film, Paul Rudd—Shelly’s friend and a founding board member of the Adrienne Shelly Foundation—delivers an interpretation of Adrienne’s impact that contrasts with your stated goal of getting her name out there. He says, essentially, that for the people who attend Waitress on Broadway who don’t know Adrienne, her work stands on her own and that’s the best thing an artist can hope for. Was that a revelation for you?

That was a big turn for me because clearly, I go into it saying, “What the hell? Nobody knows Adrienne.” And then sitting with him, I realized from an artist’s perspective the importance of work standing on its own, as he says, that that’s really the greatest thing you can achieve as an artist. When I sort of separate my own personal attachment to the story and just look at things holistically, it’s like, that musical was a success for four years. I mean, wow, that’s incredible. She created that. Without her, that Broadway marquee doesn’t exist. For me, I would say that [interview] was probably the only real transcendent moment for me in the film, where I changed the way I viewed some things very deeply.