A Testament to the Horrors of Slavery & the Perseverance of Black Women, Rendered in Needle and Thread

How a hand-embroidered seed sack tells the intergenerational story of Black women surviving in America

BooksEntertainment

Image: Courtesy Middleton Place Foundation

As a young woman with modest means and few prospects, Ruth Middleton transformed her life by moving north. Taking a leap into the unknown as a Black woman in the 1910s required tremendous courage. Ruth was still a teenager at the time, living in Columbia, South Carolina, and laboring as a domestic. She may have already met her future fiancé, Arthur Middleton, a South Carolinian from Camden and a tiremaker by trade. And she would have known from what she heard and saw, and perhaps from incidents in her own life, that the South was still a dangerous place for African Americans at the start of the new century. The first generations to be born to freedom found few job opportunities beyond the agricultural work their forebears had done, risked indebtedness in the sharecropping system, and faced public humiliation as well as unpredictable violence in everyday life. Perhaps Ruth and Arthur evaluated their situation and determined that only drastic change would better it. For they, like so many other African Americans fed up with the dusty prejudice of the South, packed their retinue of things and traveled northward seeking safety and opportunity.

Ruth and Arthur made this move amid the uncertainty of World War I and a deadly flu epidemic, joining what historians have called the first wave of the Great Migration, which would, by the 1970s, reshape the demography and political landscape of the entire United States. African Americans, who had predominantly lived in the rural South, relocated in the hundreds of thousands to the urban South, urban Midwest, urban West, and urban North in search of physical security and economic opportunity. Half a million of these travelers relocated to northern cities in the period when Ruth uprooted herself, between 1914 and 1920. They pulled up stakes, packed their bags, and left behind all they knew and many whom they loved. Those who departed must have faced tough decisions about which items they could afford to bring along on the journey and which things they would give away or abandon. Practical objects like skillets and skirts, cherished things like handmade quilts, and valuable items like tools and books might each have been scrutinized, weighed, and considered. We have no inventory of a great migration of things that accompanied African Americans northward and westward. Ruth Middleton’s case stands as a precious exception.

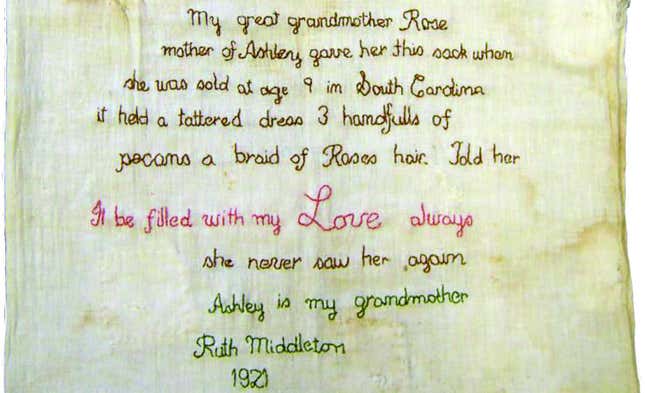

When Ruth arrived in Philadelphia around the year 1918, she brought along a plain cotton sack that her great-grandmother, Rose, had packed for her grandmother, Ashley, when Ashley was a child and the two were ripped apart by sale during slavery. Ruth’s attachment to the textile reflects an important aspect of women’s historical experience with things. While free men have historically owned and passed down “real” property (especially in the form of land), women have typically had only “movable” property (like furniture and linens—and, if the women in question were slaveholders, people) at their disposal. Although American women possessed a limited form of property, they used that property intentionally to “assert identities, build alliances, and weave family bonds torn by marriage, death, or migration.” A New England–born white woman in the colonial era, for example, cherished a passed-down painted chest not only for its function but also for the ways in which the object connected her to her women forebears, reinforcing a sense of belonging not to male ancestors but to a line of women. Ruth Middleton, who would take her husband’s name upon marriage, as was the American legal custom, also took her foremother’s sack as she traveled north. And one day, when she was herself on the verge of motherhood, Ruth decided to annotate it.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-