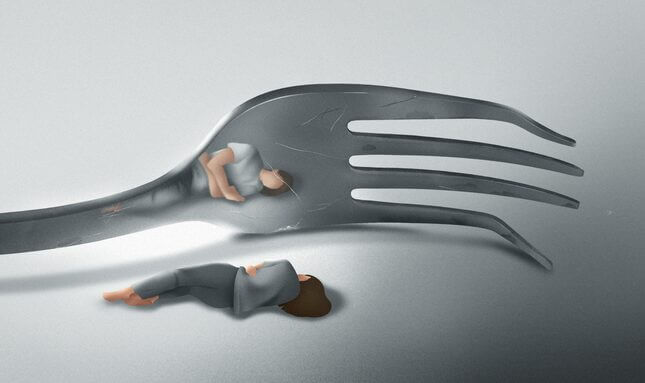

The Stifling Shame I Feel As an Adult With an Eating Disorder

For years, I talked about mine in the past tense, as if it was a resolved issue and not a current danger to my health.

In Depth

Illustration: Anna Kim

“I have problems with food,” I told a new romantic partner.

“Like, you’re bad at cooking?” he asked. This was offensive, since I had already cooked for him on multiple occasions.

We’d been seeing each other for about four months, and I was ready to open up. I had an issue, one that had festered in silence in past relationships. For about 15 years, I’ve dealt with an eating disorder of variable severity. The parts of it that feel most disruptive—purging, diet pill abuse, day-long fasts—are in the rearview, I hope. I’m high-functioning, physically healthy, and able to eat meals socially. And still, I’m undeniably controlled by food and exercise. While it’s easier to pretend I’m fully recovered, doing so also feels tantamount to accepting that my current relationship with food is as good as it will ever get, and I don’t want that for myself. I had sought out a new therapist who said communicating openly with those close to me would help me stop pretending. But I really, really, really didn’t want to.

It’s my instinct to talk about my eating disorder in the past tense, or to not talk about it at all. I do not believe I’m alone: 9 percent of Americans will struggle with an eating disorder in their lifetime. By contrast, 18 percent of Americans will struggle with an anxiety disorder in any given year, and sure enough, in the past month, I’ve spoken with 11 friends who referenced an anxiety problem. Zero mentioned an eating disorder. This is anecdotal, of course—hopefully none of them have an eating disorder—but it aligns with my own experience. I, too, have an anxiety disorder, and I find it far easier to discuss than my food issues.

I am correct, to an extent, in worrying about disclosure. Sometimes, this kind of discussion ignores sensitivity. We saw this play out on a massive scale when Taylor Swift was criticized for a scene in her “Anti-Hero” music video, in which she stepped on a scale that read “fat.” It was meant to portray her experience with an eating disorder, but she eventually removed the imagery from the video because it was seen as fatphobic, which prompted its own backlash from those who felt like she had accurately represented their experiences with eating disorders.

But fear of a backlash is not an excuse for silence, especially not when I’ve been so inspired by other adults who opened up. I can admit that I was moved to tears by an episode of Glennon Doyle’s podcast in which she admitted to relapsing on her bulimia. It felt both groundbreaking and deeply comforting to hear another adult talk about an eating disorder in the present tense, so much so that after listening to the episode, I booked an appointment with my new therapist. It was the first time in a long time I didn’t feel that I “should” be over my eating disorder. From there, I began to unpack why I’m so hesitant to talk about it. The main reason became obvious: shame.

“Misconceptions about eating disorders abound. Three popular ones include that eating disorders are about shallow vanity, affect only young adults and teens, and happen primarily to white females,” Alli Spotts-De Lazzer, licensed therapist and author of MeaningFULL, told me via email. Even though I know the prevalence of eating disorders peaks not in the teens but in the mid twenties for women and early thirties for men, much of my shame springs from feeling like I’m too old to still have one. And not just the age itself—it’s the sense that I failed to recover when it seems like everyone else did. I’ve begun asking people how they recovered. Some say therapy, others say time, and still others say they’re not quite sure when it stopped controlling their lives. (For the record, I’ve had quite a lot of therapy and time.) One woman told me she was hospitalized for an eating disorder as a teenager. I asked her if she still struggled with food, and her response was, “No, of course not—I’m getting married,” as if an eating disorder was a problem that needed to be solved before the rest of her life could go on. Her serious romantic relationship indicated a resolution to a problem I’ve found chronic. And so, I feel left behind, embarrassed, like I haven’t grown up.

Those misconceptions cut both ways. While I’m ashamed to have an eating disorder when it doesn’t feel like a problem meant for me, a person in her thirties, it also feels like a problem exactly meant for me, a privileged white woman. Someone once told me she tried to be empathetic about eating disorders but couldn’t understand them, because in her family, people were just so grateful to have enough food. I felt a lump rise in my throat as she spoke; I too wanted gratitude for having enough food. Instead, when my eating disorder first cropped up in my mid-teens, I got an expensive therapist. And yet, I still had an eating disorder.

telling myself ‘it could be worse’ leads me to forget that there’s help available for me; that there’s a life out there for me in which fewer than 90 percent of my thoughts are about food.

I find my eating disorder especially tricky to talk about because it draws attention to my appearance. As a teenager, I wanted it to create concern—it was a cry for help. At 16, I didn’t yet know that most of womanhood is just resigning your body to constant examination. Now, I’ve been perceived enough. I have no interest in opening up about something that might cause others to scrutinize my body, in search of a heuristic for how successfully I’m combating my problem. Not only does it make me self-conscious, but also, it’s inaccurate. My disorder is more about control than the way my body looks, and its severity has not corresponded to fluctuations in my weight. Instead, I cling to it when the rest of my life is in disarray. The worst relapse I had in the last five years was at the start of the pandemic, when I had no control over the world’s reopening. This is not unique to me. Weight is not an accurate measure of whether someone is still struggling; eating disorder patients can have any body type, and fewer than 6 percent of patients are underweight.

And such attention can turn ugly. “If a person in a smaller body talks about their eating disorder, they might get ignorant comments inferring that they’re choosing to starve themselves and they should just go eat a burger—as if it weren’t a deadly mental illness and it was as simple as eating a burger. Someone in a larger body is often met with flat-out disbelief and encouragement to continue harmful ED behaviors,” said licensed social worker Shira Rosenbluth. Similarly harmful are comments like, “But you don’t look like you have an eating disorder” or, “But I saw you eat that one time,” she continued. This sentiment can come from a well-intentioned place; I’ve heard people express relief that a friend with an eating disorder seemed to “look” better. Still, the very idea of such scrutiny makes me so self-conscious I’m loath to speak about my eating disorder in the present tense when I speak about it at all.

I don’t want people scrutinizing my body, and I don’t want them scrutinizing their own. I can count on one hand the number of friends who have never expressed dissatisfaction or insecurity about their own bodies, and I feel guilty bringing up the subject at all, considering our culture’s obsession with weight. “Even if it’s well-intended, sharing details can provide a how-to manual for vulnerable people,” said Spotts-De Lazzer. “And for people in the throes of an eating disorder, those kinds of details may trigger them to compete. For example, it could be something like this: If he/she/they didn’t eat for X-number of hours, I’ll try for two more than that.”

Because society glamorizes thinness, and because eating disorders are incorrectly associated with weight, they are socially contagious. #EDTwitter is an online community that I assumed was for those with eating disorders to support one another. As I scrolled through, I saw some posts expressing love and asking for help. But I also saw that many, if not most, offered tips on how to develop eating disorders. In my horror, I felt like a hypocrite. I wanted to believe people should be able to talk openly about their eating disorders in the present tense, and here, finally, was a community of people doing just that. Their pro-ED posts weren’t entirely unfamiliar—I’d fallen into similar communities on MySpace as a teenager—but I was looking at them with new eyes. New, healthier eyes, it seemed. So much so that I began to think maybe I didn’t have an eating disorder. I certainly wasn’t struggling the way the most active posters in this community were. Maybe, I thought, maybe I’m just a person concerned with her weight, as so many of us are. And herein lay the great risk of not opening up about eating disorders.

I am lucky to have my physical health, but telling myself “it could be worse” leads me to forget that there’s help available for me; that there’s a life out there for me in which fewer than 90 percent of my thoughts are about food. Doyle addressed something similar in her podcast when she said she doesn’t hide her disorder from her children. She described how when she exhibits behaviors like taking a bite of a cookie and throwing the rest away (something I’ve done myself many times), she makes sure her kids know this is disordered, not healthy. Instead of normalizing it, she calls it what it is.

it’s not until we start to talk about them—not as resolved issues of the past, but as very real, present dangers—that we can disband these assumptions.

“It is hard for people to recognize that they have an eating disorder when there is such widespread acceptance for things like intermittent fasting, cutting out entire food groups, and compulsively exercising,” said Dr. Charlotte Markey, a professor of psychology at Rutgers. In a scene in Center Stage, ballet dancer Maureen is trying to tell her mother she wants to quit dancing, and one of her reasons is it’s making her sick. She confesses to throwing up everything she eats, and her mother responds, “You watch your weight, there’s nothing wrong with that.” Of course, there is something wrong with it.

It can take three years for an eating disorder patient to seek help—and failing to talk about it will only extend this timeline. “Eating disorders thrive in isolation and secrecy. Sometimes talking about it more openly can be healing. It can also help challenge false stereotypes about eating disorders,” said Rosenbluth. People of color have similar rates of eating disorders to white people but are less likely to seek treatment. Additionally, according to some estimates, one in three people with an eating disorder is male, though men rarely speak openly about them and face stigma when they do.

There are ways we can begin to open up. “As with any important and vulnerable conversations, it’s usually best to make sure that both parties are available to each other. First, state your intentions, such as, ‘I want to share something important to me with you.’ Then, make sure they can be present and available: ‘Is this a good time?’ or, ‘When would be a good time to connect?’” Spotts-De Lazzer said. “Some people will feel safer than others to share with. Pick thoughtfully. Sort through what you’re initially willing to talk about and with whom. Start there. Also, consider scripting out what you want to say so you have an anchor and can even read it, if needed.” She adds that for anyone who feels they can’t share with their own community first, an eating disorder support group or specialist could fill in. I’ve found online support groups myself that helped. Initially, I kept my video off and my camera muted. I liked that I was able to choose my level of engagement, and not share anything (even my name) until I was ready.

Before I started working with my new therapist, and before I started writing this essay, I would have said the reason I didn’t want to communicate about my eating disorder is other people’s misconceptions about them. I would have said that I personally know all the statistics—I’ve Googled them compulsively, I can tell you that eating disorders affect all kinds of people. I would have said I know eating disorders are serious problems, and I know they’re about much more than privilege and vanity. I would have said the problem is that other people don’t know as much as me, so I can’t open up to other people. But I was ignoring my own misconceptions. I’m wrong to believe I should be embarrassed. I’m wrong to assume my friends don’t want to know. Mostly, I’m wrong to think I’m the only one suffering. And it’s not until we start to talk about them—not as resolved issues of the past, but as very real, present dangers—that we can disband these assumptions.

So I told my new partner. “My sister had an eating disorder,” he responded. “They’re horrible. How can I help?”

If you or someone you know needs help, contact the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) online or at (800) 931-2237. If you have an emergency, text NEDA at 741741.

Ginny Hogan is a stand up comedian and writer. She’s the author of “I’m More Dateable than a Plate of Refried Beans,” and you can find her on Twitter at ginnyhogan_.