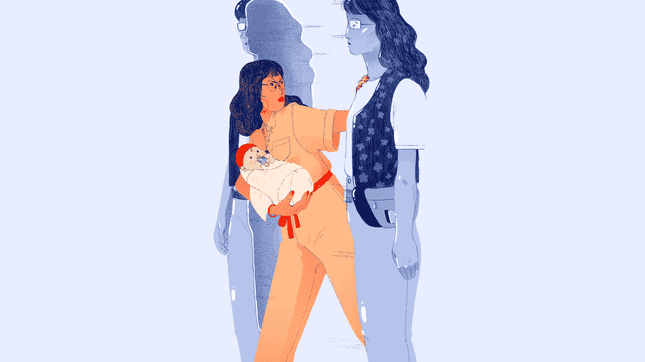

Image: Chelsea Beck/GO Media

“You dress cute for a mom,” an acquaintance recently told me. She was giving me the once over after a group of us had just finished lunch. Maybe she was surprised that my shirt wasn’t stained with spit-up. Or that my boots weren’t worn through the heel. I wasn’t sure. But the phrase “for a mom” hammered in my head.

“You know I’m… not just a mom, right?” I responded. She smiled, unsure what I meant and not concerned enough to ask.

I’ve heard variations of this comment since having a kid four years ago. “Looking good, mom.” “Ooh, I like your mom style.” “You’re, like, cool for a mom, yeah?” I guess I could be flattered that I’ve exceeded the depressing standard we have for mothers. But that in and of itself is the problem. There is the fact that I am being seen as a mother first and foremost, even though in the lunch situation I was with a group of women discussing our careers. Then there is the assumption that the norm is for women to abandon the tastes, autonomy, and esteem they have built over decades for some kind of disheveled uniform when they have a child. And this is in the progressive, self-absorbed, mind-your-own-business chaos of New York City. This is in 2019, when the mothers of young children are millennials and normie-hating Gen Xers.

Feminism is rather behind when it comes to parenting: There is talk about the fight for maternal healthcare and paid paternity leave. There is a surplus of unhappy mom essays, but our image of what a mother often remains remarkably one-dimensional.

When someone says “mom style,” what usually comes to mind is clothing that is comfortable and mindless—sweats, a loose tee for breastfeeding access, sneakers for playground runs—with variations that are designer (Golden Goose) or on a budget (Target). These are indeed basics that moms (and dads and non-binary parents and non-parents) wear. New mothers’ bodies are sore and extra and not necessarily trying to touch too much fabric. There is also something to be said about getting older and giving less of a shit about dressing up for others.

But parents aren’t new parents forever. Just like non-parents, they don’t run errands all day. They are people with multifaceted lives who also happen to have time-sucking responsibilities called children.

To be fair, mom jeans did recently have a cool moment in American culture. But even in that high-waisted, roomy-in-the-thigh concession was a snicker against the odds. The mention of “mom style” or clothes that look “mom” are usually the butt of a joke, and not one with much levity: They’re traditionally unflattering, a hint outdated. They’re for fading into the background. It’s the rare type of fashion where the point is for women to be invisible.

mom jeans did recently have a cool moment in American culture. But even in that high-waisted, roomy-in-the-thigh concession was a snicker against the odds

That isn’t to say there aren’t numerous blogs written about mom style or so-called mommy blogs that discuss style. But many are tips about how to embrace or jazz up the uniform. Influencer moms—even the hip and young—often put the hurdle of motherhood at the center of their content (breastfeeding problems, staying fit) or shill for traditional family goods (diapers, Disney trips). Readers and followers arrive with the understanding that the baseline of motherhood looks blah, maybe even miserable. At best, moms can embellish it up with a fun statement necklace and a sensible sandal.

“With ‘mom style,’ you’re starting from this preconceived notion of what a mom is, which in the U.S. is mostly a middle-aged, middle-class, educated white woman, so it’s already skewed toward one very narrow definition,” says Amy Westervelt, author of Forget Having It All: How America Messed Up Motherhood—and How to Fix It. She says this goes hand in hand with the expectation that a mom isn’t supposed to care about herself because “if she does, that’s selfish and taking away from her kids.”

Nothing quite embodies or perpetuates this archetype more than “mom style” trend pieces. Take a recent story in the New York Times Style section that devoted 1,500 words to white, well-to-do Park Slope moms and their $300 comfort clogs, women who are depicted as more of a mama-bear tribe than people who covet a certain material item. Before rolling our eyes at the subjects themselves, though, be warned they were set up to be gawked at like zoo animals. By being defined foremost by motherhood and rounded up by neighborhood, they are not being framed as individuals. They are being treated as a homogenous category of children-havers to be studied in a condescending tone. Look at this species! They’re all the same!

At least mom style has evolved from the conservative, dainty June Cleaver look. A time when women supposedly spent their days dusting in circle skirts and floral dresses that buttoned up to the throat. Well, not so fast. Moms still can’t be too sexy, either. Whether wearing a champagne glass on her ass or nothing at all, Kim Kardashian and other celebrities have been called out time and time again for not toning it down since having children. There remains a certain tasteful standard of what a stylish mom is supposed to look like. Even though it doesn’t align with her own ideas of what’s fashionable or cool, Westervelt says, a stylish mom usually “wears very expensive clothes, or is a J. Crew white sorority chick all grown up.”

When I casually asked a sampling of mothers what their gut reaction was to “mom style,” I received a lot of references to this Saturday Night Live sketch about mom jeans “cut generously to fit a mom’s body.” A few mentioned brands marketed to mothers like Lululemon. But mostly, I received groans and shrugs. It was a label that meant something specific but didn’t apply to their reality.

“Mom style” is really just a projection of the person using that term. Whatever imagery mom style conjures is likely linked to how we were raised to see women. It begins with our mothers.

I had the great fortune to grow up in Hawaii, where moms (aka women, humans) come in all shapes, colors, and sizes. When I think back to my friends’ mothers, there was the healer-hippie mom who loved linen capris and Birkenstocks, the immigrant mom who owned a jewelry store and was always dressed in a designer suit, and the young bartender mom whose off-the-shoulder tops her daughter would borrow. My own mother could have been the poster woman for ’80s fashion, with her hot pink geometric earrings, belted jumpsuits, and canvas bag filled with student book reports. When I look at photos of who she was before she had me—all sundresses and giant sunglasses—and who she was in her thirties and beyond, I still see the same confident, put-together woman.

It is why I never thought I was supposed to give up or change who I was when I became a mother. After I had my kid, my “style” was a source of comfort. Not that I dress in anything spectacular or high fashion; my clothes are just a reflection of my tastes: sexy butch, low-key goth, a fitted tee with patent leather Docs. Maybe I couldn’t fit into my pre-pregnancy jeans right away, maybe I was even stressed out about it, but I could fix my hair, draw a clean cat-eye, layer my necklaces, and feel like my old self, not just like a milk factory. It reminded me that even though my life had changed tremendously, I still was who I had always been.

Whatever imagery mom style conjures is likely linked to how we were raised to see women. It begins with our mothers

Obviously, I am not an anomaly. But some are doing the honorable work of shaking up the straight, white soccer mom standard through influence and visibility. And many say how they viewed motherhood started with the examples their own mothers had set.

Ruby Medina, founder of the L.A Mamacitas network for entrepreneur mothers in Southern California, says she too never thought she was supposed to look like a different person once she had kids. A 36-year-old Latina with two young daughters, she grew up in East Los Angeles with a mother who dressed up every day to run a hair salon.

“All the women that I would see in my mom’s salon were businesswomen, and I heard their conversations and it wasn’t just about kids. So that was instilled in me,” Medina says. “You still have your own personality.”

Medina says after she had kids, her style changed to being comfier, but it’s still what it has always been—edgy, androgynous. She says she rarely hears disparaging comments about her “mom style” because she is often surrounded by other mothers and they don’t talk like that. Her own mother still shops at Forever 21. Those who believe moms are “boring,” she says, might be thinking of their own mothers.

LaTonya Yvette, stylist and author of Woman of Color, has garnered 59,000 followers on Instagram not just because she dresses cool and her kids are cute (both of which are true), but because her pics also show her as a woman working, playing, and simply hanging out. Like most people, what she wears is based on what she’s doing: writing her book from home enabled more practical clothing, speaking engagements bring out the bright, flowy dresses. “Like anything, categorizing style, friends, or work into ‘mom groups’ is fraught,” she says. “It limits the imagination and style capabilities that women have whether they have children or not.”

She credits her mother, aunt, and grandmother for her fashion sense and confidence. “I saw my mother wake up and get dressed every single day, and I know as a kid that inspired me,” LaTonya says. “And I often think of those memories as my children run at my feet while I get ready in the morning.”

In what is perhaps a promising shift for not just “mom fashion” but fashion in general, Ebony and Denise of Team2Moms, who share their lives as LGBTQ parents on YouTube, are now ambassadors for H&M. This signals that mothers of all races and sexualities are being seen simply as women who wear clothes. “Our vision for why we started Team2Moms was to give a different representation to the world the types of families that are out there and celebrate those differences, and the uniqueness of those differences, and that there isn’t just one type,” Ebony says.

While Ebony and Denise tackle issues particular to raising kids in an interracial, LGBTQ relationship—like discussing how to talk to their oldest child about her sperm donor—they also just banter about their pet peeves, look at photos of their younger selves with their daughter, and play hilarious games like “Mom vs. wife: Who knows me better?”

Ebony says that growing up with a mother who held court as the matriarch of the family set the tone for the mothers they are today. She made motherhood seem less boxed in by certain roles or images. “Seeing the different challenges that [our mothers] faced from when we were kids till now, so much we have learned from them has made the transition for me and Denise much easier to be moms because we had such great examples and teachers before us,” she says.

Even if your mom wasn’t necessarily your style inspiration, if she helped you embrace your individuality, it likely reflects how you see yourself and other women. Westervelt says the iconic film Working Girl was a huge fashion inspiration to her in the fourth grade, and she wore suits with massive shoulder pads well into middle school. “My mom totally enabled this,” Westervelt says, “and I don’t know where she found so many little tiny power suits, but she bought them.”

While our moms may have been our first examples of what a woman should be, that isn’t to say our mothers and all mothers before them need to be held accountable for our culture’s crappy views of motherhood. They too were victims of centuries of compounded oppression in which motherhood has been used to guilt women against expressing their own autonomy, to look a certain way, to put others’ desires before their own. Our moms likely did the best they could with the circumstances they had to operate in and the views they had ingested.

I don’t know where she found so many little tiny power suits, but she bought them

For women like Medina, LaTonya, and myself, we were fortunate to grow up believing women with children can be complex in fascinating ways: They can have careers and relationships and laugh and enjoy themselves; they can also struggle and lose jobs and survive divorce. And then through it all, they can put on a pair of hot pants that makes them feel fun and flirty, while their kids bear witness.

But even if we too have paved our own way as mothers, that doesn’t mean we aren’t affected by the messaging that all moms are supposed to be the same. LaTonya says, “I am Black, young, and curvy. So immediately, as a woman and mother, I am categorized as XYZ when I show my skin or accent my own curves.” Ebony adds that people make assumptions about Denise for her masculine appearance and whether that makes her a “dad.”

“Looking good for a mom” has little to do with my clothes, and much more to do with the fact that it validates the shift I noticed in how others treated me once I had a kid: Whether I’m making a work presentation or running into an old friend at a bar, what people often see first is that I’m a mother, and if we have internalized that mothers are uninteresting and miserable, then it is a greater uphill battle to be taken seriously as a woman with ideas, creativity, or relevance. Or even just to be seen as an engaging human being.

American culture has a hard time understanding that personhood and parenthood can coexist. It’s not one or the other. “The everyday culture push of mothers to be covered, socially acceptable, not sexy, or at times, overly sexy to appease the patriarchy, doesn’t shift the cultural conversation on it,” says LaTonya. “We truly have to be unwilling to give an F, and do what we so desire.”

Like with most things, the way forward is obvious: reckon with unconscious biases, be more inclusive and less stereotypical when it comes to addressing a large swath of the population. Seek out and demand stories and imagery beyond cis, straight, white women in a maternal embrace or frazzled distress. Look at different historical perspectives on motherhood and push for more education and programming that doesn’t just capture moms in the home or behind the stroller but out in the world living their fucking lives.

But while we wait for mom style to evolve from a one-size-fits-all, we can also just stop using “mom” as a synonym for frumpy, dumpy, and to be pitied. We could bury the term mom style once and for all. Dig it a grave—and if it makes you feel freer, throw in your No. 6 clogs and Golden Gooses, too—and leave all the expectations and assumptions to rot.

Jessica Machado is the identities editor at the Daily Dot. You can follow her on Twitter.