It's Not a Clinic, It's a Caste System

Latest

Illustration: Jim Cooke

Because I cover healthcare, and because I work for a website concerned with all the ways people try to separate women from their money, I’m often directed to clinics that say they are revolutionizing basic care. Friends and strangers send me links to Instagram ads, portholes into identically extravagant offices. The waiting rooms are plush mid-century modern, the exam rooms an assortment of delicate monochromes washed in halos of light. There is usually a jungle of plants somewhere in the frame. This week, it was Tend, the dentist’s office that is miraculously also a “studio” and a “dental wellness brand,” where patients brush with Italian Amarelli licorice toothpaste and arrive to find their favorite HBO dramas pre-loaded on a screen. For its expansion it brought in $36 million late last year. A few months ago it was Parsley Health, the functional medicine startup that operates outside the indignities of the insurance system. “Primary care is broken,” according to its founder, and the solution, as rendered by Parsley, is a whole-body approach that includes microbiome and genetics testing. (Supplements, rather than medications, are encouraged but not typically included in the membership fee.)

For those who desire a more overt technological flex in their healthcare journey, there is Forward, another subscription-model primary care doctor where membership grants access to a whole-body biometric scanner and patients view an interactive double of their body during visits. Women have Tia, the members-only gynecologist, or Maven, the virtual prenatal clinic that proudly labels itself “insurance free,” or any of the plush fertility startups Wall Street salivates over as they gaze at market predictions that curve steeply North. At the outer limits, there is the baffling monolith The Well, a private “wellness club” with a dizzying array of offerings within its white-washed walls, including Chinese medicine, energy healing, and $850 consultations with a licensed MD.

Most of these places are trying to replicate, or at least latch on to, the massive success of One Medical, a membership-based primary care franchise that operates nearly 80 locations and went public last week with a valuation of over $1.5 billion, a modest sum given its projected success. Unlike similar startups treating local populations or Medicare patients, One Medical has become the industry’s blueprint, a fantastically valuable company that can also say it is “fixing” healthcare with a straight face. (Scooping up the segment of a $3.5 trillion industry that has decent insurance and extra cash lying around is generally understood to be lucrative as hell.)

It’s basic care—a check-up, a pap smear, a flu shot, a referral—but, unlike the rest of the medical landscape, it’s good.

As these clinics are generally careful to remind prospective patients, membership won’t replace an insurance policy. Primary care providers are the gatekeepers, the first point of contact, but they can’t pay for your prescriptions or cover a visit to a specialist if something goes seriously wrong. What these companies can do is purport to revitalize the healthcare “space” by cutting down hospital visits and encouraging preventative care. Mostly they do this by taking membership fees or operating on a strictly cash basis, which in turn guarantees a particularly expansive medical experience: hour-long conferences with a doctor, individualized wellness plans, and whatever additional perks white-collar professionals believe they deserve. It’s basic care—a check-up, a pap smear, a flu shot, a referral—but, unlike the rest of the medical landscape, it’s good. It’s same day appointments and doctors available 24/7 and someone in-house to help you navigate your insurance claims. It’s access to the latest technologies, stress-relief workshops, and more often than not, sparkling water if you happen to have to wait. In its IPO filing, One Medical followed in the footsteps of Peloton and Lululemon and described its brand as one that traded in “delight.”

Many of these offices lean on the language of whole-body unity and wellness, a tactic incubated and perfected by brands hoping to mine a specific kind of emptiness women have been conditioned to feel. It’s the ideal vocabulary for companies repackaging the most basic form of healthcare as a luxury good: These are doctor’s offices that talk about “restoring” health instead of treating it, practicing in “studios” rather than offices. Forward, founded by former employees of Google and Uber, refers to its patients as members: “Patients,” its CEO has said, “feels a little paternalistic to me.” It’s the corporate double-speak of industrious thirty-somethings and Silicon Valley investors in the process of convincing themselves the problem of American healthcare is atmospheric, a matter of seamless user experience and a few more potted plants.

These are doctor’s offices that talk about “restoring” health instead of treating it, practicing in “studios” rather than offices.

On a practical level, these businesses can be faintly ridiculous. Imagine the hubris required to “reinvent” a system considered the worst in the world among its peers, and to do it with flavored toothpaste and CBD seltzer on tap. If you take it all together, though, it’s more than a punchline about excess. Companies like Goldman Sachs already contract doctors to treat their employees’ hip ailments and “investment-banker necks” from the glass tower of the office. And Apple and Amazon both launched standalone healthcare initiatives for their more highly paid employees in recent years.

AC Wellness for Apple employees in the Bay Area offers a “concierge-like” experience with nutritionists and exercise coaches. Amazon Care, limited at the moment, notably, to people working in the company’s Seattle offices rather than those who are routinely injured and sometimes killed on the job, does house calls for non-acute needs. Google’s venture arm Alphabet invests significantly in One Medical; Google employees, along with the workers for two other companies unnamed in its IPO filing, make up more than a third of One Medical’s customer base.

As with many of the institutions created by tech money, for all of the optimism conferred in the idea of “fixing” the building blocks of healthcare, these are companies building parallel universes alongside the existing system. With their sharp angles and glass walls, these clinics look like they were built on one of those utopic garden planets where the enlightened beings of sci-fi television instantly cure ailments and generate new limbs. But as in fiction, in our adjacent but Earth-bound reality, for every utopia there is an over-extracted universe full of garbage where pretty much everyone else has to live.

The amount a patient is asked to pay for the privilege of delightful basic care varies wildly. Assuming a member of One Medical—or their employer—is already shelling out for decent insurance, and that no one in their family contracts an expensive illness or gets hit by a truck, they might get away with the occasional co-pay, plus the $200 yearly fee. But even in an industry known for being gluttonous, some practices promising deeper care in exchange for cash can be absurd: A few months ago, I spoke to a woman who saw doctors at Parsley for just under two years, desperate for help with a debilitating chronic illness. She estimates that between the $150 monthly charge (billed, at the time, biannually) and the additional supplements, tests, and treatments, she was out ten grand.

“Concierge care,” by now a far less trendy way to describe these kinds of doctors’ offices, has been around since the ‘90s, and in its less transparent corners can contain truly grotesque displays of wealth. An unlisted doctor in New York charges up to $80,000 a year for a family in exchange for VIP access to specialists and detailed quarterly health assessments. He refers to himself as an “asset manager” for their organs and limbs. Gold Cards at UCLA, available for purchase, gets a person to the front of the line for an MRI. “Direct primary care” practices, where clinics cut out the middleman (the insurance company; the state) charge a flat fee for basic care. Both are supplemental to basic coverage, in that they cover primary care and nothing else. According to an NPR report out last month, one in five wealthy people participate in some form of this model: “I think as long as you favor capitalism,” a hospital executive who spends $133 a month for a better doctor told the outlet, “it’s perfectly fair.”

We’re living through the quiet development of a sector designed to let people opt out and level significantly up.

Over the last decade, these practices have multiplied and democratized, if you can really call it that, bringing fees down anywhere from $60 to $300 a month. No one knows how many there are, precisely, but most everyone agrees they’re on the rise, even as over the same period Americans with commercial insurance are visiting their primary care doctor far less because co-pays have increased. These offices have cousins in all manner of institutions eager to escape the grim realities of the healthcare system as it exists and profit off of Americans with the means and will to escape. Crossover Health and Equal Health charge extra fees to employers to provide employees with next-level basic care. A handful of hospitals, including the Cleveland Clinic in Florida and Mass General, have programs where patients spend a few thousand dollars a year for customized wellness plans and direct phone lines for their MDs. Hudson Yards, the swanky development in Manhattan, includes the option to access an exclusive in-house concierge clinic when a person purchases a home, the median price of which is about $4.5 million. As presidential candidates argue over prescription drug prices and who deserves care, we’re living through the quiet development of a sector designed to let people who can already afford our expensive, unwieldy system to opt out and level significantly up.

A direct primary care office is a good bet politically, both in this moment and for the foreseeable future. In the immediate term, industry-specific lobbying organizations have made inroads with the current administration, which values above all the freedom of dollars and choice: The problem, articulated by Health and Human Services, is that consumers simply don’t have enough information to compare clinicians and bargain shop. But cutting out the middle-man is in itself a good insurance policy against whatever reforms the future might bring: In any scenario, there will be people willing to spend significantly on the healthcare industry’s version of a first class flight.

Of larger concern, at least from these companies’ perspective, is the likelihood that they will hire all the good doctors and have no way to continue to expand. Working in concierge care is, by most accounts, more desirable than laboring in the trenches of a traditional clinic: Doctors see fewer patients and get paid just as well, if not more. In its IPO filing, One Medical noted that it may be difficult in the future to attract qualified professionals, an inadvertent nod to the critical lack of primary care doctors that already exist: In Texas, for instance, at last count 35 counties had no physician of any kind. Taken to its most extreme conclusion, the company’s concern foreshadows a future in which the country’s good clinicians have mostly given up on our broken system and defected to prettier offices with better perks.

In all likelihood, it simply allows statistically healthier people to enjoy even better health.

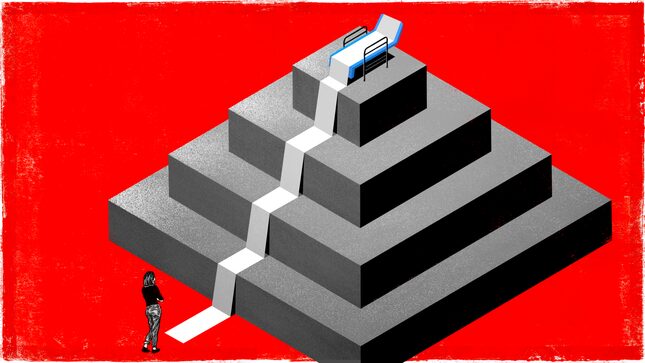

This is obviously a simplification, but if you wanted summarize the stratification of access to the American healthcare system it would look something like this: People without insurance, or near-useless disaster coverage, would be on the bottom, right under Medicaid patients. Above them might be people with employer-sponsored healthcare, or a state-approved partner with insurance, or the means to purchase an insurance policy themselves. Concierge medicine, no matter how allegedly accessible or transparent, adds another stratosphere to the equation, allowing those with disposable income to purchase the promise of wellness. In all likelihood, it simply allows statistically healthier people to enjoy even better health. Of course it’s an attractive sector for the tech industry and its obsession with optimization and time-saving tech—and to people for whom holistic and high-touch care is as much about lifestyle as a matter of life or death.

In their efforts to make the doctor’s office more enchanting, some medical “studios” build Instagram-friendly walls where patients can arrange themselves, the ultimate colonization of medicine by a wellness industrial complex bent on collapsing the metrics of attractiveness and health. Forward, which costs $1,800 a year, leans heavily on the diagnostic tools it built, including a glowing full-body scanner that uses “red light spectroscopy” to measure various facets of the heart. Parsley centers a suite of tests—genetics, comprehensive hormone analysis—that will get to the root cause of symptoms from brain fog to asthma to bad skin. These are doubtlessly committed doctors, practicing medicine in good faith, but it’s hard not to notice that as 45,000 people die every year from lack of adequate care, the market has developed the attitude that people with resources are sick in more interesting or obscure ways than everyone else.

As with any innovation pointed at the deadly disorders of American healthcare, the failures these companies say they are addressing are well-documented, if not the definitive cause of the overall disease. Healthcare spending—as of 2017, nearly one-fifth of this country’s GDP—is now broadly understood to be exacerbated by preventable illnesses and unhealthy patterns that fester for years. Poor eating habits and lack of exercise bloom into chronic diabetes; habitual neglect turns into a fatal respiratory disease. An estimated 84 million Americans live without access to primary care; researchers expect the United States to lose an additional 30,000 of those doctors in the next five years as they retire and are not replaced.

Small practices and family doctor’s offices have become subsumed by the forces of an insurance system that counts care in increments of billable procedures: Some medical schools, weighted towards research, train more grant magnets than omnivorous professionals. The system heaps high salaries on specialists and surgeons, neglecting the small-scale doctors who focus on patients’ more mundane needs. A reform movement emphasizing doctor-patient relationships has, improbably, been consistent across administrations: The spectre of indigent patients stumbling into emergency rooms to undergo expensive, preventable procedures appears to have haunted Obama as he pitched the ACA, and this month, the department of Health and Human Services implemented a long-promised set of incentives rewarding doctors not for procedures but for their patients’ overall health.

Atul Gawande, the surgeon and New Yorker staffer whose writing on healthcare costs deeply influenced Obama-era policies, grappled with this system in a 2017 magazine piece. It was an act of contrition, a meditation on the limits of “heroic” medical miracles like the ones he had risen to prominence performing: “We can give up an antiquated set of priorities and shift our focus from rescue medicine to lifelong incremental care,” he concluded, “or we can leave millions of people to suffer and die.” A year later, Gawande was appointed to lead Haven, the secretive non-profit healthcare alliance between Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JP Morgan, the engine of which is generally understood to be corporate dissatisfaction with how much workers cost to be kept alive.

As one might expect, the question of who benefits from such comprehensive wellness offerings is complex. Some have argued preventative care doesn’t bring down costs at all, and the two prominent university research programs testing whether patients coded as “high-risk” benefit from advanced primary care are at odds. This January, MIT released the discouraging results of a four-year study, finding that matching low-income patients with extensive healthcare resources had no significant impact on their hospitalization rates; a similar experiment out of Chicago has reported similar populations were re-hospitalized about 20% less when provided with a dedicated doctor and attentive clinical staff. How strange then that MDVIP, a concierge doctor prefiguring One Medical, says that for people paying $2,000 a year it can reduce hospitalization rates between 70% and 90%

The tech industry thrives where there is an opportunity to invoke a bit of behavioral economics and repackage a concept for young, technologically savvy people open to spending a little more money every month. These clinics are leaning on the same research developed to address the problem of low-income people dying in expensive and preventable ways: they’re just applying it to a population statistically far more likely to see results. One Medical pitches itself as a way for companies to keep their professional-class employees out of the hospital. On its website, Parsley invokes the CDC’s findings that one in five Americans suffers from a chronic disease. But Parsley isn’t really talking about something like diabetes, which afflicts almost 1 in 10 Americans: The company buys Google ads to show up when a person searches for SIBO, a relatively rare intestinal disorder associated with autoimmune disease and chronic fatigue.

Last year, I got a few complaints from One Medical patients about what felt, to them, like a scam: The yearly fee the company charges for its services, the so-called “concierge” part of the concierge medicine, was an optional part of the deal. This is because it’s legally risky, if not impossible, to charge a membership fee for services covered by insurance: Most of these clinics have to split up their businesses somewhat to accommodate this, applying membership fees to the perks rather than the actual care, or else operating completely “insurance free.”

If you don’t shell out the extra $200 at One Medical, you can technically see one of its doctors, as I found when I called up a representative. You just won’t get what she called the “full technology stack,” the 24/7 access to doctors, the “wellness and lifestyle offerings,” the “value adds.” In our short conversation, the woman on the other end of the phone said “seamless” four times. Picking up on what I’m sure was my obvious skepticism, she closed by telling me she really believed One Medical was doing public good and elevating care.

But the most insidious thing is how easily these clinics present simple, adequate health as a luxury good, a well-earned treat.

I have no doubt that was the way she felt. When I did a story on a membership gynecology and “well-woman” clinic in New York, I was essentially told something similar—that the existence of companies like this would make it so that someday, more people would have access to delightful, thoughtful care. And come on: It’s only a few hundred bucks a year, less than the average millennial spends on takeout or streaming services or coffee. It’s not like they’re a pharmaceutical company, or an insurance giant refusing to pay out for necessary care.

The market-driven argument, in which better clinics drive competition, is a familiar one, but I’d argue healthcare is more like housing than a superior latte: You can build a whole lot of luxury condos or even modest single-family homes and yet homelessness, against all odds, refuses to disappear. But the most insidious thing that strikes me is how easily and often these clinics present simple, adequate health as a luxury good, a well-earned treat. Access to primary care is ostensibly the building block of the system: it’s the ability to see a doctor, to get a referral, to seek advice when you feel ill. This entire ecosystem, which appears to be getting bigger every day, was bankrolled and built by people who have concluded the only way to reform the system is to build another one where the simplest form of healthcare is a saleable and aspirational experience, not a service. And definitely not a right.

A previous version of this story erroneously stated Hudson Yards, the lavish mixed-use neighborhood invented by a development company, was in Brooklyn, which has several of its its own lavish mixed-use neighborhood invented by a development company. It is in Manhattan. Jezebel regrets the error.