I Turned to Extraction for Joyful Violence and a Sexy Chris, But Alas It Was Disturbing

EntertainmentMovies

There is a certain kind of action movie that I find to be deeply comforting, a category of entertainment I’ve nicknamed the “president protection plot” in my mind. Presidents, however, play a minimal role in these movies, besides hanging out and being generally benign and good and worthy of life. Instead, the film centers around a person practiced at sanctioned killing. This person, say a secret service agent or a bodyguard, must protect another more important person, often a head of state, under enormously difficult conditions. The bad guys in these movies are always very bad, whether they’re North Korean mercenaries (Olympus Has Fallen), foreign weapons dealers (London Has Fallen) or American weapons dealers (Angel Has Fallen), to cover a single trilogy, and they too are very good at their jobs.

They don’t just shoot off a sniper shot—they enact carefully orchestrated plans to overthrow the government, barrel through the gates onto the White House lawn, invade Air Force One, blow up the Capitol, and simultaneously execute 20 heads of state. The handsome white man bodyguard (they are without exception handsome white men) must conquer an entire army single-handedly, in a song-and-dance routine that conveniently helps him work through some personal problems. Though these movies involve a very specific set of circumstances, they are ubiquitous—presumably built by an algorithm in a national lab so as to be plentiful. In times of great duress, I have no problem finding a different one to watch every night, as I have now for close to a month, searching “action movies like Patriot Games,” and slotting in another murder-movie-but-with-heart into my queue.

It’s obvious what the narrative provides: a simple sense of right and wrong, a government that is generally trustworthy at its core—at least once you murder off all the secret agents—and the basic primal thrill of watching a human perform impossible physical feats with the assurance, improbably, that all will end well. So when Jezebel’s culture editor asked someone to watch Extraction, a Netflix film starring Chris Hemsworth—a different, more Australian Chris than the bodyguard from White House Down, but a famous one, nonetheless—as an independent mercenary hired to rescue Ovi, the kidnapped child of a powerful drug lord, I was confident in my ability to find joy in the promised “gut punch escapism.” Adrenaline, after all, is a limitless delight. Aficionados raved about an 11-minute-long single-cut chase scene choreographed like a ballet. Twitter promised wit and a level of self-awareness: Hemsworth’s character, a man named Tyler Rake, cracks a man’s head open with a garden tool, the rake.

I can’t tell you much about the rake goring scene, because if it does happen, I missed it—likely while pausing the movie every 10 minutes to brace myself for the next excruciating stretch. There is very little entertainment to be found in a movie that delights in somber acts of violence. The limit, I discovered, does exist.

Spoilers ahead.

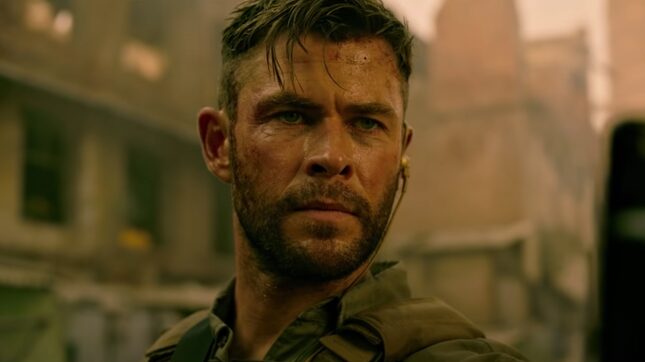

Extraction begins with Hemsworth on a bridge, bruised, bloody, and potentially dying. The corpses of what appears to be an entire army surround him. It’s unclear where the movie will go after killing the star off in the first few minutes. Soon we move to a flashback, with setup. The bridge, it is explained, is Hemsworth’s route out of Dhakar, where he’s traveled to rescue Ovi, the teenage son of a drug lord, who has been kidnapped by another drug lord bent on revenge and humiliation. Ovi’s father, however, is in prison and having fallen on hard times and is unable to pay a team of professional mercenaries to rescue his son.He is, however, powerful enough to frighten his surrogates with enough death and destruction that his lead henchman, terrified, invents a scheme to hire Hemsworth’s crew and screw them out of their final payment—which seems like it should work out well! Thus Hemsworth’s journey to the bridge is, in fact, a moral undertaking: will he rescue the child and forgo his paycheck? Or assure his own safety and ditch him for safety outside of city limits. The bridge is a metaphor… for something.

Here are some things that happen in Extraction: A teenager is shot in the forehead. A small child is thrown to his death off a roof. Another teenager is forced to cut off his own fingers. (“I recommend the left [hand], so you can still hold a gun,” his captor says.) Rocket launchers are launched into cars. Bullets are shot into the necks of people holding rocket launchers. After being run over by a truck, a rescuer snaps his broken nose back into place, releasing a gush of blood into his mouth. Hemsworth shoots and stabs and sends bullets into the fleshy space between protective helmets and bullet-proof vests—he hits this spot so frequently that by the time the aforementioned 11-and-a-half-minute single-shot sequence happens, I was no longer surprised by his precision.

At one point, one of Hemsworth’s more treacherous colleagues suggests that he murder the child and escape intact. “The best thing you could do right now is… put a bullet in his brain,” he implores. The setup implies that the suggestion is bad, but it’s not entirely illogical. Two armies have been dispatched—one to protect Ovi, one to return him to his kidnapper—and both are filled with individuals acting out of fear for punishment or violence either drug lord might enact if they fail at their task. By the hundredth or thousandth murder, watching Hemsworth nonchalantly hit an artery at close range for a satisfying little explosion, I began to wonder if the child’s life was really worth the stakes. In Extraction, violence exists much as it does in life, triggered from afar by powerful people, enacted by those too fearful to not comply. It’s hard to find any escapism in something so close to home.